History of genetic engineering

Important advances included the discovery of restriction enzymes and DNA ligases, the ability to design plasmids and technologies like polymerase chain reaction and sequencing.

[3] Human directed genetic manipulation was occurring much earlier, beginning with the domestication of plants and animals through artificial selection.

The dog is believed to be the first animal domesticated, possibly arising from a common ancestor of the grey wolf,[2] with archeological evidence dating to about 12,000 BC.

[6] The first evidence of plant domestication comes from emmer and einkorn wheat found in pre-Pottery Neolithic A villages in Southwest Asia dated about 10,500 to 10,100 BC.

[7] The Fertile Crescent of Western Asia, Egypt, and India were sites of the earliest planned sowing and harvesting of plants that had previously been gathered in the wild.

Independent development of agriculture occurred in northern and southern China, Africa's Sahel, New Guinea and several regions of the Americas.

[12]: 25 Common characteristics that were bred into domesticated plants include grains that did not shatter to allow easier harvesting, uniform ripening, shorter lifespans that translate to faster growing, loss of toxic compounds, and productivity.

[16] In 1889 Hugo de Vries came up with the name "(pan)gene" after postulating that particles are responsible for inheritance of characteristics[17] and the term "genetics" was coined by William Bateson in 1905.

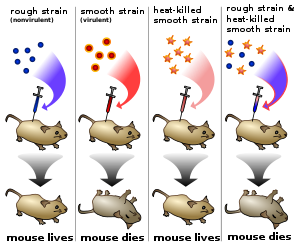

[18] In 1928 Frederick Griffith proved the existence of a "transforming principle" involved in inheritance, which Avery, MacLeod and McCarty later (1944) identified as DNA.

Edward Lawrie Tatum and George Wells Beadle developed the central dogma that genes code for proteins in 1941.

In 1970 Hamilton Smith's lab discovered restriction enzymes that allowed DNA to be cut at specific places and separated out on an electrophoresis gel.

Frederick Sanger developed a method for sequencing DNA in 1977, greatly increasing the genetic information available to researchers.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR), developed by Kary Mullis in 1983, allowed small sections of DNA to be amplified and aided identification and isolation of genetic material.

Artificial competence was induced in Escherichia coli in 1970 when Morton Mandel and Akiko Higa showed that it could take up bacteriophage λ after treatment with calcium chloride solution (CaCl2).

[27] Herbert Boyer and Stanley Norman Cohen took Berg's work a step further and introduced recombinant DNA into a bacterial cell.

Together they found a restriction enzyme that cut the pSC101 plasmid at a single point and were able to insert and ligate a gene that conferred resistance to the kanamycin antibiotic into the gap.

Cohen had previously devised a method where bacteria could be induced to take up a plasmid and using this they were able to create a bacterium that survived in the presence of the kanamycin.

They repeated experiments showing that other genes could be expressed in bacteria, including one from the toad Xenopus laevis, the first cross kingdom transformation.

[31][32] Jaenisch was studying mammalian cells infected with simian virus 40 (SV40) when he happened to read a paper from Beatrice Mintz describing the generation of chimera mice.

[38] The Asilomar recommendations were voluntary, but in 1976 the US National Institute of Health (NIH) formed a recombinant DNA advisory committee.

[39] This was followed by other regulatory offices (the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA), effectively making all recombinant DNA research tightly regulated in the US.

[42] In the late 1980s and early 1990s, guidance on assessing the safety of genetically engineered plants and food emerged from organizations including the FAO and WHO.

[48] The ability to insert, alter or remove genes in model organisms allowed scientists to study the genetic elements of human diseases.

[60] As not all plant cells were susceptible to infection by A. tumefaciens other methods were developed, including electroporation, micro-injection[61] and particle bombardment with a gene gun (invented in 1987).

[67] The first animal to synthesise transgenic proteins in their milk were mice,[68] engineered to produce human tissue plasminogen activator.

Chinese labs used it to create a fungus-resistant wheat and boost rice yields, while a U.K. group used it to tweak a barley gene that could help produce drought-resistant varieties.

When used to precisely remove material from DNA without adding genes from other species, the result is not subject the lengthy and expensive regulatory process associated with GMOs.

[77] In 1983 a biotech company, Advanced Genetic Sciences (AGS) applied for U.S. government authorization to perform field tests with the ice-minus strain of P. syringae to protect crops from frost, but environmental groups and protestors delayed the field tests for four years with legal challenges.

[92] The first genetically modified animal to be commercialised was the GloFish, a Zebra fish with a fluorescent gene added that allows it to glow in the dark under ultraviolet light.

[96] Opposition continued following controversial and publicly debated papers published in 1999 and 2013 that claimed negative environmental and health impacts from genetically modified crops.