List of regicides of Charles I

[2] At the end of the four-day trial, 67 commissioners stood to signify that they judged Charles I had "traitorously and maliciously levied war against the present Parliament and the people therein represented".

General George Monck—who had fought for the King until his capture, but had joined Cromwell during the Interregnum—brought an army down from his base in Scotland and restored order; he arranged for elections to be held in early 1660.

He began discussions with Charles II who made the Declaration of Breda—on Monck's advice—which offered reconciliation, forgiveness, and moderation in religious and political matters.

[2][9] According to Howard Nenner, writing for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Charles would probably have been content with a smaller number to be punished, but Parliament took a strong line.

[2] Of those who were listed to receive punishment, 24 had already died, including Cromwell, John Bradshaw, the judge who was president of the court, and Henry Ireton.

Five days later he writes, "I saw the limbs of some of our new traitors set upon Aldersgate, which was a sad sight to see; and a bloody week this and the last have been, there being ten hanged, drawn, and quartered.

Twenty-one of those under threat fled Britain, mostly settling in the Netherlands or Switzerland, although some were captured and returned to England, or murdered by Royalist sympathisers.

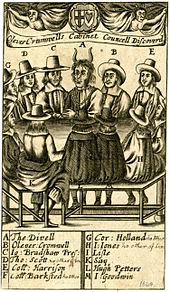

[13][14] In the order in which they signed the death warrant, the Commissioners were: The following Commissioners sat on one or more days at the trial but did not sign the death warrant: Under the Scottish Act of indemnity and oblivion (9 September 1662), as with the English act most were pardoned and their crimes forgotten, however, a few members of the previous regime were tried and found guilty of treason (for more details see General pardon and exceptions in Scotland):