Literature of Laos

[3] As an inland crossroads of Southeast Asia the political history of Laos has been complicated by frequent warfare and colonial conquests by European and regional rivals.

Lao literature spans a wide range of genres including religious, philosophy, prose, epic or lyric poetry, histories, traditional law and customs, folklore, astrology, rituals, grammar and lexicography, dramas, romances, comedies, and non-fiction.

[8] Most works of Lao literature have been handed down through continuous copying and have survived in the form of palm-leaf manuscripts, which were traditionally stored in wooden caskets and kept in the libraries of Buddhist monasteries.

By the end of the nineteenth century the French had forced Siam to cede the areas on the east bank of the Mekong River, and had roughly established the borders of modern Laos.

Subjects were primarily religious or historical in nature, but also included epic poems, law, customs, astrology, numerology, as well as traditional medicine and healing.

The Lord of Heaven (Phaya Thaen) at this point in the epic saves the divine children and the queens by constructing a castle in the sky for them to live.

The six brothers, not wanting to lose face in the eyes of their father push Sin Xay, the golden-tusked elephant and snail off a cliff and tell the king's sister that they had tragically drowned.

Despite the changes, major thematic elements and wording remained consistent, so the epic is one of the only descriptions of life in Southeast Asia among indigenous peoples during the Tai migrations.

The tale of the Toad King (Phya Khankhaak) and the nithan or love poem Phadaeng Nang Ai are extremely popular literary works and are read or sung as part of the Rocket Festival (Boun Bang Fai; Lao: ບຸນບັ້ງໄຟ,) celebrations each year.

History was related using san (poetry) which was intended to be sung or performed, and phongsavadan (chronicles) which were meant to be read aloud during festivals and important occasions.

The Lao frequently wrote origin legends (nithan a-thi bay hed) for the people, places, and cultural relics which were part of their society.

The Buddha images were symbols of royal and religious authority, and their stories combined folklore with animist traditions to become powerful palladiums of the monarchy and kingdoms of Lan Xang and Laos.

The Isan region, although historically within the Lan Xang mandala, was more accessible for the growing power of a nationalist Siam where the population could be taxed or brought into the corvee system of labor.

The dominance of Siam during the nineteenth century left the Lao unable to remain politically independent, and the infighting among the kingdoms of Vientiane, Luang Prabang and Champassak was bitterly resented among the common people.

In one of the most enigmatic and controversial Lao epics, the Leup Pha Sun expresses the author's sadness that he cannot speak freely of his country while he tries to cope with tumultuous relationship between Lan Xang and Siam using both romantic and religious language and imagery.

Throughout the areas of what are today southeast Myanmar, the Xipsongpanna in China, north and northeast Thailand, northwest Vietnam, and Laos it was common for monks, texts and even complete libraries to move between monasteries.

Generally, the most popular texts include blessings used in ritual ceremonies (animasa); blessings used for protection (paritta); instructions used for lay or religious ceremonies (xalong); non-canonical stories from the life of the Buddha (jataka); commentary on Tipitaka (atthakatha); ritual rules or instructions for monks and nuns (kammavaca and vinaya pitaka); local epics and legends (e.g. Xiang Miang, Sin Xay, and Thao Hung Thao Cheuang); summary treatises on Theravadist doctrine (Visuddhimagga and Mangaladipani); grammar handbooks (excerpts from the Padarūpasiddhi and Kaccāyanavyākarana); and relic, image and temple histories (tamnan).Jataka tales are morality stories which recall previous incarnations of the Buddha before he was able to reach enlightenment.

The story recalls the past life of a compassionate prince, Vessantara, who gives away everything he owns, including his children, thereby displaying the virtue of perfect charity.

The category can apply to almost any narrative form of expression, and includes many myths, customs, popular beliefs, riddles, jokes, and common depictions of everyday life.

Folk traditions include the protector spirits of the Mekong River, the nāga which take a serpentine form and are popular motifs in Lao art, weaving and folklore.

The stories involve the protagonist Xiang Miang, who is portrayed as a boy and novice monk, and his efforts to outwit the king or abbot in both humorous and morally instructive ways.

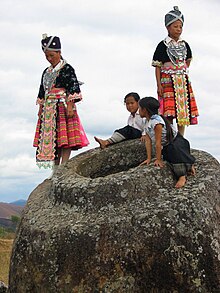

Stories from the Mon-Khmer, Blang, Lamet, Khmu, Akha, Tibeto-Burmese, Tai-Rau, and Hmong-Mien create unique myths, legends, laws, customs, beliefs and identities which have been passed down largely through oral tradition.

In the Isan region, the fascist policies of Field Marshal Phibun, sought to forcibly assimilate the ethnic minorities of Thailand into the Central Thai identity.

The ultimate goal was an attempt to absorb the territories of Laos (as well as the Malay in the South, and the remaining traditions of the Tai Yuan, of Lanna) into a reunified Thailand, within the borders of the former Siam.

When Paris fell to the Axis powers in 1940, the momentary weakness of the Vichy Government, forced France to permit the Empire of Japan to establish a military presence in Indochina.

However the rifts between the political factions were deep and split along both ideological and personal lines among the Lao royal family, and would later give rise to the Laotian Civil War.

All of these groups and transitions are creating a broad spectrum of uniquely Lao literary voices, which are reemerging with a frequency that had long been dormant since the classical era of Lan Xang.

Academics like George Coedes, Henri Parmentier, and Louis Finot working in the late 1910s and 1920s produced the first in depth cultural materials on Laos since the explorations of Auguste Pavie in the 1870s.

Maha Sila Viravong did extensive work on the early classics identifying the major masterpieces of Lao storytelling and producing one of the first popular histories of Lan Xang.

The Toyota Foundation in conjunction with the Lao Ministry of Information and Culture began an initiative to catalogue over 300,000 phuk (palm-leaf books) in over 800 monasteries.