Little Orphan Annie

Little Orphan Annie displays literary kinship with the picaresque novel in its seemingly endless string of episodic and unrelated adventures in the life of a character who wanders like an innocent vagabond through a corrupt world.

She makes it clear that she does not like Annie and tries to send her back to "the Home", but one of her society friends catches her in the act, and immediately, to her disgust, she changes her mind.

By the 1930s, during the Great Depression, the formula was tweaked: Daddy Warbucks lost his fortune due to a corrupt rival and briefly died from despair at the 1944 re-election of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Oliver "Daddy" Warbucks first appears in a September 1924 strip and reveals a month later he was formerly a small machine shop owner who acquired his enormous wealth producing munitions during World War I.

Other major characters include Warbucks' right-hand men: Punjab, an eight-foot native of India, introduced in 1935, and the Asp, an inscrutably generalized East Asian, who first appeared in 1937.

After World War I, cartoonist Harold Gray joined the Chicago Tribune which, at that time, was being reworked by owner Joseph Medill Patterson into an important national journal.

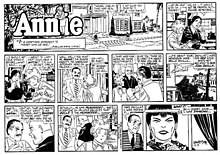

Gray's strips were consistently rejected by Patterson, but Little Orphan Annie was finally accepted and debuted in a test run on August 5, 1924, in the New York Daily News, a Tribune-owned tabloid.

A Fortune popularity poll in 1937 indicated Little Orphan Annie ranked number one and ahead of Popeye, Dick Tracy, Bringing Up Father, The Gumps, Blondie, Moon Mullins, Joe Palooka, Li'l Abner and Tillie the Toiler.

[citation needed] Starting January 4, 1931, Gray added a topper strip to the Little Orphan Annie Sunday page called Private Life Of...

[8] The Herald Dispatch of Huntington, West Virginia, stopped running Little Orphan Annie, printing a front-page editorial rebuking Gray's politics.

"[citation needed] As war clouds gathered, both the Chicago Tribune and the New York Daily News advocated neutrality; "Daddy" Warbucks, however, was gleefully manufacturing tanks, planes, and munitions.

Journalist James Edward Vlamos deplored the loss of fantasy, innocence, and humor in the "funnies", and took to task one of Gray's sequences about espionage, noting that the "fate of the nation" rested on "Annie's frail shoulders".

In his reply, Gray denied being a reformer, but pointed out that Annie was a friend to all, and his inclusion of a black character, was "merely a casual gesture toward a very large block of readers."

Following Roosevelt's death in April 1945, Gray resurrected Warbucks with the explanation that he had only been playing dead to thwart his enemies, and once again the billionaire began expounding the joys of capitalism.

[13] In the post-war years, Annie took on The Bomb, communism, teenage rebellion and a host of other social and political concerns, often provoking the enmity of clergymen, union leaders and others.

In 1956, a sequence about juvenile delinquency, drug addiction, switchblades, prostitutes, crooked cops, and the ties between teens and adult gangsters unleashed a firestorm of criticism; 30 newspapers cancelled the strip.

Early in 1974, David Lettick took the strip, but his Annie was drawn in an entirely different and more "cartoonish" style, leading to reader complaints, and he left after only three months.

Maeder's writing style also tended to make the stories feel like tongue-in-cheek adventures compared to the serious, heartfelt tales Gray and Starr favored.

"[18] The last strip was the culmination of a story arc where Annie was kidnapped from her hotel by a wanted war criminal from eastern Europe who checked in under a phony name with a fake passport.

Although Warbucks enlists the help of the FBI and Interpol to find her, by the end of the final strip he has begun to resign himself to the very strong possibility that Annie most likely will not be found alive.

A third appearance of Annie and her supporting cast in Dick Tracy's strip began on May 16, 2019, and involves both B-B Eyes' murder and doubts about the fate of Trixie.

[25] Little Orphan Annie was adapted to a 15-minute radio show that debuted on WGN Chicago in 1930 and went national on NBC's Blue Network beginning April 6, 1931.

Actresses who portrayed Miss Hannigan are Dorothy Loudon, Alice Ghostley, Betty Hutton, Ruth Kobart, Marcia Lewis, June Havoc, Nell Carter and Sally Struthers.

The 1982 version was directed by John Huston and starred Aileen Quinn as Annie, Albert Finney as Warbucks, Ann Reinking as his secretary Grace Farrell, and Carol Burnett as Miss Hannigan.

It starred Victor Garber, Alan Cumming, Audra McDonald and Kristin Chenoweth, with Oscar winner Kathy Bates as Miss Hannigan and newcomer Alicia Morton as Annie.

While its plot stuck closer to the original Broadway production, it also omitted "We'd Like to Thank You, Herbert Hoover", "Annie", "New Deal for Christmas", and a reprise of "Tomorrow."

[34][35] In medicine, "Orphan Annie eye" (empty or "ground glass") nuclei are a characteristic histological finding in papillary carcinoma of the thyroid gland.

[citation needed] "Little Orphan Melvin" appears in the ninth issue of Mad magazine by Harvey Kurtzman and Wally Wood, published 1952.

[citation needed] 1980s children's program You Can't Do That on Television parodied the character as "Little Orphan Andrea" in its "Adoption" episode, later banned.

[citation needed] The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles comics by Mirage Studios feature a fictional toy line named "Little Orphan Aliens".