Common periwinkle

This is of particular importance to evolutionary biology, as it may represent an opportunity to observe a transitional phase in the evolution of an organism.

[7] L. littorea is oviparous, reproducing annually with internal fertilization of egg capsules that are then shed directly into the sea, leading to a planktotrophic larval development time of four to seven weeks.

[8] Females lay 10,000 to 100,000 eggs contained in a corneous capsule from which pelagic larvae escape and eventually settle to the bottom.

[11] Common periwinkles are native to the northeastern coasts of the Atlantic Ocean, including northern Spain, France, Great Britain, Ireland, Scandinavia, and Russia.

Common periwinkles were introduced to the Atlantic coast of North America, possibly by rock ballast in the mid-19th century.

It has changed North Atlantic intertidal ecosystems via grazing activities, altering the distribution and abundance of algae on rocky shores and converting soft-sediment habitats to hard substrates, as well as competitively displacing native species.

[9][8] The common periwinkle is mainly found on rocky shores in the higher and middle intertidal zone.

[9] When exposed to either extreme cold or heat while climbing, a periwinkle will withdraw into its shell and start rolling, which may allow it to fall to the water.

Phlorotannins in the brown algae Fucus vesiculosus and Ascophyllum nodosum act as chemical defenses against L.

[19] The common periwinkle can act as a host for various parasites, including Renicola roscovita, Cryptocotyle lingua, Microphallus pygmaeus and Himasthla sp.

[20] Polydora ciliata has also been found to excavate burrows in the shell of the common periwinkle when the snail is mature (above 10 mm long).

Another hypothesis is that a mature snail has a change in the shell surface that makes it suitable for P. ciliata larvae to settle.

[23][full citation needed] It is still collected in quantity in Scotland, mostly for export to the Continent and also for local consumption.

[24][full citation needed] Periwinkles are usually picked off the rocks by hand or caught in a drag from a boat.

In accordance with their history as an ancient food source in Atlantic Europe, they are harvested and consumed in the Azores Islands by the Portuguese people, where they are usually called búzios, the generic name for sea snails.

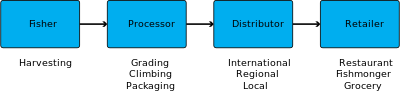

The true nature of the supply chain is usually more complex and opaque, with the potential for records of harvesting areas and date of catch to be falsified.

Commonly harvested in buckets by workers walking in the intertidal zone on low tide; other methods have been tried.

A report on the state of the periwinkle industry in Ireland suggests a maximum catch size in order to preserve the population[citation needed].

The processor buys in bulk from the collector, involving a possibly long transport route by land in a refrigerator truck or airplane, taking care to avoid temperatures below 0°C.

If fresh seawater is readily available, the periwinkles are first graded if possible, using a machine custom built for the purpose.

By harvesting the periwinkle during the summer and storing them with feed until December, not only should the grade have been increased, but the market value should be higher since supply is lower in the cold winter months.

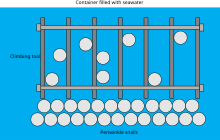

[26] Raising the common periwinkle has not been a focus due to its abundance in nature and relatively low price; however, there are potential benefits from aquaculture of this species, including a more controlled environment, easier harvesting, less damages from predators, as well as saving the natural population from commercial harvesting.

Holes in the box ensures that any water lost by the snails drains out, so that they remain in better condition for longer.