Litvaks

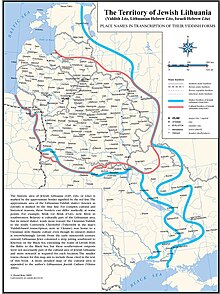

Litvaks (Yiddish: ליטװאַקעס) or Lita'im (Hebrew: לִיטָאִים) are Jews with roots in the territory of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania (covering present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, the northeastern Suwałki and Białystok regions of Poland, as well as adjacent areas of modern-day Russia and Ukraine).

[2][3][4][5] The term is sometimes used to cover all Haredi Jews who follow an Ashkenazi, non-Hasidic style of life and learning, whatever their ethnic background.

In modern Israel, Lita'im (Lithuanians) is often used for all Haredi Jews who are not Hasidim (and not Hardalim or Sephardic Haredim).

Both the words Litvishe and Lita'im are somewhat misleading, because there are also Hasidic Jews from greater Lithuania and many Litvaks who are not Haredim.

[15] Differences between the groups grew to the extent that in popular perception "Lithuanian" and "misnagged" became virtually interchangeable terms.

However, a sizable minority of Litvaks belong(ed) to Hasidic groups, including Chabad, Slonim, Karlin-Stolin, Karlin (Pinsk), Lechovitch, Amdur and Koidanov.

In theoretical Talmud study, the leading Lithuanian authorities were Chaim Soloveitchik and the Brisker school; rival approaches were those of the Mir and Telshe yeshivas.

In the 19th century, the Orthodox Ashkenazi residents of the Holy Land, broadly speaking, were divided into Hasidim and Perushim, who were Litvaks influenced by the Vilna Gaon.

Another reason for this broadening of the term is the fact that many of the leading Israeli Haredi yeshivas (outside the Hasidic camp) are successor bodies to the famous yeshivot of Lithuania, though their present-day members may or may not be descended from Lithuanian Jewry.

[citation needed] In 1388, they were granted a charter by Vytautas, under which they formed a class of freemen subject in all criminal cases directly to the jurisdiction of the grand duke and his official representatives, and in petty suits to the jurisdiction of local officials on an equal footing with the lesser nobles (szlachta), boyars, and other free citizens.

Its most characteristic feature is the pronunciation of the vowel holam as [ej] (as against Sephardic [oː], Germanic [au] and Polish [oj]).

[21] This difference is of course connected with the Hasidic/misnaged debate, Hasidism being considered the more emotional and spontaneous form of religious expression.

The Galitzianers were known for rich, heavily sweetened dishes in contrast to the plainer, more savory Litvisher versions, with the boundary known as the Gefilte Fish Line.