Misnagdim

Misnagdim (מתנגדים, "Opponents"; Sephardi pronunciation: Mitnagdim; singular misnaged / mitnaged) was a religious movement among the Jews of Eastern Europe which resisted the rise of Hasidism in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The most severe clashes between the factions took place in the latter third of the 18th century; the failure to contain Hasidism led the Misnagdim to develop distinct religious philosophies and communal institutions, which were not merely a perpetuation of the old status quo but often innovative.

Hasidism's founder was Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer (c. 1700–1760), known as the Baal Shem Tov ("master of a good name" usually applied to a saintly Jew who was also a wonder-worker), or simply by the acronym Besht (Hebrew: בעש"ט); he taught that man's relationship with God depended on immediate religious experience, in addition to knowledge and observance of the details of the Torah and Talmud.

The Hasidic leaders' inclination to rule in legal matters, binding for the whole community (as opposed to strictures voluntarily adopted by the few), based on mystical considerations, greatly angered the Misnagdim.

[5] On another, theoretical level, Chaim of Volozhin and his disciples did not share Hasidism's basic notion that man could grasp the immanence of God's presence in the created universe, thus being able to transcend ordinary reality and potentially infuse common actions with spiritual meaning.

In fact, however, a sizable minority of Greater Lithuanian Jews belong(ed) to Hasidic groups, including Chabad, Slonim, Karlin-Stolin (Pinsk), Amdur and Koidanov.

Most of the changes made by the Hasidim were the product of the Hasidic approach to Kabbalah, mainly as expressed by Isaac Luria (1534–1572) and his disciples, particularly Hayyim ben Joseph Vital (1543–1620).

Depending on how this idea was preached and interpreted, it could give rise to pantheism, universally acknowledged as heresy, or lead to immoral behavior, since elements of Kabbalah can be misconstrued to de-emphasize ritual and glorify sexual metaphors as a more profound means of grasping some inner hidden notions in the Torah based on the Jews' intimate relationship with God.

If God is present in everything, and if divinity is to be grasped in erotic terms, then—Misnagdim feared—Hasidim might feel justified in neglecting legal distinctions between the holy and the profane, and in engaging in inappropriate sexual activities.

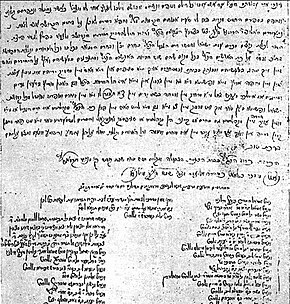

[7] In late 1772, after uniting the scholars of Brisk, Minsk and other Belarusian and Lithuanian communities, the Vilna Gaon then issued the first of many polemical letters against the nascent Hasidic movement, which was included in the anti-Hasidic anthology, Zemir aritsim ve-ḥarvot tsurim (1772).

In total, this was seen to be a radical departure from the Misnagdic norm of asceticism, scholarship, and stoic demeanor in worship and general conduct, and was viewed as a development that needed to be suppressed.

While many followers of this movement were observant, it was also used by the absolutist state to change Jewish education and culture, which both Misnagdim and Hasidim perceived as a greater threat to religion than they represented to each other.

Litvishe Jews largely identify with the Misnagdim, who "objected to what they saw as Hasidic denigration of Torah study and normative Jewish law in favor of undue emphasis on emotionality and religious fellowship as pathways to the Divine.