Livyatan

It is mainly known from the Pisco Formation of Peru during the Tortonian stage of the Miocene epoch, about 9.9–8.9 million years ago (mya); however, finds of isolated teeth from other locations such as Chile, Argentina, the United States (California), South Africa and Australia imply that either it or a close relative survived into the Pliocene, around 5 mya, and may have had a global presence.

Characteristically of raptorial sperm whales, Livyatan had functional, enamel-coated teeth on the upper and lower jaws, as well as several features suitable for hunting large prey.

Livyatan's total length has been estimated to be about 13.5–17.5 m (44–57 ft), almost similar to that of the modern sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), making it one of the largest predators known to have existed.

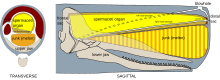

The spermaceti organ contained in that basin is thought to have been used in echolocation and communication, or for ramming prey and other sperm whales.

In November 2008, a partially preserved skull, as well as teeth and the lower jaw, belonging to L., the holotype specimen MUSM 1676, were discovered in the coastal desert of Peru in the sediments of the Pisco Formation, 35 km (22 mi) southwest of the city of Ica.

[1][2] Klaas Post, a researcher for the Natural History Museum Rotterdam in the Netherlands, stumbled across them on the final day of a field trip.

The species name melvillei is a reference to Herman Melville, author of the book Moby-Dick, which features a gigantic sperm whale as the main antagonist.

[8] During the late 2010s and 2020s, fossils of large isolated sperm whale teeth were reported from various Miocene and Pliocene localities mostly along the Southern Hemisphere.

[1] In 2018, palaeontologists led by David Sebastian Piazza, while revising the collections of the Bariloche Paleontological Museum and the Municipal Paleontological Museum of Lamarque, uncovered two incomplete sperm whale teeth cataloged as MML 882 and BAR-2601 that were recovered from the Saladar Member of the Gran Bajo del Gualicho Formation in the Río Negro Province of Argentina, a deposit that dates between around 20–14 mya.

[9][15] In 2019, palaeontologist Romala Govender reported the discovery of two large sperm whale teeth from Pliocene deposits near the Hondeklip Bay village of Namaqualand in South Africa.

[10] In 2023, graduate student Kristin Watmore and paleontologist Donald Prothero reported in a preprint a giant sperm whale tooth identified as cf.

At the area where part of the tooth broke off revealed layers of cementum and dentin of thickness within the known range of L. melvillei teeth.

OCPC 3125/66099 represented the first evidence that either Livyatan or Livyatan-like whales were not restricted to the Southern Hemisphere and likely indicated a possibly global distribution of the cetaceans.

Lambert and colleagues estimated the body length of Livyatan using Zygophyseter and modern sperm whales as a guide.

The condyloid process, which connects the lower jaw to the skull, was located near the bottom of the mandible like other sperm whales.

Unlike other sperm whales with functional teeth in the upper jaw, none of the tooth roots were entirely present in the premaxilla portion of the snout, being at least partially in the maxilla.

The supracranial basin was the deepest and widest over the braincase, and, unlike other raptorial sperm whales, it did not overhang the eye socket.

The large teeth of the raptorial sperm whales either evolved once in the group with a basilosaurid-like common ancestor, or independently in Livyatan.

The large temporal fossa in the skull of raptorial sperm whales is thought to a plesiomorphic feature, that is, a trait inherited from a common ancestor.

[1][8] It has also been suggested that the raptorial sperm whales should be placed into the subfamily Hoplocetinae, alongside the genera Diaphorocetus, Idiorophus, Scaldicetus and Hoplocetus, which are known from the Miocene to the lower Pliocene.

[1][8][22] †Eudelphis †Zygophyseter †Brygmophyseter †Acrophyseter †Livyatan †'Aulophyseter' rionegrensis †Orycterocetus †Idiorophus †Physeterula †Idiophyseter Physeter †Aulophyseter †Placoziphius †Diaphorocetus †Aprixokogia Kogia †Praekogia †Scaphokogia †Thalassocetus Livyatan was an apex predator, and probably had a profound impact on the structuring of Miocene marine communities.

It probably also preyed upon sharks, seals, dolphins and other large marine vertebrates, occupying a niche similar to the modern killer whale (Orcinus orca).

It was contemporaneous with and occupied the same region as the otodontid shark O. megalodon, which was likely also an apex predator, implying competition over their similar food sources.

[27] The supracranial basin in its head suggests that Livyatan had a large spermaceti organ, a series of oil and wax reservoirs separated by connective tissue.

[1][3][8] An alternate theory is that sperm whales, including Livyatan, can alter the temperature of the wax in the organ to aid in buoyancy.

However, additional isolated large sperm whale teeth from other locations including California, Australia, Argentina and South Africa have been identified as a species or possible close relative of Livyatan.

However, collecting bias was another explanation given the apparent rarity and poor fossil record of Livyatan,[9] now supported by the Northern Hemisphere occurrence in California.

[11] The holotype of L. melvillei is from the Tortonian stage of the Upper Miocene 9.9–8.9 mya in the Pisco Formation of Peru, which is known for its well-preserved assemblage of marine vertebrates.

The Hondeklip Bay locality enjoys a rich heritage of marine fossils, whose diversity may have been thanks to the initiation of the Benguela Upwelling during the late Miocene, which likely provided large populations of phytoplankton traveling the cold nutrient-rich waters.

[1][3][4][5] Their extinction also coincides with the emergence of the orcas as well as large predatory globicephaline dolphins, possibly acting as an additional stressor to their already collapsing niche.