Local food

"[3] For example, local food initiatives often promote sustainable and organic farming practices, although these are not explicitly related to the geographic proximity of producer and consumer.

[3] Using metrics such as these, a Vermont-based farm and food advocacy organization, Strolling of the Heifers, publishes the annual Locavore Index, a ranking of the 50 U.S. states plus Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia.

[13] A recent study led by economist Miguel Gomez found that the supermarket supply chain often did much better in terms of food miles and fuel consumption for each pound compared to farmers markets.

[15] Launched in 2009, North Carolina's 10% local food campaign is aimed at stimulating economic development, creating jobs and promoting the state's agricultural offerings.

[20] Locavores seek out farmers close to where they live, and this significantly reduces the amount of travel time required for food to get from farm to table.

[21] The combination of local farming techniques and short travel distances makes the food consumed more likely to be fresh, an added benefit.

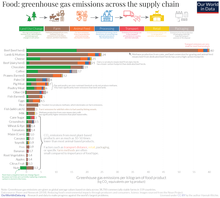

[7][23] Local foods require less energy to store and transport, possibly reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

For example, the concept that fewer "food miles" translates to a more sustainable meal has not been supported by major scientific studies.

According to a study conducted at Lincoln University in New Zealand: "As a concept, food miles has gained some traction with the popular press and certain groups overseas.

[30] Studies have shown that the amount of gasses saved by local transportation while existing, does not have a significant enough impact to consider it a benefit.

[31] The only[citation needed] study to date that directly focuses on whether or not a local diet is more helpful in reducing greenhouse gases was conducted by Christopher L. Weber and H. Scott Matthews at Carnegie-Mellon.

They concluded that "dietary shift can be a more effective means of lowering an average household's food-related climate footprint than 'buying local'".

[32] An Our World In Data post makes the same point, that food choice is overwhelmingly more important than emissions from transport.

[36] The study concludes that "a shift towards plant-based foods must be coupled with more locally produced items, mainly in affluent countries".

[38] Adrian Williams of Cranfield University in England found that free range and organic raised chickens have a 20% greater impact on global warming than chickens raised in factory farm conditions, and organic egg production had a 14% higher impact on the climate than factory farm egg production.

These latter criticisms combine with deeper concerns of food safety, cited on the lines of the historical pattern of economic or food safety inefficiencies of subsistence farming which form the topic of the book The Locavore's Dilemma by geographer Pierre Desrochers and public policy scholar Hiroko Shimizu.