John Locke

[17] Internationally, Locke's political-legal principles continue to have a profound influence on the theory and practice of limited representative government and the protection of basic rights and freedoms under the rule of law.

[18] Locke's philosophy of mind is often cited as the origin of modern conceptions of personal identity and the psychology of self, figuring prominently in the work of later philosophers, such as Rousseau, David Hume, and Immanuel Kant.

Locke's father, also named John, was an attorney who served as clerk to the Justices of the Peace in Chew Magna,[22] and as a captain of cavalry for the Parliamentarian forces during the early part of the English Civil War.

Through his friend Richard Lower, whom he knew from the Westminster School, Locke was introduced to medicine and the experimental philosophy being pursued at other universities and in the Royal Society, of which he eventually became a member.

Following Shaftesbury's fall from favour in 1675, Locke spent some time travelling across France as a tutor and medical attendant to Caleb Banks.

[30] The work is now viewed as a more general argument against absolute monarchy (particularly as espoused by Robert Filmer and Thomas Hobbes) and for individual consent as the basis of political legitimacy.

Although Locke was associated with the influential Whigs, his ideas about natural rights and government are considered quite revolutionary for that period in English history.

[31] The philosopher and novelist Rebecca Newberger Goldstein argues that during his five years in Holland, Locke chose his friends "from among the same freethinking members of dissenting Protestant groups as Spinoza's small group of loyal confidants [Baruch Spinoza had died in 1677], Locke almost certainly met men in Amsterdam who spoke of the ideas of that renegade Jew who ... insisted on identifying himself through his religion of reason alone."

After a lengthy period of poor health,[33] Locke died on 28 October 1704, and is buried in the churchyard of All Saints' Church in High Laver, near Harlow in Essex, where he had lived in the household of Sir Francis Masham since 1691.

However, with the rise of American resistance to British taxation, the Second Treatise of Government gained a new readership; it was frequently cited in the debates in both America and Britain.

Michael Zuckert has argued that Locke launched liberalism by tempering Hobbesian absolutism and clearly separating the realms of Church and State.

I consider them as the three greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception, and as having laid the foundation of those superstructures which have been raised in the Physical and Moral sciences.Locke's influence may have been even more profound in the realm of epistemology.

At the time, Locke's recognition of two types of ideas, simple and complex—and, more importantly, their interaction through association—inspired other philosophers, such as David Hume and George Berkeley, to revise and expand this theory and apply it to explain how humans gain knowledge in the physical world.

[47][48][49][50] Baptist theologian Roger Williams founded the colony of Rhode Island in 1636, where he combined a democratic constitution with unlimited religious freedom.

His tract, The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience (1644), which was widely read in the mother country, was a passionate plea for absolute religious freedom and the total separation of church and state.

[51] Freedom of conscience had had high priority on the theological, philosophical, and political agenda, as Martin Luther refused to recant his beliefs before the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire at Worms in 1521, unless he would be proved false by the Bible.

[58] Brewer likewise argues that Locke actively worked to undermine slavery in Virginia while heading a Board of Trade created by William of Orange following the Glorious Revolution.

He specifically attacked colonial policy granting land to slave owners and encouraged the baptism and Christian education of the children of enslaved Africans to undercut a major justification of slavery—that they were heathens who possessed no rights.

[63]: 198 Most scholars trace the phrase "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness" in the American Declaration of Independence to Locke's theory of rights,[64] although other origins have been suggested.

In his view, the introduction of money marked the culmination of this process, making possible the unlimited accumulation of property without causing waste through spoilage.

Locke stresses that inequality has come about by tacit agreement on the use of money, not by the social contract establishing civil society or the law of land regulating property.

He argues the brokers—the middlemen—whose activities enlarge the monetary circuit and whose profits eat into the earnings of labourers and landholders, have a negative influence on both personal and the public economy to which they supposedly contribute.

[73] Locke states in his Second Treatise that nature on its own provides little of value to society, implying that the labour expended in the creation of goods gives them their value.

[80] He argues that the "associations of ideas" that one makes when young are more important than those made later because they are the foundation of the self; they are, put differently, what first mark the tabula rasa.

In his Essay, in which both these concepts are introduced, Locke warns, for example, against letting "a foolish maid" convince a child that "goblins and sprites" are associated with the night, for "darkness shall ever afterwards bring with it those frightful ideas, and they shall be so joined, that he can no more bear the one than the other".

It also led to the development of psychology and other new disciplines with David Hartley's attempt to discover a biological mechanism for associationism in his Observations on Man (1749).

[97][98][99] Locke derived the fundamental concepts of his political theory from biblical texts, in particular from Genesis 1 and 2 (creation), the Decalogue, the Golden Rule, the teachings of Jesus, and the letters of Paul the Apostle.

According to John Harrison and Peter Laslett, the largest genres in Locke's library were theology (23.8% of books), medicine (11.1%), politics and law (10.7%), and classical literature (10.1%).

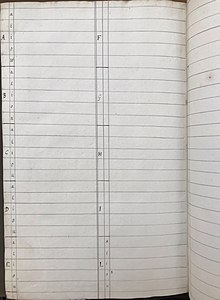

"[114] In an unpublished essay "Of Study," Locke argued that a notebook should work like a "chest-of-drawers" for organising information, which would be a "great help to the memory and means to avoid confusion in our thoughts.

[117] Another way Locke personalised his notebooks was by devising his own method of creating indexes using a grid system and Latin keywords.