Kingdom of the Lombards

A reduced Regnum Italiae, a heritage of the Lombards, continued to exist for centuries as one of the constituent kingdoms of the Holy Roman Empire, roughly corresponding to the territory of the former Langobardia Maior.

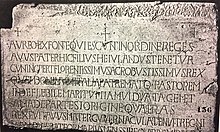

The earliest Lombard law code, the Edictum Rothari, may allude to the use of seal rings, but it is not until the reign of Ratchis that they became an integral part of royal administration, when the king required their use on passports.

Although the Byzantine Empire eventually prevailed, the triumph proved to be a pyrrhic victory, as all these factors caused the population of the Italian Peninsula to crash, leaving the conquered territories severely underpopulated and impoverished.

In the spring of 568 the Lombards, led by King Alboin, moved from Pannonia and quickly overwhelmed the small Byzantine army left by Narses to guard Italy.

The duchy, established in the Roman town of Forum Iulii (modern-day Cividale del Friuli), constantly fought with the Slavic population across the Gorizia border.

[7] In 572, after the capitulation of Pavia and its elevation to the royal capital, King Alboin was assassinated in a conspiracy in Verona plotted by his wife Rosamund and her lover, the noble Helmichis, in league with some Gepid and Lombard warriors.

Helmichis and Rosamund's attempt to usurp power in place of the assassinated Alboin, however, gained little support from Lombard duchies, and they were forced to flee together to the Byzantine territory before getting married in Ravenna.

[9] After ten years of interregnum, the need for a strong centralised monarchy was clear even to the most independent of the dukes; Franks and Byzantines pressed and the Lombards could no longer afford so fluid a power structure, useful only to make forays in search of plunder.

Then the king, in a move that would influence the fate of the kingdom for more than a century, turned to the traditional enemies of the Franks, the Bavarii, to marry a princess, Theodelinda, from the Lethings dynasty.

The period of Autari marked, according to Paul the Deacon, the attainment of the first internal stability in the Lombard kingdom: Erat hoc mirabile in regno Langobardorum: nulla erat violentia, nullae struebantur insidiae; nemo aliquem iniuste angariabat, nemo spoliabat; non erant furta, non latrocinia; unusquisque quo libebat securus sine timoreThere was a miracle in the kingdom of the Lombards: there was no violence, no insidious plot; no others unjustly oppressed, no depredations; there were no thefts, there were no robberies, where everyone went where they wanted, safely and without fearAutari died in 590, probably due to poisoning in a palace plot and, according to the legend recorded by Paul the Deacon,[12] the succession to the throne was decided in a novel fashion.

[13] After a rebellion among some dukes in 594 was preempted, Agilulf and Theodelinda developed a policy of strengthening their hold on Italian territory, while securing their borders through peace treaties with France and the Avars.

In northern Italy Agilulf occupied, among other cities, Parma, Piacenza, Padova, Monselice, Este, Cremona and Mantua, but also to the south the duchies of Spoleto and Benevento, extending the Lombards' domains.

The new organisation of power, less linked to race and clan relations and more to land management, marked a milestone in the consolidation of the Lombard kingdom in Italy, which gradually lost the character of a pure military occupation and approached a more proper state model.

[13] The inclusion of the losers (the Romans) was an inevitable step, and Agilulf made some symbolic choices aimed at the same time at strengthening its power and gaining credit with people of Latin descent.

The rulers also endeavored to heal the Three Chapter schism (where the Patriarch of Aquileia had broken communion with Rome), maintained a direct relationship with Gregory the Great (preserved in correspondence between him and Theodelinda) and promote the establishment of monasteries, like the one founded by Saint Columbanus in Bobbio.

[17] Arioald (r. 626–636), who brought the capital back to Pavia, was troubled by these conflicts, as well as external threats; the King was able to withstand an attack of the Avars in Friuli, but could not limit the growing influence of the Franks in the kingdom.

[19] Internally, Rothari strengthened the central power at the expense of the duchies of Langobardia Maior, while in the south the Duke of Benevento, Arechi I (who in turn was expanding Lombard domains), also recognized the authority of the King of Pavia.

He favoured the integration of the different components of the kingdom, presenting an image modeled on that of his predecessor Rotari—wise legislator in adding new laws to the Edict, patron (building a church in Pavia dedicated to Saint Ambrose), and valiant warrior.

The dukes of Austria challenged the increasing "latinization" of customs, court practices, law and religion, which they believed accelerated the disintegration and loss of the Germanic identity of the Lombard people.

On two occasions, in Sardinia and in the region of Arles (where he had been called by his ally Charles Martel) he successfully fought Saracen pirates, enhancing his reputation as a Christian king.

His alliance with the Franks, crowned by a symbolic adoption of the young Pepin the Short, and with the Avars, on the eastern borders, allowed him to keep his hand relatively free in the Italian theater, but he soon clashed with the Byzantines and with the Papacy.

Closer relations with the papacy therefore had to wait for the outbreak of tensions caused by the worsening of the Byzantine tax, and the expedition in 724 conducted by the Exarch of Ravenna against Pope Gregory II.

Later on he exploited the disputes between the pope and Constantinople over iconoclasm (after the decree of Emperor Leo III the Isaurian of 726) to take possession of many cities of the Exarchate and of the Pentapolis, posing as the protector of Catholics.

Population growth led to fragmentation of funds, which increased the number of Lombards who fell below the poverty line, as evidenced by the laws aimed at alleviating their difficulties.

With the occupation of the stronghold of Ceccano, he was putting further pressure on the territories controlled by Pope Stephen II, while in Langobardia Minor he was able to impose his power on Spoleto and, indirectly, on Benevento.

Aistulf, perched in Pavia, had to accept a treaty that required the delivery of hostages and territorial concessions, but two years later resumed the war against the pope, who in turn called on the Franks.

He opposed Desiderius, who was put in charge of the Duchy of Tuscia by Aistulf and based in Lucca; he did not belong to the dynasty of Friuli, frowned upon by the pope and the Franks, and managed to get their support.

Desiderius, with a clever and discreet policy, gradually reasserted Lombard control over the territory by gaining favor with the Romans again, creating a network of monasteries ruled by Lombard aristocrats (his daughter Anselperga was named abbess of San Salvatore in Brescia), dealing with Pope Stephen II's successor, Pope Paul I, and recognizing the nominal domain on many areas truly in his power, such as reclaimed southern duchies.

Charles then called himself Gratia Dei rex Francorum et Langobardorum ("By the grace of God king of the Franks and the Lombards"), realizing a personal union of the two kingdoms.

The figure of Bertoldo/Berthold, a humble and clever farmer from Retorbido, who lived during the reign of Alboin (568-572), inspired many oral traditions throughout the Middle Ages and early modern period.

The Lombard Kingdom (Neustria, Austria and Tuscia) and the Lombard Duchies of Spoleto and Benevento