London, Brighton and South Coast Railway

The LB&SCR had the most direct routes from London to the south coast seaside resorts of Brighton, Eastbourne, Worthing, Littlehampton and Bognor Regis, and to the ports of Newhaven and Shoreham-by-Sea.

The LB&SCR was formed at the same time as the bursting of the railway mania investment bubble, and so it found raising capital for expansion extremely difficult during the first years of its operation, other than to complete those projects that were already in hand.

In 1849 the LB&SCR appointed a new and capable chairman, Samuel Laing, who negotiated a formal agreement with the SER that would resolve their difficulties for the time being and would define the territories of the two railways.

In 1853 the Direct Portsmouth Railway gained parliamentary authority to build a line from Godalming to Havant with the intention of the company selling itself either to the L&SWR or the LB&SCR.

This scheme would provide a far more direct route to Portsmouth but involved sharing the LB&SCR tracks for the five miles (8 km) between Havant and the joint line to Portsea.

The Crystal Palace became a major tourist attraction and the LB&SCR built a branch line from Sydenham to the new site, which was opened in June 1854, and enlarged London Bridge station to handle the additional traffic.

[13] Samuel Laing retired as chairman at the end of 1855 to pursue a political career, and was replaced by the merchant banker Leo Schuster, who had previously sold his 300-acre (120 ha) estate on Sydenham Hill to the new Crystal Palace Company.

The LC&DR was used from Victoria to Brixton, followed by new construction by the LB&SCR through Denmark Hill, and Peckham to the main line to London Bridge at South Bermondsey.

It also obtained powers for the Ouse Valley Railway, from the south of Balcombe and north of Haywards Heath on the Brighton main line to Uckfield and Hailsham; an extension to St Leonards was also approved in May 1865.

They reached a low point in 1863 when the SER produced a report for its shareholders outlining a long list of the difficulties between the two companies, and the reasons why they considered that the LB&SCR had broken the 1848 agreement.

[30] The report made clear that the LB&SCR had overextended itself with large capital projects sustained by profits from passengers, which suddenly declined as a result of the crisis.

Several country lines were losing money – most notably between Horsham and Guildford, East Grinstead and Tunbridge Wells, and Banstead and Epsom – and the LB&SCR was committed to building or acquiring others with equally poor prospects.

[33] For the next decade, projects were limited to additional spurs or junctions in London and Brighton to enhance the operation of the network, or small-scale ventures in conjunction with other railway companies.

This part of the line was owned by the SER, which (according to Acworth) gave its trains precedence through the junctions at Redhill,[44] but the LB&SCR paid an annual fee of £14,000 for its use.

Relations with the SER began to deteriorate once more and eventually both companies appointed Henry Oakley general manager of the Great Northern Railway as an independent assessor in 1889.

[28] However this did not solve the problem and an 1896 study of LB&SCR passenger services, by J. Pearson Pattinson described the 8+1⁄4 miles (13.3 km) of shared track between Redhill and Stoats Nest (Coulsdon) as being 'in a state of the utmost congestion, and detentions of the Brighton expresses, blocked by South Eastern stopping trains, are as constant as irritating.

[47] The line involved substantial civil engineering works including the excavation of new tunnels at Merstham and Redhill, cuttings, embankments and a covered way at Cane Hill Hospital.

[59] According to Bonavia, 'the Brighton was a highly individual line in its strengths and weaknesses, it was to experience drastic changes under Southern [Railway] management which older members of the staff would not always accept gracefully.

As originally envisaged the railway was a trunk route, conveying passengers (and to a lesser extent goods) between London, Croydon and the south coast, with relatively little traffic to and from stations in between.

[68] After 1870, the LB&SCR greatly encouraged commuters into London by reducing the prices of season tickets and introducing special workmen's trains for manual workers in that year.

On the Isle of Wight the LB&SCR and the L&SWR jointly took over the ferry service from Portsmouth and built new pier at Ryde with a short line to the station at St John's Road in 1880.

[74] The LB&SCR served important Horse racing tracks at Brighton, Epsom, Gatwick, Goodwood, Lewes, Lingfield and Plumpton, and Portsmouth Park (Farlington).

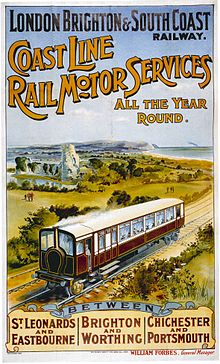

The L&SWR and the LB&SCR boards decided to investigate the use of steam powered railcars on the 1+1⁄4-mile (2 km) joint branch line between Fratton and East Southsea, in June 1903.

During the 1870s the pattern of goods services slowly began to change, leading to rapid growth in the 1890s, 'caused by the transport of raw materials and finished products of entirely new industries such as petroleum, cement, brick and tile manufacture, forestry and biscuit making.

[80] The bulk of its coal was brought in 800 long tons (810 t) trains from Acton yard on the Great Western Railway to Three Bridges for redistribution, and the LB&SCR kept two goods locomotives at the GWR Westbourne Park Depot for this purpose.

[86] There were also freight handling facilities at Battersea and Deptford Wharves, and New Cross in London and the railway constructed a marshalling yard to the south of Norwood Junction during the 1870s, extended in the early 1880s.

[90] Because of the nature of its traffic with a very large number of commuter journeys over relatively short distances, the railway was an obvious candidate for electrification, and had sought powers for suburban lines in 1903.

However the LB&SCR foresaw electrification of its main line, and ultimately to Portsmouth and Hastings, and therefore decided on a high-tension overhead supply system at 6,600 volts AC.

To do this the LB&SCR and the L&SWR formed the South Western and Brighton Railway Companies Steam Packet Service (SW&BRCSPS), which bought the operators.

[144] There were engine sheds at Battersea Park, Brighton, Bognor, Coulsdon, Croydon, Eastbourne, Epsom, Fratton (joint) Horsham, Littlehampton, Midhurst, New Cross, Newhaven, St Leonards, Three Bridges and Tunbridge Wells West.