London Necropolis Company

After an 1884 ruling that cremation was lawful in England the LNC also took advantage of its proximity to Woking Crematorium by providing transport for bodies and mourners on its railway line and after 1910 by interring ashes in a dedicated columbarium.

Links were formed with London's Muslim communities in an effort to encourage new burials, and a slow programme of clearing and restoring the derelict sections of the cemetery commenced.

[8] Despite this rapid growth in population, the amount of land set aside for use as graveyards remained unchanged at approximately 300 acres (0.47 sq mi; 1.2 km2),[8] spread across around 200 small sites.

[6] The difficulty of digging without disturbing existing graves led to bodies often simply being stacked on top of each other to fit the available space and covered with a layer of earth.

[13] A royal commission established in 1842 to investigate the problem concluded that London's burial grounds had become so overcrowded that it was impossible to dig a new grave without cutting through an existing one.

[24] An area of ground so distant as to be beyond any possible future extension of the Capital, sufficiently large to allow of its sub-division, not only into spacious distinct portions for the burial of each sect of the Christian Public, but also, if desired and deemed expedient, into as many separate compartments as there are parishes within London and its suburbs ... [and] a Mausoleum Church, with funeral chapels, private mausolea, vaults, and catacombs, large enough to contain, not only the thousands of coffins now lying within our numerous Metropolitan Churches, but also the coffins of all such dying in London, in this and future generations ... [A] grand and befitting gathering place for the metropolitan mortality of a mighty nation; a last home and bed of rest where the ashes of the high and low, the mighty and the weak, the learned and the ignorant, the wicked and the good, the idle and the industrious, in one vast co-mingled heap may repose together.While the negotiations over the state taking control of burials were ongoing, an alternative proposal was being drawn up by Richard Broun and Richard Sprye.

At a shareholders' meeting in August 1852 concerns were raised about the impact of funeral trains on normal traffic and of the secrecy in which negotiations between the LSWR and the promoters of the cemetery were conducted.

Drummond considered the scheme a front for land speculation, believing that the promoters only intended to use 400 acres (0.63 sq mi; 1.6 km2) for the cemetery and to develop the remaining 80% for building;[40][note 5] Mangles felt that the people of Woking were not being fairly compensated for the loss of their historic rights to use the common lands;[40] Ashley felt that the Metropolitan Interments Act 1850 had been a victory for the campaign to end private profiteering from death and that the new scheme would reverse these gains, and was also concerned about the health implications of diseased bodies being transported to and stored at the London terminus in large numbers while awaiting trains to Brookwood.

On 1 April 1851 a group of trustees led by Poor Law Commissioner William Voules purchased the rights to the scheme from Broun and Sprye for £20,000 (about £2.37 million in terms of 2025 consumer spending power) and, once the act of Parliament had been passed, founded the London Necropolis & National Mausoleum Company on their own without regard to their agreement with the original promoters.

[43] In early 1853, amid widespread allegations of voting irregularities and with the company unable to pay promised dividends, a number of the directors resigned, including Voules, and the remaining public confidence in the scheme collapsed.

[54] As well as the giant sequoias, the grounds were heavily planted with magnolia, rhododendron, coastal redwood, azalea, andromeda and monkeypuzzle, with the intention of creating perpetual greenery with large numbers of flowers and a strong floral scent throughout the cemetery.

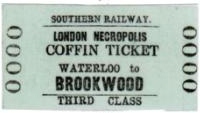

[59] On 13 November the first scheduled train left the new London Necropolis railway station for the cemetery, and the first burial (that of the stillborn twins of a Mr and Mrs Hore of Ewer Street, Borough) took place.

Yesterday, however, saw the practical embodiment of this idea ... A short distance beyond the Woking station, the country, without varying from its general character of sterility and hardness of outline, becomes gently undulating and offers features which, with some assistance from art, might be made more than pleasing.

[73][74] As the corpses brought to either of the reception-houses by the funeral tender are now taken each one its separate way, followed by its mourning-group, and by paths where privacy is unbroken, and none but soothing and religious influences around,—when amidst this scene, the clergyman or minister, unharassed by other duties, reads reverently the prayers for the dead,—when all which is this taking place tends to raise the dignity and self-respect of human nature, and create a sublime ideal of the great mystery of the grave, we perceive by contrast, more and more, what the evils of city and suburban burials have been, and what an educative process lies within even this portional one of their reformation ... Hither the wealthy and respectable are removing the remains of relatives from the graves and vaults of the metropolis, and hither the Nonconformists are bringing the long-interred dead from even the once-sacred place of Bunhill Fields ... but it is a law that moral and social advantages permeate as surely down through the strata of society as water finds its level.

[82] Although the LNC was never able to gain the domination of London's funeral industry for which its founders had hoped, it was very successful at targeting specialist groups of artisans and trades, to the extent that it became nicknamed "the Westminster Abbey of the middle classes".

[76] (After the relocation to the new London terminus in 1902, some funeral services would be held in a Chapelle Ardente on platform level, for those cases where mourners were unable to make the journey to Brookwood.

[94] The first major relocation took place in 1862, when the construction of Charing Cross railway station and the routes into it necessitated the demolition of the burial ground of Cure's College in Southwark.

[61] Concerns over the financial irregularities and the viability of the scheme had led to only 15,000 of the 25,000 LNC shares being sold, severely limiting the company's working capital and forcing it to take out large loans.

[97] Buying the land from Lord Onslow, compensating local residents for the loss of rights over Woking Common, draining and landscaping the portion to be used for the initial cemetery, and building the railway lines and stations were all expensive undertakings.

[84] It also allowed a ten-year window for the LNC to sell certain parts of the land bought from Lord Onslow which were not required for the cemetery, to provide a source of income.

[100][note 14] The crematorium was completed in 1879 but Richard Cross, the Home Secretary, bowed to strong protests from local residents and threatened to prosecute if any cremations were conducted.

[83] Tubbs was given a broad remit to "advance the company's interests", including buying and selling land, supervising the railway stations, advertising the cemetery and liaising with the LSWR.

[83] Tubbs established a masonry works and showroom near the centre of the cemetery, allowing the LNC to provide grave markers without the difficulty of shipping them from London,[113] and opened a LNC-owned nursery in the grounds for the sale of plants and wreaths.

[114] In around 1904 the masonry works was expanded and equipped with a siding from the railway branch line,[115] allowing the LNC to sell its gravestones and funerary art to cemeteries nationwide.

[2] By now the trees planted by the LNC in its early years of operations were mature, and Brookwood Cemetery was becoming a tourist attraction in its own right, often featuring in excursion guides of the 1920s and 1930s.

In the 1940s it bought out a number of other firms of funeral directors, particularly those catering for the expanding and prosperous suburbs of south west London within easy reach of Brookwood by road.

[138] In 1957 the Southern Region of British Railways considered allowing the LNC to sell discounted fares of 7s 6d (compared to the standard rate of 9s 4d) for return tickets for same-day travel from London to Brookwood and back.

[141] After Alliance Property's land sales, the London Necropolis Company had been reduced to Brookwood Cemetery itself and Frederick W. Paine, a Kingston-upon-Thames firm of funeral directors which had been bought by the LNC in 1947.

Frederick W. Paine was detached from the LNC, along with the specialist division overseeing the exhumation and relocation of existing burial grounds to allow property development on formerly consecrated sites.

[150] While it was never as successful as planned, the London Necropolis Company had a significant impact on the funeral industry, and the principles established by the LNC influenced the design of many other cemeteries worldwide.