London Ringways

The Ringway plans attracted vociferous opposition towards the end of the decade over the demolition of properties and noise pollution the roads would cause.

This ran further out from London than the North Circular and was planned to be around 70 miles (110 km) long, running from the A4 at Colnbrook to the A13 at Tilbury.

[7][8] Even in a war-ravaged city with large areas requiring reconstruction, the building of the two innermost rings, A and B, would have involved considerable demolition and upheaval.

The cost of the construction works needed to upgrade the existing London streets and roads to dual carriageway or motorway standards was considered significant; the A ring would have displaced 5,300 families.

Political pressure to build roads and improve vehicular traffic increased, which led to a revival of Abercrombie's plans.

The location of these lines produced a ring that was distinctly box-shaped, and Ringway 1 was unofficially called the London Motorway Box.

In contrast to earlier reports, it cautioned that road building would generate and increase traffic and cause environmental damage.

[18] At Blackheath, the road would have run in a deep-bored tunnel to avoid any impact on the local area, at an estimated cost of £38 million.

[29] In contrast, a public enquiry was held to review the GLDP in a climate of strong and vocal opposition from many of the London Borough councils and residents associations that would have seen motorways driven through their neighbourhoods.

[31] The GLC realised that the South Cross Route might be impractical to build, and looked instead at integrating public transport through a new park-and-ride scheme at Lewisham that would serve a new Fleet line on the London Underground.

[35] The project was submitted to the Conservative government for approval and, for a short period, it appeared that the GLC had made enough concessions for the scheme to proceed.

Part of the West Cross Route between North Kensington and Shepherd's Bush was opened by John Peyton and Michael Heseltine in 1970, simultaneously with Westway, to protests; some residents hung a huge banners with 'Get us out of this Hell – Rehouse Us Now' outside their windows and protesters disrupted the opening procession by driving a lorry the wrong way along the new road.

South of the river, Ringway 2 would have headed roughly toward the North Circular Road at Chiswick, though there was no definite proposed route.

In places, the road is a six-lane dual carriageway with grade separated junctions, while other parts remain at a much lower standard.

[52] At the western end of the North Circular Road a new section of motorway would have been constructed to take the route of Ringway 2 eastwards from the junction with the M4 at Gunnersbury along the course of the railway line through Chiswick to meet and cross the River Thames at Barnes.

[53] At its eastern end, Ringway 2 was planned to have crossed the River Thames at Gallions Reach in a new tunnel between Beckton and Thamesmead.

Next, heading west out of the London Borough of Greenwich, the motorway crossed to Baring Road (the A2212) near Grove Park station.

After this, there was a cut-and-cover tunnel underneath playing fields at Whitefoot Lane, followed by an elevated section over Bromley Road (A21).

[49] Ringway 2 took another elevated route crossing the railway by Goat House Bridge, before running in a cutting by South Norwood and Thornton Heath.

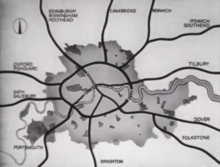

[69] The road was planned as a combination of motorway and all-purpose dual carriageway, connecting a number of towns around the capital including Tilbury, Epping, Hoddesdon, Hatfield, St Albans, Watford, Denham, Leatherhead and Sevenoaks.

With its elevated roadway on concrete pylons flying above the streets below at rooftop height, the Westway provides a good example of how much of Ringway 1 would have appeared had it been constructed.

However, these have been done in a piecemeal fashion so that the road varies in quality and capacity along its length and still has several unimproved single carriageway sections and awkward junctions.

The Wallington M23 Action Group campaigned for the motorway to be formally cancelled, as the inability to develop land along the line of the proposed M23 had led to planning blight in the area.

Some residents complained, saying the motorway should still be built, and that its terminus at Hooley caused a build up of traffic there, and contributed to congestion on other roads.

[82] The M23 to Streatham was briefly revived in 1985 by the GLC after the government had announced plans to spend £1.5 billion on trunk roads in London.

It was one of the few road proposals approved by the anti-car Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone, and included a dedicated lane for buses and cycles.

[citation needed] In 1979, the Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Transport, Kenneth Clarke, announced that the budget for developing London's road network would be cut from £500m to £170m.

[87] Upon becoming leader of the GLC in 1981, Ken Livingstone demanded an audit of all road schemes being worked on, including the remnants of Ringway plans, and cancelled many of them.

They did not have responsibility for maintaining any motorways, so the built parts of the Westway and West and East Cross Routes were downgraded to all-purpose roads.

[19] The website roads.org.uk, run by enthusiast Chris Marshall, has been praised for its level of detail in researching the Ringways, and cited as a definitive source of information.