Longship

Longships were a type of specialised Scandinavian warships that have a long history in Scandinavia, with their existence being archaeologically proven[1] and documented from at least the fourth century BC.

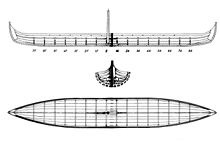

The ship's shallow draft allowed navigation in waters only one meter deep and permitted arbitrary beach landings, while its light weight enabled it to be carried over portages or used bottom-up for shelter in camps.

Dreki (singular, meaning 'dragon'),[13] was used for ships with thirty rowing benches and upwards[14] that are only known from historical sources, such as the 13th-century Göngu-Hrólfs saga.

The first dreki ship whose size was mentioned in the source was Olav Tryggvason's thirty-room Tranin, built at Nidaros circa 995.

The rounded sections gave maximum displacement for the lowest wetted surface area, similar to a modern narrow rowing skiff, so were very fast but had little carrying capacity.

It also had very rounded underwater sections but had more pronounced flare in the topsides, giving it more stability as well as keeping more water out of the boat at speed or in waves.

Its long, graceful, menacing head figure carved in the stern, such as the Oseburg ship, echoed the designs of its predecessors.

The plank above the turn of the bilge, the meginhufr, was about 37 mm (1.5 inches) thick on very long ships, but narrower to take the strain of the crossbeams.

Each overlap was stuffed with wool or animal hair or sometimes hemp soaked in pine tar to ensure water tightness.

At the bow and the stern builders were able to create hollow sections, or compound bends, at the waterline, making the entry point very fine.

Frames were placed close together, which is an enduring feature of thin planked ships, still used today on some lightweight wooden racing craft such as those designed by Bruce Farr.

In some ships the gap between the lower uneven futtock and the lapstrake planks was filled with a spacer block about 200 mm (8 inches) long.

[20] A drain plug hole about 25 mm (1 inch) was drilled in the garboard plank on one side to allow rain water drainage.

At the bow the forward upper futtock protruded about 400 mm (16 inches) above the sheerline and was carved to retain anchor or mooring lines.

This consisted of a 1.2-metre long (3.9 ft) wooden handle with a T crossbar at the upper end, fitted with a broad chisel-like cutting edge of iron.

The lower part of the side stay consisted of ropes looped under the end of a knee of upper futtock which had a hole underneath.

The lower part of the stay was about 500–800 mm (1.6–2.6 feet) long and attached to a combined flat wooden turnblock and multi V jamb cleat called an angel (maiden, virgin).

Early long boats used some form of steering oar but by the tenth century the side rudder (called a steerboard, the source for the etymology for the word starboard itself) was well established.

[21] At the height of Viking expansion into Dublin and Jorvik 875–954 AD the longship reached a peak of development such as the Gokstad ship 890.

Archaeological discoveries from this period at Coppergate, in York, show the shipwright had a large range of sophisticated woodwork tools.

As well as the heavy adze, broad axe, wooden mallets and wedges, the craftsman had steel tools such as anvils, files, snips, awls, augers, gouges, draw knife, knives, including folding knives, chisels and small 300 mm (12 inches) long bow saws with antler handles.

[22] The Vikings were experts in judging speed and wind direction, and in knowing the current and when to expect high and low tides.

[23] Hypothesis The Danish archaeologist Thorkild Ramskou suggested in 1967 that the "sun-stones" referred to in some sagas might have been natural crystals capable of polarizing skylight.

[27] To derive a course to steer relative to the sun direction, he uses a sun-stone (solarsteinn) made of Iceland spar (optical calcite or silfurberg), and a "horizon-board."

Karlsen also discusses why on North Atlantic trips the Vikings might have preferred to navigate by the sun rather than by stars, as at high latitudes in summer the days are long and the nights short.

Almgren, an earlier Viking, told of another method: "All the measurements of angles were made with what was called a 'half wheel' (a kind of half sun-diameter which corresponds to about sixteen minutes of arc).

At sea, the sail enabled longships to travel faster than by oar and to cover long distances overseas with far less manual effort.

The ship was steered by a vertical flat blade with a short round handle, at right angles, mounted over the starboard side of the aft gunwale.

The true Viking warships, or langskips, were long and narrow, frequently with a length-breadth ratio of 7:1; they were very fast under sail or propelled by warriors who served as oarsmen.

Some are just inspired by the longship design in general, while others are intricate works of experimental archaeology, trying to replicate the originals as accurately as possible.