Longtermism

It is an important concept in effective altruism and a primary motivation for efforts that aim to reduce existential risks to humanity.

"[8]: 52–53 In addition, Ord notes that "longtermism is animated by a moral re-orientation toward the vast future that existential risks threaten to foreclose.

Examples of these risks include nuclear war, natural and engineered pandemics, climate change and civilizational collapse, stable global totalitarianism, and emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and nanotechnology.

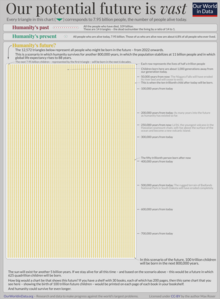

[18][19] Consequently, advocates of longtermism argue that humanity is at a crucial moment in its history where the choices made this century may shape its entire future.

Economist Tyler Cowen argues that increasing the rate of economic growth is a top moral priority because it will make future generations wealthier.

[5] He uses the abolition of slavery as an example, which historians like Christopher Leslie Brown consider to be a historical contingency rather than an inevitable event.

[27] At the same time, progress made in the physical and social sciences has given humanity the ability to more accurately predict (at least some) of the long-term effects of the actions taken in the present.

He introduces a three-part framework for thinking about effects on the future, which states that the long-term value of an outcome we may bring about depends on its significance, persistence, and contingency.

[6]: 32 Moreover, MacAskill acknowledges the pervasive uncertainty, both moral and empirical, that surrounds longtermism and offers four lessons to help guide attempts to improve the long-term future: taking robustly good actions, building up options, learning more, and avoiding causing harm.

Many advocates of longtermism accept the total view of population ethics, on which bringing more happy people into existence is good, all other things being equal.

[23] Effective altruism promotes the idea of moral impartiality, suggesting that people’s worth does not diminish simply because they live in a different location.

[33][34] Longtermists generally reject the notion of a pure time preference, which values future benefits less simply because they occur later.

[8]: 240–245 Toby Ord argues that a nonzero pure time preference applied to normative ethics is arbitrary and illegitimate.

Economist Frank Ramsey, who devised the discounting model, also believed that while pure time preference might describe how people behave (favoring immediate benefits), it does not offer normative guidance on what they should value ethically.

[36] One objection to longtermism is that it relies on predictions of the effects of our actions over very long time horizons, which is difficult at best and impossible at worst.

[37] In response to this challenge, researchers interested in longtermism have sought to identify "value lock in" events—events, such as human extinction, which we may influence in the near-term but that will have very long-lasting, predictable future effects.

For example, some critics have argued that considering humanity's future in terms of the next 10,000 or 10 million years might lead to downplaying the nearer-term effects of climate change.

[38] They also worry that the most radical forms of strong longtermism could in theory justify atrocities in the name of attaining "astronomical" amounts of future value.

[3] Anthropologist Vincent Ialenti has argued that avoiding this will require societies to adopt a "more textured, multifaceted, multidimensional longtermism that defies insular information silos and disciplinary echo chambers".

For example, funding research and innovation in antivirals, vaccines, and personal protective equipment, as well as lobbying governments to prepare for pandemics, may help prevent smaller scale health threats for people today.

[3] An illustration of this problem is Pascal’s mugging, which involves the exploitation of an expected value maximizer via their willingness to accept such low probability bets of large payoffs.