William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley

William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley (13 September 1520 – 4 August 1598) was an English statesman, the chief adviser of Queen Elizabeth I for most of her reign, twice Secretary of State (1550–1553 and 1558–1572) and Lord High Treasurer from 1572.

He also acquired the affections of Cheke's sister, Mary, and was in 1541 removed by his father to Gray's Inn, without having taken a degree, as was common at the time for those not intending to enter the Church.

[4] Cecil, according to his autobiographical notes, sat in Parliament in 1543; but his name does not occur in the imperfect parliamentary returns until 1547, when he was elected for the family borough of Stamford.

[8] But service under Warwick (by now the Duke of Northumberland) carried some risk, and decades later in his diary, Cecil recorded his release in the phrase "ex misero aulico factus liber et mei juris" ("I was freed from this miserable court").

[4] To protect the Protestant government from the accession of a Catholic queen, Northumberland forced King Edward's lawyers to create an instrument setting aside the Third Succession Act on 15 June 1553.

(The document, which Edward titled "My Devise for the Succession", barred both Elizabeth and Mary, the remaining children of Henry VIII, from the throne, in favour of Lady Jane Grey.)

"[13] In January of that year, he wrote to Sir Thomas Smith: "The Parliament is begun and I trust will be short, for matters of moment to pass are not many, reviving of some old laws for penalties of some felonies and the grant of a subsidy.

"[14] It was rumoured in December 1554 that Cecil would succeed Sir William Petre as Secretary of State, an office which, with his chancellorship of the Garter, he had lost on Mary's accession to the throne.

The story, even as told by his biographer,[15] does not represent Cecil's conduct as having been very courageous; and it is more revealing that he found no seat in the parliament of 1558, for which Mary had directed the return of "discreet and good Catholic members".

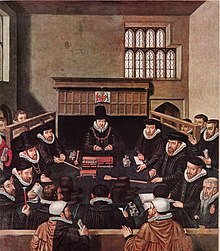

His tight control over the finances of the Crown, leadership of the Privy Council, and the creation of a capable intelligence service under the direction of Francis Walsingham made him the most important minister for the majority of Elizabeth's reign.

Dawson argues that Cecil's long-term goal was a united and Protestant British Isles, an objective to be achieved by completing the conquest of Ireland and by creating an Anglo-Scottish alliance.

He did obtain a firm Anglo-Scottish alliance reflecting the common religion and shared interests of the two countries, as well as an agreement that offered the prospect of a successful conquest of Ireland.

How far he was personally responsible for the Anglican Settlement, the Poor Laws, and the foreign policy of the reign, remains to a large extent a matter of conjecture.

Like the mass of the nation, he grew more Protestant as time wore on; he was happier to persecute Catholics than Puritans; and he had no love for ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

[21] His economic ideas were influenced by the Commonwealthmen of Edward VI's reign: he believed in the necessity of safeguarding the social hierarchy, the just price and the moral duties due to labour.

[24] William Cecil represented Lincolnshire in the Parliament of 1555 and 1559, and Northamptonshire in that of 1563, and he took an active part in the proceedings of the House of Commons until his elevation to the peerage; but there seems no good evidence for the story that he was proposed as Speaker in 1563.

[1] As Master of the Court of Wards, Cecil supervised the raising and education of wealthy, aristocratic boys whose fathers had died before they reached maturity.

His vacant post was offered to Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, who declined it and proposed Burghley, stating that the latter was the more suitable candidate because of his greater "learning and knowledge".

A new Theobalds House in Cheshunt was built between 1564 and 1585 by the order of Cecil, intending to build a mansion partly to demonstrate his increasingly dominant status at the Royal Court, and to provide a palace fine enough to accommodate the Queen on her visits.

Having survived all his children except Robert and Thomas, Burghley died at his London residence, Cecil House on 4 August 1598, and was buried in St Martin's Church, Stamford.

One of the latter branch, Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (1830–1903), served three times as Prime Minister, under Queen Victoria and her son, King Edward VII.

They describe the task of receiving and crafting a wide and large array of papers on behalf of Queen Elizabeth I and her Privy Council; finance, administration, foreign policy, and religion figure prominently, as does the shift from continental war to Ireland.

These letters reveal the intimate relationship between the father and son; Burghley's care for his family, his thoughts of death, and a unique record of illness and old age are framed by his political and spiritual anxieties for the future of the Queen and her realms.

In the end, White fell into a Dublin controversy over the confessions of an intriguing priest, which threatened the authority of the Queen's deputised government in Ireland; out of caution Cecil withdrew his longstanding protection and the judge was imprisoned in London and died soon after.

Elizabeth was jealous of her Scottish rival and, although he was at pains to stress that Mary in no way surpassed her in charm and beauty, White could well have forfeited his recently acquired favour had this relation been communicated to his queen; Cecil seems to have kept it from his royal mistress.

[40] In February 1581, White demonstrated his independence in council, refusing to sign a letter to the queen regarding Nicholas Malby's actions in the Munster rebellion since he was away in England during the deliberations of the meeting.

He continued to demonstrate his valuable insights to Burghley in regular correspondence throughout the period, including letters of December 1581 on the miseries of war, the need for temperate government, and his fear that the wild Irish were glad to see the weakness of English blood in Ireland.

In a missive of 13 September 1582 White complained of the unfriendly dealings of Lucas Dillon, his erstwhile companion and fellow Irish-born councillor, stating they had been for a long time of 'contrary minds'.

Cecil is portrayed by Ben Willbond in the BAFTA Award-winning children's comedy television series Horrible Histories; in the spin-off film, Bill (2015), he was played by Mathew Baynton.

He also appears in the alternative history Ruled Britannia, by Harry Turtledove, in which he and his son Sir Robert Cecil are conspirators and patrons of William Shakespeare in an attempt to restore Elizabeth to power after a Spanish invasion and conquest of England.