White swamphen

It was first encountered when the crews of British ships visited the island between 1788 and 1790, and all contemporary accounts and illustrations were produced during this time.

Although historical confusion has existed about the provenance of the specimens and the classification and anatomy of the bird, it is now thought to have been a distinct species endemic to Lord Howe Island and most similar to the Australasian swamphen.

When HMS Supply passed the island, the ship's commander named it after First Lord of the Admiralty Richard Howe.

Crews of the visiting ships captured native birds (including white swamphens), and all contemporary descriptions and depictions of the species were made between 1788 and 1790.

The accounts indicate that the population varied, and individual bird plumage was white, blue, or mixed blue-and-white.

Although he apparently never visited Lord Howe Island, White may have questioned sailors and based some of his description on earlier accounts.

The naturalist John Latham listed the bird as Gallinula alba in a later 1790 work, and wrote that it may have been a variety of purple swamphen (or "gallinule").

Although White said that the first specimen was obtained from Lord Howe Island, the provenance of the second has been unclear; it was originally said to have come from New Zealand, resulting in taxonomic confusion.

[2][9] A note by the naturalist Edgar Leopold Layard on a contemporary illustration of the bird by Captain John Hunter inaccurately stated that it only lived on Ball's Pyramid, an islet off Lord Howe Island.

The belief that the bird was simply an albino was held by several later writers, and many failed to notice that White cited Lord Howe Island as the origin of the Vienna specimen.

[13][14] In 1873, the naturalist Osbert Salvin agreed that the Lord Howe Island bird was similar to the takahē, although he had apparently never seen the Vienna specimen, basing his conclusion on a drawing provided by von Pelzeln.

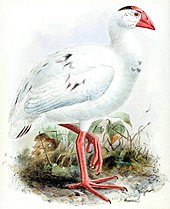

Salvin included a takahē-like illustration of the Vienna specimen by the artist John Gerrard Keulemans, based on von Pelzeln's drawing, in his article.

Rothschild published an illustration of N. alba by Keulemans where it is similar to a takahē, inaccurately showing it with dark primary feathers, although the Vienna specimen on which it was based is all white.

[19] In 1928, the ornithologist Gregory Mathews discussed a 1790 painting by Raper which he thought differed enough from P. albus in proportions and colouration that he named a new species based on it: P. raperi.

Mayr suggested that the blue swamphens remaining on Lord Howe Island were not stragglers, but had survived because they were less conspicuous than the white ones.

He suggested that the similarities between the wing feathers of the white swamphen and the takahē were due to parallel evolution in two isolated populations of reluctant fliers.

This indicates a complex history, since their lineages are not recorded on the islands between them; according to the biologists, such results (based on ancient DNA sources) should be treated with caution.

[2] In 2021, Hume and colleagues reported the results of their palaeontological reconnaissance of Lord Howe Island, which included the discovery of subfossil white swamphen bones.

A complete pelvis and representatives of most limb bones were found in the dunes of Blinky Beach (situated at the end of an airport runway), and the authors stated these would provide new insight into the morphology and behaviour of the species.

It differed from other swamphens in having blackish-blue lores, forehead, crown, nape, and hind neck; purple-blue mantle, back, and wings; a darker rump and upper-tail covert feathers; and dark greyish-blue underparts.

[25] Blackburn's 1788 account is the only one that mentions the diet of this bird: ... On the shore we caught several sorts of birds ... and a white fowl – something like a Guinea hen, with a very strong thick & sharp pointed bill of a red colour – stout legs and claws – I believe they are carnivorous they hold their food between the thumb or hind claw & the bottom of the foot & lift it to the mouth without stopping so much as a parrot.

Van Grouw and Hume found that both specimens showed evidence of an increased terrestrial lifestyle (including decreased wing length, more robust feet and short toes), and were in the process of becoming flightless.

Progressive greying is a common cause of white feathers in many types of birds (including rails), although such specimens have sometimes been inaccurately referred to as albinos.

The condition does not affect carotenoid pigments (red and yellow), and the bill and legs of the white swamphens retained their colouration.

The large number of white individuals on Lord Howe Island may be due to its small founding population, which would have facilitated the spread of inheritable progressive greying.

[2][8][29] Although the white swamphen was considered common during the late 18th century, it appears to have disappeared quickly; the period from the island's discovery to the last mention of living birds is only two years (1788–90).

[2][10][25] Several contemporary accounts stress the ease with which the island's birds were hunted, and the large number which could be taken to provision ships.

These not being birds of flight, nor in the least wild, the sailors availing themselves of their gentleness and inability to take wing from their pursuits, easily struck them down with sticks.

[2][3][26] The physician John Foulis conducted a mid-1840s ornithological survey on the island but did not mention the bird, so it was almost certainly extinct by that time.

[10] In 1909, the writer Arthur Francis Basset Hull expressed hope that the bird still survived in unexplored mountains.