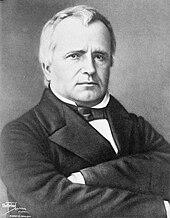

Louis-Michel Viger

One of Louis-Michel's uncles, Denis Viger, began as a carpenter but developed a business selling potash to English markets.

Denis-Benjamin Papineau, brother of Louis-Joseph, was also involved in provincial politics, and became joint premier of the new Province of Canada.

He quickly gained a reputation as a brilliant and popular young lawyer known for his diligence and competence, as well as his kindness.

His family connections gave him the entrée to many social settings in Montreal, and he acquired the nickname, Le beau Viger.

Canadiens of his generation were developing a new form of French-Canadian identity and nationalism, linked to self-government and liberty.

He was accused by two justices of the peace of disloyalty to the government and interfering in the electoral process, but no charges were laid.

In 1834, he voted in favour of the Ninety-Two Resolutions proposed by Papineau, highly critical of the colonial government and calling for substantive constitutional changes, including making the Legislative Council an elected body, instead of appointed by the Governor.

In the general elections later in 1834, the Parti canadien campaigned on the Ninety-Two Resolutions and won a strong majority in the assembly.

[1][7] Because of his intensive political involvement, Viger found he did not have time to continue with his legal practice after his election to the assembly.

Instead, in 1835 he entered into the banking business in partnership with wealthy Montreal businessman Jacob De Witt.

The initial capitalisation, provided by the twelve partners, was £75,000, a large portion coming from De Witt.

[1][2][8][9] Papineau was initially sceptical of Viger's plan, warning that the Banque would be "the tomb of your popularity and even your patriotism".

As time passed, Papineau became more approving, seeing the value of the Banque to counter the English dominance of business credit and financing in Lower Canada.

The Russell Resolutions would have increased the power of the Governor over the provincial finances, undercutting the existing authority of the elected Legislative Assembly.

He participated in public protest meetings organised by the Patriotes, and joined Papineau's call for a boycott of British goods.

At one of the most significant public rallies in October 1837, the Assembly of the Six Counties, Viger appeared on the platform with Papineau and spoke immediately after his cousin.

[1][2][12] As tensions grew, there were rumours that the Banque du Peuple was funnelling funds to the Patriotes to purchase arms and other supplies.

In particular, there were suspicions that Denis-Benjamin Viger, who was one of the leaders of the Patriote movement, may have had an undisclosed financial interest in the Banque.

He was defeated by John Yule, who supported the union and the British governor general, Lord Sydenham.

There was electoral violence, as was common at the time, and Viger was defeated by ten votes, after supporters of Yule seized control of the hustings.

When Metcalfe called the general elections in 1844, LaFontaine successfully challenged Denis-Benjamin Viger for control of the French-Canadian Group.

Papineau, returned from exile and also elected to the assembly, criticised Viger for taking an appointment in the union government that he had originally opposed.

It was an important measure for LaFontaine, to demonstrate that the new system of responsible government could satisfy the political needs of French-Canadians.

That night, Tory opponents of the bill began to riot in Montreal, eventually setting fire to the Parliament building.

Although he had supported the bill, Viger opposed the decision to move the Parliament from Montreal and resigned from the executive council in protest, continuing to sit as a backbencher in the assembly.

In 1845, he was appointed president of the Banque, a position he held for the rest of his life, with De Witt as vice-president.

[1][2] When he heard the news of Viger's death, Louis-Joseph Papineau wrote in a letter to Jean-Joseph Girouard, another veteran of the Patriote movement and the Rebellion: "My friend and kinsman of the heart and of boyhood, with whom I grew up like a brother, Louis Viger, only one year older than I, is gone, and I learn this just as I write to you.