Louis Armstrong

Coming to prominence in the 1920s as an inventive trumpet and cornet player, he was a foundational influence in jazz, shifting the focus of the music from collective improvisation to solo performance.

Armstrong rarely publicly discussed racial issues, to the dismay of fellow African Americans, but took a well-publicized stand for desegregation in the Little Rock crisis.

[20] Later, as an adult, Armstrong wore a Star of David given to him by his Jewish manager, Joe Glaser, until the end of his life, in part in memory of this family who had raised him.

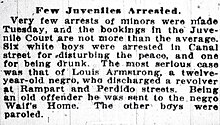

[13] His mother moved into a one-room house on Perdido Street with Armstrong, Lucy, and her common-law husband, Tom Lee, next door to her brother Ike and his two sons.

"[49] Among the Hot Five and Seven records were "Cornet Chop Suey", "Struttin' With Some Barbecue", "Hotter Than That", and "Potato Head Blues", all featuring highly creative solos by Armstrong.

[50] His recordings soon after with pianist Earl "Fatha" Hines, their famous 1928 "Weather Bird" duet and Armstrong's trumpet introduction to and solo in "West End Blues", remain some of the most influential improvisations in jazz history.

Armstrong was now free to develop his style as he wished, which included a heavy dose of effervescent jive, such as "Whip That Thing, Miss Lil" and "Mr. Johnny Dodds, Aw, Do That Clarinet, Boy!

In the last half of 1928, he started recording with a new group: Zutty Singleton (drums), Earl Hines (piano), Jimmy Strong (clarinet), Fred Robinson (trombone), and Mancy Carr (banjo).

[61] Armstrong returned to New York in 1929, where he played in the pit orchestra for the musical Hot Chocolates, an all-black revue written by Andy Razaf and pianist Fats Waller.

[62] Armstrong started to work at Connie's Inn in Harlem, chief rival to the Cotton Club, a venue for elaborately staged floor shows,[63] and a front for gangster Dutch Schultz.

His 1930s recordings took full advantage of the RCA ribbon microphone, introduced in 1931, which imparted warmth to vocals and became an intrinsic part of the "crooning" sound of artists like Bing Crosby.

In the first verse, Armstrong ignores the notated melody and sings as if playing a trumpet solo, pitching most of the first line on a single note and using strongly syncopated phrasing.

His resonant, velvety lower-register tone and bubbling cadences on sides such as "Lazy River" greatly influenced younger white singers such as Bing Crosby.

Armstrong hired Joe Glaser as his new manager, a tough mob-connected wheeler-dealer who began straightening out his legal mess, mob troubles, and debts.

Armstrong was featured as a guest artist with Lionel Hampton's band at the famed second Cavalcade of Jazz concert held at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, produced by Leon Hefflin Sr., on October 12, 1946.

This smaller group was called Louis Armstrong and His All-Stars and included at various times Earl "Fatha" Hines, Barney Bigard, Edmond Hall, Jack Teagarden, Trummy Young, Arvell Shaw, Billy Kyle, Marty Napoleon, Big Sid "Buddy" Catlett, Cozy Cole, Tyree Glenn, Barrett Deems, Mort Herbert, Joe Darensbourg, Eddie Shu, Joe Muranyi and percussionist Danny Barcelona.

He and his All-Stars were featured at the ninth Cavalcade of Jazz concert also at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles produced by Leon Hefflin Sr. held on June 7, 1953, along with Shorty Rogers, Roy Brown, Don Tosti and His Mexican Jazzmen, Earl Bostic, and Nat "King" Cole.

However, a growing generation gap became apparent between him and the young jazz musicians who emerged in the postwar era, such as Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, and Sonny Rollins.

The postwar generation regarded their music as abstract art and considered Armstrong's vaudevillian style, half-musician and half-stage entertainer, outmoded and Uncle Tomism.

[96] Armstrong generally remained politically neutral, which sometimes alienated him from black community members who expected him to use his prominence within white America to become more outspoken during the civil rights movement.

This was due to Armstrong's aggressive playing style and preference for narrow mouthpieces that would stay in place more easily but tended to dig into the soft flesh of his inner lip.

Many younger black musicians criticized Armstrong for playing in front of segregated audiences and for not taking a stronger stand in the American civil rights movement.

In 1957, journalism student Larry Lubenow scored a candid interview with Armstrong while the musician was performing in Grand Forks, North Dakota, shortly after the conflict over school desegregation in Little Rock, Arkansas.

[96] Armstrong's laxative of preference in his younger days was Pluto Water, but when he discovered the herbal remedy Swiss Kriss, he became an enthusiastic convert,[96] extolling its virtues to anyone who would listen and passing out packets to everyone he encountered, including members of the British Royal Family.

[117] During the krewe's 1949 Mardi Gras parade, Armstrong presided as King of the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club, for which he was featured on the cover of Time magazine.

In his records, Armstrong almost single-handedly created the role of the jazz soloist, taking what had been essentially a piece of collective folk music and turning it into an art form with tremendous possibilities for individual expression.

During his long career, Armstrong played and sang with some of the most important instrumentalists and vocalists of the time, including Bing Crosby, Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, Earl Hines, Jimmie Rodgers, Bessie Smith, and Ella Fitzgerald.

[96] The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz describes Crosby's debt to Armstrong in precise detail, although it does not acknowledge Armstrong by name: Crosby ... was important in introducing into the mainstream of popular singing an Afro-American concept of song as a lyrical extension of speech ... His techniques—easing the weight of the breath on the vocal cords, passing into a head voice at a low register, using forward production to aid distinct enunciation, singing on consonants (a practice of black singers), and making discreet use of appoggiaturas, mordents, and slurs to emphasize the text—were emulated by nearly all later popular singers.Armstrong recorded two albums with Ella Fitzgerald, Ella and Louis and Ella and Louis Again, for Verve Records.

His most familiar role was as the bandleader cum narrator in the 1956 musical High Society, starring Bing Crosby, Grace Kelly, Frank Sinatra, and Celeste Holm.

His honorary pallbearers included Bing Crosby, Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Pearl Bailey, Count Basie, Harry James, Frank Sinatra, Ed Sullivan, Earl Wilson, Benny Goodman, Alan King, Johnny Carson and David Frost.