Louis Blériot

He developed the first practical headlamp for cars and established a profitable business manufacturing them, using much of the money he made to finance his attempts to build a successful aircraft.

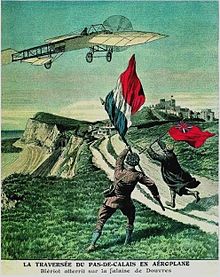

[9] In 1909 he became world-famous for making the first aeroplane flight across the English Channel, winning the prize of £1,000 offered by the Daily Mail newspaper.

In 1882, aged 10, Blériot was sent as a boarder to the Institut Notre Dame in Cambrai, where he frequently won class prizes, including one for engineering drawing.

He then embarked on a term of compulsory military service, and spent a year as a sub-lieutenant in the 24th Artillery Regiment, stationed in Tarbes in the Pyrenees.

[13] In October 1900 Blériot was lunching in his usual restaurant near his showroom when his eye was caught by a young woman dining with her parents.

[15] Blériot had become interested in aviation while at the Ecole Centrale, but his serious experimentation was probably sparked by seeing Clément Ader's Avion III at the 1900 Exposition Universelle.

The disappointment of the failure of his aircraft was compounded by the success of Alberto Santos Dumont later that day, when he managed to fly his 14-bis a distance of 220 m (720 ft), winning the Aéro Club de France prize for the first flight of over 100 metres.

On 6 August he managed to reach an altitude of 12 m (39 ft), but one of the blades of the propeller worked loose, resulting in a heavy landing which damaged the aircraft.

This, the Blériot VII, was a monoplane with tail surfaces arranged in what has become, apart from its use of differential elevators movement for lateral control, the modern conventional layout.

This was the most impressive achievement to date of any of the French pioneer aviators, causing Patrick Alexander to write to Major Baden Baden-Powell, president of the Royal Aeronautical Society, "I got back from Paris last night.

Blériot's determination is shown by the fact that during the flight at Douai made on 2 July part of the asbestos insulation worked loose from the exhaust pipe after 15 minutes in the air.

Three days later, on 19 June, he informed the Daily Mail of his intention to make an attempt to win the thousand-pound prize offered by the paper for a successful crossing of the English Channel in a heavier-than-air aircraft.

The others were Charles de Lambert, a Russian aristocrat with French ancestry, and one of Wilbur Wright's pupils, and Arthur Seymour, an Englishman who reputedly owned a Voisin biplane.

Also Wilbur had already amassed a fortune in prize money for altitude and duration flights and had secured sales contracts for the Wright Flyer with the French, Italians, British and Germans; his tour in Europe was essentially complete by the summer of 1909.

[31] Latham arrived in Calais in early July, and set up his base at Sangatte in the semi-derelict buildings which had been constructed for an 1881 attempt to dig a tunnel under the Channel.

The Marconi Company set up a special radio link for the occasion, with one station on Cap Blanc Nez near Sangatte and the other on the roof of the Lord Warden Hotel in Dover.

Leblanc went to bed at around midnight but was too keyed up to sleep well; at two o'clock, he was up, and judging that the weather was ideal woke Blériot who, unusually, was pessimistic and had to be persuaded to eat breakfast.

Altering course, he followed the line of the coast about a mile offshore until he spotted Charles Fontaine, the correspondent from Le Matin waving a large Tricolour as a signal.

The couple, surrounded by a cheering crowd and photographers, were then taken to the Lord Warden Hotel at the foot of the Admiralty Pier; Blériot had become a celebrity.

The Blériot Memorial, the outline of the aircraft laid out in granite setts in the turf (funded by oil manufacturer Alexander Duckham),[36] marks his landing spot above the cliffs near Dover Castle.

At the end of August, Blériot was one of the flyers at the Grande Semaine d'Aviation held at Reims, where he was narrowly beaten by Glenn Curtiss in the first Gordon Bennett Trophy.

Flying in gusty conditions to placate an impatient and restive crowd, he crashed on top of a house, breaking several ribs and suffering internal injuries: he was hospitalized for three weeks.

[20] Along with five other European aircraft builders, from 1910, Blériot was involved in a five-year legal struggle with the Wright Brothers over the latter's wing warping patents.

[43][44] In 1913, a consortium led by Blériot bought the Société pour les Appareils Deperdussin aircraft manufacturer and he became the president of the company in 1914.

ANEC survived in a difficult aviation climate until late 1926, producing Blériot-Whippet cars, the Blériot 500cc motorcycle,[47] as well as several light aircraft.

[48] In 1927, Blériot, long retired from flying, was present to welcome Charles Lindbergh when he landed at Le Bourget field completing his transatlantic flight.

The two men, separated in age by 30 years, had each made history by crossing significant bodies of water, and shared a photo opportunity in Paris.

The award was finally presented slightly more than three decades later by Alice Védères Blériot, widow of Louis Blériot, at Paris, France, 27 May 1961, to the crew of the United States Air Force Convair B-58A jet bomber, AF serial number 59-2451, Firefly, crewed by Aircraft Commander Major Elmer E. Murphy, Navigator Major Eugene Moses, and Defensive Systems Officer First Lieutenant David F. Dickerson who on 10 May 1961, sustained an average speed of 2,095 kmph (1,302.07 mph) over 30 minutes and 43 seconds, covering a ground track of 1,077.3 kilometers (669.4 miles).

The Blériot Trophy winning crew took over the aircraft for the return flight, but were all killed when the pilot lost control shortly after takeoff from the Paris Air Show during some attempted impromptu aerobatics.

[54] On 25 July 2009, the centenary of the original Channel crossing, Frenchman Edmond Salis took off from Blériot Beach in a replica of Bleriot's aircraft.