Louis Riel

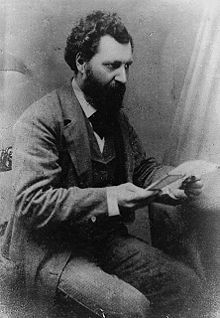

Louis Riel (/ˈluːi riˈɛl/; French: [lwi ʁjɛl]; 22 October 1844 – 16 November 1885) was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a political leader of the Métis people.

Riel was seen as a heroic victim by French Canadians; his execution had a lasting negative impact on Canada, polarizing the new nation along ethno-religious lines.

[1] Riel's historical reputation has long been polarized between portrayals as a dangerous religious fanatic and rebel opposed to the Canadian nation, and, by contrast, as a charismatic leader intent on defending his Métis people from the unfair encroachments by the federal government eager to give Orangemen-dominated Ontario settlers priority access to land.

[6][7] Sayer's eventual release due to agitations by Louis Sr.'s group effectively ended the monopoly, and the name Riel was therefore well known in the Red River area.

[12][16][17] Some of his friends said later that he worked odd jobs in Chicago, while staying with poet Louis-Honoré Fréchette,[18] and wrote poems himself in the manner of Lamartine, and that he was briefly employed as a clerk in Saint Paul, Minnesota, before returning to the Red River settlement on 26 July 1868.

[6][20] Bishop Taché and the HBC governor William Mactavish both warned the Macdonald government that the lack of consultation and consideration of Métis views would precipitate unrest.

[25] When summoned by the HBC-controlled Council of Assiniboia to explain his actions, Riel declared that any attempt by Canada to assume authority would be contested unless Ottawa had first negotiated terms with the Métis.

After large meetings on 19 and 20 January, Riel suggested the formation of a new convention split evenly between Francophone and Anglophone settlers to consider Smith's proposals.

When Archibald reviewed the troops in St. Boniface, he made the significant gesture of publicly shaking Riel's hand, signaling that a rapprochement had been effected.

However, following the early September defeat of George-Étienne Cartier in his home riding in Quebec, Riel stood aside so that Cartier—on record as being in favour of amnesty for Riel—might secure a seat in Provencher.

[46][6][47] During this period, Riel had been staying with the Oblate fathers in Plattsburgh, New York, who introduced him to parish priest Fabien Martin dit Barnabé in the nearby village of Keeseville.

But after Riel disrupted a religious service, Lee arranged to have him committed in an asylum in Longue-Pointe on 6 March 1876 under the assumed name "Louis R.

[48] While he suffered from sporadic irrational outbursts, he continued his religious writing, composing theological tracts with an admixture of Christian and Judaic ideas.

[6] In Pointe-au-Loup, Fort Berthold, Dakota Territory in 1881,[51][52] he married the young Métis Marguerite Monet dite Bellehumeur,[6] according to the custom of the country (à la façon du pays), on 28 April, the marriage being solemnized on 9 March 1882.

He brought a suit against a Democrat for rigging a vote, but was then himself accused of fraudulently inducing British subjects to take part in the election.

The Métis were likewise obliged to give up the hunt and take up agriculture—but this transition was accompanied by complex issues surrounding land claims similar to those that had previously arisen in Manitoba.

Virtually all parties therefore had grievances, and by 1884 Anglophone settlers, Anglo-Métis and Métis communities were holding meetings and petitioning a largely unresponsive government for redress.

[6] Upon his arrival Métis and Anglophone settlers alike formed an initially favourable impression of Riel following a series of speeches in which he advocated moderation and a reasoned approach.

During June 1884, the Plains Cree leaders Big Bear and Poundmaker were independently formulating their complaints, and subsequently held meetings with Riel.

In response to bribes by territorial lieutenant-governor and Indian commissioner Edgar Dewdney, local English-language newspapers adopted an editorial stance critical of Riel.

[6] Although Big Bear's forces managed to hold out until the Battle of Loon Lake on 3 June,[65] the Rebellion was a dismal failure for Indigenous communities.

The jury found him guilty but recommended mercy; nonetheless, Judge Hugh Richardson sentenced him to death on 1 August 1885, with the date of his execution initially set for 18 September 1885.

[6] Boulton writes in his memoirs that, as the date of his execution approached, Riel regretted his opposition to the defence of insanity and vainly attempted to provide evidence that he was not sane.

Louis Riel's pulse ceased four minutes after the trap-door fell and during that time the rope around his neck slowly strangled and choked him to death.

[77][78] By the mid-20th century academic historians had dropped the theme of savagery versus civilization, deemphasized the Métis, and focused on Riel, presenting his execution as a major cause of the bitter division in Canada along ethnocultural and geographical lines of religion and language.

W. L. Morton says of the execution that it "convulsed the course of national politics for the next decade": it was well received in Ontario, particularly among Orangemen, but francophone Quebec defended Riel as "the symbol, indeed as a hero of his race".

[82] However the clergy lost their influence during the Quiet Revolution, and activists in Quebec found in Riel the perfect hero, with the image now of a freedom fighter who stood up for his people against an oppressive government in the face of widespread racist bigotry.

[87] Edited by George Stanley, Raymond Huel, Gilles Martel, Thomas Flanagan and Glen Campbell, this work "ma[de] it possible to think comprehensively about Riel's life and his achievements", but was also criticized for some of its editorial decisions.

[88] In a 2010 speech, Beverley McLachlin, then Chief Justice of Canada, summed up Riel as being a rebel by the standards of the time but a patriot "viewed through our modern lens".

[99] In 1992, the House of Commons passed a resolution recognizing "the unique and historic role of Louis Riel as a founder of Manitoba and his contribution in the development of Confederation".