Edward Spears

Spears was born of British parents at 7 chaussée de la Muette in the fashionable district of Passy in Paris on 7 August 1886; France would remain the land of his childhood.

He claimed that the reason was his irritation at the mispronunciation of Spiers, yet it is possible that he wanted an English looking name – something more in keeping with his rank as a brigadier-general and head of the British Military Mission to the French War Office.

In today's age of radio communication, it is hard to believe that such vital information was often relayed personally by Spears, who travelled by car between the headquarters along roads clogged with refugees and retreating troops.

[13] Spears remained with Franchet d'Esperey after the Battle of the Marne until his posting at the end of September 1914 as liaison officer with the French Tenth Army, which was now under General Louis de Maud'huy near Arras.

[24] Spears became aware of Clemenceau's ruthlessness – 'probably the most difficult and dangerous man I have ever met' – and told London that he was 'out to wreck' the Supreme War Council at Versailles, France, being bent on its domination.

The complications continued with Spears fighting to maintain his position – telling Wilson that the antagonism of Foch stemmed from personal resentment, and calling upon support from his friend, Winston Churchill.

From May 1941, with funds provided by the British War Relief Society in New York, the medical unit served with Free French forces in the Middle East, North Africa, Italy and France.

'[37] Mary Borden died on 2 December 1968; her obituary in The Times pays tribute to her humanitarian work during both world wars and describes her as 'a writer of very real and obvious gifts'.

On a visit to Prague, he met Eduard Benes, the Prime Minister, and Jan Masaryk, son of the President; at the same time he came into contact with officials at the Czech Finance Ministry.

The book also contains a foreword by Winston Churchill, stating that Spears had not, in his view, been entirely fair to Lloyd George's wish to see Britain abstain from major offensives until the Americans were present in force.

This group, known disparagingly by the Conservative whips as 'The Glamour Boys', formed around Anthony Eden when he had resigned as Foreign Secretary in February 1938 in protest at the opening of negotiations with Italy by the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain.

He urged active support for the Poles and wanted Germany to be bombed; he was set to speak in the House criticizing the failure to aid Poland as a violation of the Anglo-Polish Agreement but was dissuaded by Secretary of State for Air Kingsley Wood – much to his later regret.

[55][56] As Chairman of the Anglo-French Committee of the House of Commons, he fostered links with his friends across the Channel, and in October 1939 led a delegation of MPs on a visit to the Chamber of Deputies of France when they were taken to the Maginot Line.

[61] During a visit to London on Sunday 26 May, the French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud had reported to Churchill the view of the new Commander-in-Chief General Maxime Weygand that the struggle had become hopeless.

Reynaud and Spears argued, the former calling for more British air support, the latter, exasperated, asking, "Why don't you import Finns and Spaniards to show the people how to resist an invader?

Italian entry into the war seemed imminent, with Churchill urging the bombing of the industrial north by British aircraft based in southern France while at the same time trying to gauge whether the French feared retaliation.

At the Chateau de Chissey high above the River Cher, he found Reynaud and his ministers struggling to govern France, but with insufficient telephone lines and in makeshift accommodation.

Spears found the atmosphere quite different from that at Briare, where Churchill had expressed good will, sympathy and sorrow; now it was like a business meeting, with the British keenly appraising the situation from its own point of view.

But the damage had been done and, on 23 June, the words would be quoted by Admiral François Darlan, who signalled all French warships saying that the British Prime Minister had declared that 'he understood' the necessity for France to bring the struggle to an end'.

The British took a hard line, pointing out that the solemn undertaking had been drawn up to meet the existing contingency; in any case, France [with its overseas possessions and fleet] was still in a position to carry on.

[80][81] Shortly before lunch a telegram arrived from London agreeing that France could seek armistice terms provided that the French fleet was sailed forthwith for British harbours pending negotiations.

[83] While the cabinet meeting was taking place, Spears and the Ambassador heard that Churchill, Clement Attlee, Sir Archibald Sinclair, the three Chiefs of Staff and others would arrive off Brittany in a warship the next day at noon for talks with the French.

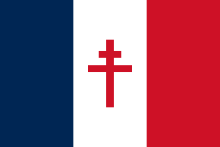

Winston Churchill wrote that Spears personally rescued de Gaulle from France just before the German conquest, literally pulling the Frenchman into his plane as it was taking off from Bordeaux for Britain.

Spears tried to encourage him and at the end of July in an unsuccessful attempt to rally support, flew to the internment camp at Aintree Racecourse near Liverpool, where French seamen who had been in British ports were taken as part of Operation Catapult.

"[98] On 23 September 1940, a landing by de Gaulle's troops was repulsed and, in the ensuing naval engagement, two British capital ships and two cruisers were damaged while the Vichy French lost two destroyers and a submarine.

[99] John Colville, Churchill's private secretary, wrote on 27 October 1940, "It is true that Spears' emphatic telegrams persuaded the Cabinet to revert to the Dakar scheme after it had, on the advice of the Chiefs of Staff, been abandoned".

De Gaulle and Spears held that it was essential to deny the Germans access to Vichy French Air Force bases in Syria from where they would threaten the Suez Canal.

However, his biggest bone of contention – one over which he frequently clashed with the Foreign Office and the Admiralty – was that a French ship, SS Providence, was allowed to sail unchallenged between Beirut and Marseille.

[106] De Gaulle and Spears held the view that the British at GHQ in Cairo were unwilling to accept that they had been duped over the level of collaboration between Germany and the Vichy-controlled states in the Levant.

[107] On 13 May 1941, the fears of de Gaulle and Spears were realised when German aircraft landed in Syria in support of the Iraqi rebel Rashid Ali, who was opposed to the pro-British Kingdom of Iraq.