Louisa Briggs

Louisa Briggs (née Strugnell; 14 November 1818 or 1836 – 6 or 8 September 1925) was an Aboriginal Australian rights activist, dormitory matron, midwife and nurse.

Her own account was that she was the daughter of a woman from the area around Port Phillip Bay named Mary and an English sealer, John Strugnell.

They took part in the Australian gold rushes of the 1850s and between prospecting, lived on the privately owned Eurambeen Station, where they did farm labour and worked as shepherds.

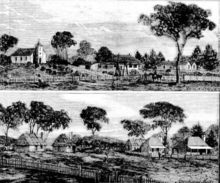

When the gold boom economy slowed, they were unable to find work and in 1871, moved to Coranderrk Aboriginal Station, a reserve which the government had created for the resettlement of the Boonwurrung and Woiwurrung people.

Her activism resulted in officials' decisions to keep her family separated between the two stations until 1882, but also eventually caused rations and wages at both reserves to be equalised.

The policy of excluding biracial people from the government stations was extended to Cummeragunja in 1895, and the family was forced to remove to a makeshift camp near Barmah.

She was honoured with a bronze plaque in the Pioneer Women's Memorial Garden in Melbourne and at Site 31 on the Bayside Coastal Indigenous Trail in Victoria.

Anthropological and historical attention to Aboriginal biographies did not emerge until the last-half of the twentieth century, when the anthropologist Diane Barwick began exploring their lives.

[1] Barwick acknowledged in 1985, that Australian interest in Aboriginal history was still lacking, despite pioneering work done by William Edward Hanley Stanner in the 1960s.

[11] The account is also disputed by Crawford Pasco's record of a meeting with Louisa at Coranderrk Station in which she told him that she and her mother had been abducted by Munro from Point Nepean and transported in his boat to Preservation Island, where she grew up.

[12] Diane Barwick reported that her death certificate showed that Louisa was born in Launceston, Tasmania, noting that information given by relatives in distress may be unreliable.

[23] Diane Barwick concluded that Louisa was probably the three-week-old child living with John Strugnell in 1837 on Preservation Island and whose death certificate showed she was born in Launceston.

[40] Robinson's rescue mission stopped on 9 January 1837,[41] on Preservation Island where he identified a Native woman from Port Phillip who was living with James Monro.

According to Fels, Diane Barwick concluded that Doog-by-er-um-bor-oke was Margery Munro and that Nan-der-gor-ok,[43] wife of the headman Derrimut,[38] was Elizabeth Maynard, but did not indicate how she connected the names.

[11] In examining a letter dated 1856 from William Wilson to the Lord Bishop of Tasmania, Ian D. Clark reported that Maria Munro and an aged woman named Gudague had been removed by Mr. Howie to Robbins Island.

[53] Munro died at the end of 1844 or beginning of 1845 and his obituary advised he had three children with an Aboriginal woman and his executor was to be Long Tom of Clarke Island.

[50] After examining the 1837 Robinson report and the 1863 Reibey report, Diane Barwick concluded that the daughter born in 1821 was likely Mary "Polly", based on Louisa's statement of her mother's name, Mary listed as a daughter on Margery's death certificate, and a statement from Morgan Mansell that his mother Eliza Bligh was the half-sister of Harry Strugnell.

[54] From genealogies published by L. W. G. Büchner in 1913,[55] by L. W. G. Malcolm in 1920,[56] and A. L. Meston in 1947,[57] Barwick gleaned the information that Polly was born in Western Port to a white man and that after her relationship to Strugnell ended she had two children, Eliza (c. 1846–1916) and Emma (c. 1849–1926) with Sam Bligh (or Blythe).

B. Plomley's Friendly Mission: The Tasmanian Journals and Papers of George Augustus Robinson, 1829–1834 (1966), that she was Ann Munro, who was a full-blooded Aboriginal woman and the first wife of John Briggs.

[12][Note 6] Louisa also told the geographers Lesley Hall and Dorothy Taylor in a 1924 interview that her birthday was 14 November, but she did not know the year, and repeated the information that she was taken with her mother as a child to Tasmania in a small boat.

Although some reports indicate George abducted Woretemoeteryenner, the fact that he had an amiable relationship for many years with her father, Mannalargenna the head man of the North East nation, points to an arranged partnership.

[76] John and his wives Ann and Louisa are listed in the Eurambeen Wages Book, as shepherds and shearers, as well as farm hands, between stints as prospectors.

That angered the station authorities which implemented the threat to expel John Briggs, but said as long as the children entered school, the family could remain.

[9] In an attempt to quash the unrest, in 1875 the board finally agreed to pay wages to the reserve residents and John Briggs was awarded a salary of six shillings per week.

[67] The Argus reported she was paid ten shillings per week for her services, which included serving as laundress, cook, child carer, nurse, and general administrator.

In response to an inquiry from the manager of Coranderrk as to whether the married children there should be reunited with her at Ebenezer, the missionary rejected the idea because keeping the family divided in different places would lessen their influence on other residents.

A move was implemented, but not codified by legislation until 1886, to require biracial people over the age of thirty-five to leave the reserves and be assimilated into the White culture.

[21] Hall and Taylor, who interviewed her at the Cummeragunja Reserve in 1924, chose her as a subject believing she was Tasmanian, but Louisa maintained her ancestry was Victorian.

[19][Note 8] Based upon ancestry, descendants from five abducted women, Louisa, Jane Foster, Elizabeth Maynard, Margery Munro, and Eliza Nowen were accepted by the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council as apical ancestors from whom Boonwurrung descent is established.

[96][97] The Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation challenged the heritage of Louisa, who is officially recognised as a foundational ancestor by the state of Victoria in a 2023 case filed in the Federal Court of Australia.