Louisiana Purchase Exposition gold dollar

Promoters of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, originally scheduled to open in 1903, sought a commemorative coin for fundraising purposes.

This drop, however, did not greatly affect Zerbe's career, as he went on to promote other commemorative coins and become president of the American Numismatic Association.

In 1682, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, claimed the entire area drained by the river for France, naming it Louisiana for Louis XIV.

Dreaming of a renewed French empire, he secured the return of the Louisiana territory from Spain via the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso the following year, and through other agreements.

[2] Desirous of honoring the centennial of the purchase, Congress passed authorizing legislation for an exposition; the bill was signed by President William McKinley on March 3, 1901.

[3] The bill in question authorized 250,000 gold one-dollar pieces to be paid over to the exposition organizers as part of the appropriation, upon their posting a bond that they would fulfill the requirements of the legislation.

[4] Anthony Swiatek and Walter Breen, in their encyclopedia of commemorative coins, suggested that the decision to have multiple designs was "through some unrecorded agreement".

[3] The legislation was ambiguous enough to permit such an interpretation, and numismatist Farran Zerbe urged the Mint to strike more than one type of coin, stating that sales would be increased if this was done.

In January 1903, an additional 175,178 pieces were coined; the excess of 258 over the authorized mintage was set aside for testing by the annual Assay Commission.

[3] Fifty thousand pieces were sent to the St. Louis sub-treasury on December 22, 1902, to await the organizing committee's compliance with other parts of the law, most likely relating to the required posting of a bond.

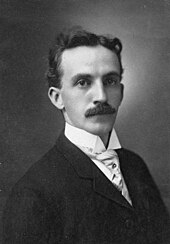

[11] Barber took the design for the Jefferson obverse from the former president's Indian Peace Medal, created by engraver John Reich, who used a bust by Jean-Antoine Houdon as his model.

[13] Others disagreed; Swiatek and Breen criticized the pieces, stating that Jefferson's "facial features, inaccurately rendered by Charles E. Barber, have acquired a resemblance to Napoleon Bonaparte, the other party in the Louisiana Purchase transaction.

"[3] Stating that McKinley was recognizable by his bow tie, they note of the reverse, "the olive branch—if that is the plant intended—may refer to this 828,000 square mile territory's acquisition by peaceful means".

[3] Numismatic historian Don Taxay criticized Reich's medal, stating that it "is hardly elegant, with Jefferson hunched unpleasantly in the circle as though placed there by a modern Procrustes".

[12] Taxay noted that Barber's rendition of McKinley for that medal had attracted the insult of "deadly" from the chief engraver's longtime enemy, sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

[12] Art historian Cornelius Vermeule criticized the Louisiana Purchase Exposition dollar and the Lewis and Clark Exposition dollar issued in 1904–1905: "the lack of spark in these coins, as in so many designs by Barber or [Assistant Engraver George T.] Morgan, stems from the fact that the faces, hair, and drapery are flat and the lettering is small, crowded, and even.

[14] Vermeule noted that contemporary accounts saw the 1903 issue as an innovation; a 1904 article in the American Journal of Numismatics stated that they "indicate a popular desire for a new departure from the somewhat monotonous types of Liberty which have characterized our money ...

Bowers, writing about a half century later, opined to the contrary; that in his experience and in grading service reports, the Jefferson coin was slightly more prevalent.

[17] Swiatek, in his 2012 book, prints statistics showing the number of pieces examined by the numismatic grading services, indicating more Jefferson dollars than McKinley.