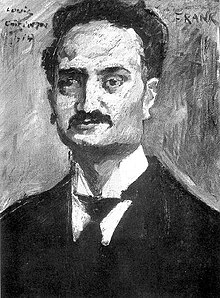

Ludwig Frank

At his instigation parliamentarians in Switzerland invited German and French counterparts to a conference in Bern in order to progress the project by devising international criminal justice mechanisms that could contribute to the peaceful settlement of disputes between governments.

[7] Ludwig Frank, the second of his parents' four recorded children, was born at Nonnenweier, a village positioned to the west of Lahr and short distance upriver of Kehl, on the strip of fertile flatlands that has paralleled the right-bank of the Rhine since the river was channelled.

Census data show that there were approximately 200 people identifying themselves as Jewish, and there is no indication that Frank encountered concrete race-based discrimination as he grew up, but he would have been conscious of the low-level background antisemitism that persisted across western Europe during the nineteenth century.

Sources are largely silent over how much his parents knew about the parallel curriculum that he pursued after school hours: it is a matter for speculation how they will have reacted when they discovered that their second son was growing into a "socialist intellectual".

In Karlsruhe the Education Ministry refused to provide the miscreant with his graduation certificate, relenting only after a large part of the press came out in support of the boy, and following a number of public protests.

[17] In 1900 Ludwig Frank embarked on a career as a lawyer in Mannheim, accepted as a junior partner by Dr. Julius Loeb, whose law firm he already knew as a result of having been employed there during his legal apprenticeship.

However, according to at least one source it came about only after Dr.Loeb, managing partner at the firm with which he had been working, proved reluctant to renew his contract, on account of concerns for his very active involvement with the Social Democrats - still perceived by many, even in traditionally liberal Baden, as a radical movement beyond the political mainstream.

[8] He also maintained cordial links to Mannheim's "haute-bourgeoisie" and intellectuals, and was a frequent presence at the salon events arranged by Bertha Hirsch, and was accordingly well networked with the artists, poets and culturally inclined politicians in the area.

Commentators characterise the collaboration in the Ständeversammlung between the SPD, the "free thinking radicals" and the Baden National Liberals as part of the emergence of a new more broadly based political bloc ("Großblock") of the centre-left.

As the second-largest party in the chamber, the SPD increased its political influence, although the fragmented character of the overall result meant that cross-party support remained essential for any pieces of substantive legislation.

He was unable to push through universal access to all the means of education, but was able to ensure that the obligation was placed on local authorities to provide school books for the children of impoverished parents.

It was only after the interior minister, Lord Heinrich von und zu Bodman of the National Liberals, had outlined a programme of positive collaboration with the SPD agenda on 13 July 1910 that Ludwig Frank felt able to recommend his parliamentary colleagues to relent.

[35] When the main election took place, on 21 October 1913, there was evidence of increased voter support for the conservatives and for the Catholic Centre Party, so that despite the underlying differences between them a number of hastily agreed run-off agreements for the second ballot came about.

August Bebel, the party leader, delivered the key-note speech in which he demanded that the conference should vote on a resolution expressly denouncing the attitude of the south German comrades from Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden.

Bebel made clear his judgement that by voting in support of regional government budgets the SPD parliamentarians in the south had shaken the credibility of the party's principles in the eyes of the working masses.

Frank, in his speech, also referenced Ferdinand Lassalle, the socialist pioneer who had alarmed Prussian censors some decades earlier with his repeated assertions that moral primacy in society belonged in the first instance to the working class rather than the bourgeoisie.

A corresponding reform policy [accessible already, at least in southern Germany, through coalition politics], should not be held back by a doctrinaire blanket ban on local SPD parliamentarians voting in support of regional budgets.

Paul Lensch published his attack in Die Neue Zeit, describing the Baden parliamentarians as "cretins" and "petty bourgeois" - a favourite term of abuse among those inclined to view Marxism more as a latter day religion than as a means of improving the lives of workers.

[38][a] Presumably it was in full expectation of the conversation being widely reported that immediately before the conference opened August Bebel confided to comrades that Ludwig Frank, who had once been his "darling" and his "Benjamin" was a terrible disappointment.

His wide-ranging speech on 15 February 1912 returned to the need for reform of the existing constituency boundaries which still disproportionately reduced the of the votes from working class electors in the densely populated urban districts.

Frank himself died four years before the three-class franchise was eliminated as part of a wide-ranging series of constitutional reforms that became politically unavoidable after the Emperor's abdication in 1918 opened the way for a republican government structure that would have been unthinkable in 1911.

Instead the Zabern Affair in 1913 suggested that, from the perspective of the emperor and his relentlessly ever more conservative government, the Reichsland of Elsaß-Lothringen enjoyed the status only of a privileged colony, and wider constitutional progress was off the agenda.

In the Reichstag there was protest and a surge in mistrust of the chancellor, following a realisation that the Prussian army units in Zabern/Saverne had been guilty of foolish over-reaction and gross lawlessness, and that the German government had felt unable to assert its authority over the military.

On 9 April 1913 Ludwig Frank addressed the chamber on behalf of the party, opposing the Army Bill and calling on members to get together with their colleagues in the French parliament ("Chambre des députés") in order to find a way out of the spiralling arms race.

On 12 June 1913 Ludwig Frank addressed a public meeting at Berlin-Wilmersdorf: he called for a general strike, which he saw as the only way to compel the necessary democratisation of the voting system in Germany's largest "state".

[54] Frank's advocacy of a mass strike to force an end to the Prussian three-class franchise was particularly remarkable because it came from a member of the party leadership in the Reichstag who was widely presumed to be representative of the SPD mainstream.

At the very same meeting at Wilmersdorf he came under attack from Rosa Luxemburg, who identified an incompatibility between Frank's willingness to co-operate in a government structure based on what she termed "bloc parties" in his home state of Baden (where, to be fair, the three-class franchise did not apply) and his advocacy of a mass strike to force a change in the voting system in Prussia.

[15] On 26 March 1913 he sent a letter to his old friend Emil Hauth, who by this time had moved on from his life as a school teacher and lodging house keeper in Lahr and become a journalist, working in Zürich on the Social Democratic daily newspaper "Volksblatt".

The assessment was one that Chancellor von Bethmann Hollweg, a cautious conservative instinctively loyal to the emperor who had appointed him, probably accepted, despite evidence of his personal reservations, at least with regard to anticipated future timelines.

By portraying the Russian empire as the true aggressor in the event of any future war, the government were able to win the hearts of many instinctive socialist supporters who had long regarded imperial Russia as a bastion of Tsarist reactionism, and thereby a constant threat to progressive political developments in the west.