Luxembourgish collaboration with Nazi Germany

These movements typically shared the following common characteristics: they were nationalist, anti-Semitic, hostile towards both capitalism and communism, and were made up of the lower middle class.

After this high point, though, its history was marked by quarrels and a lack of funds, and a year later it had faded into obscurity, while attempts to revive it during the German occupation failed.

[2] The Luxemburger Volksjugend (LVJ) / Stoßtrupp Lützelburg was more successful in gathering a determined core of young people, who followed Nazi ideology and saw Adolf Hitler as their leader.

On 19 May, there was a meeting of 28 individuals who had belonged to several of the above-mentioned fascist movements, and who called for Luxembourg to be incorporated into Germany as a Gau.

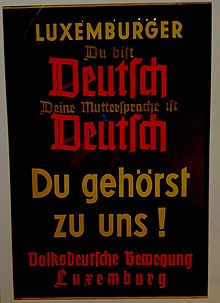

On 6 July 1940, when the VdB had not yet officially been founded, it released a public statement, declaring "Luxembourgers, hear the call of blood!

It tells you that you are German by race and by language [...]" Its aim was to persuade Luxembourgers to become an indistinguishable part of Nazi Germany.

Nevertheless, Nazism had such grave consequences in Luxembourg because there were people at every level of society who were ready to cooperate with the occupier, as illustrated by the 120 Ortsgruppenleiter (local branch leaders).

The Ortsgruppenleiter performed continual informer services throughout the war which allowed the German occupiers to keep the country under control for 4 years.

The authorities would ask an Ortsgruppenleiter for a political evaluation of an individual at many opportunities, for example when deciding whether to grant someone government benefits, membership in the VdB, access to education, leave for Wehrmacht members, or release from prison or concentration camps.

It became apparent that the VdB, being a mass organisation, was not suitable for forming a collaborationist elite, and so in September 1941 a Luxembourg section of the Nazi party was founded, which had grown to 4,000 members by the end of the war.

Other Nazi organisations such as the Hitler Youth, the Bund Deutscher Mädel, the Winterhilfswerk, the NS-Frauenschaft and the Deutsche Arbeitsfront were also introduced in Luxembourg.

These organisations subjected the country to a wave of propaganda, which aimed to bring the population "back into the [German] Empire" (Heim ins Reich).

Studies show that it was 30- to 40-year-olds who predominated; the Ortsgruppenleiter, however, were significantly younger than the local elites who would usually have filled political roles before the occupation.

[3] From the first months of the occupation, then, the Germans tried hard to bring Luxembourg's steel companies, Hadir, Ougreé-Marihaye and ARBED, under their control.

On 2 July 1940 Otto Steinbrinck, the Plenipotentiary for the Iron and Steel Industry in Luxembourg, Belgium and Northern France, called a meeting of the above companies' representatives.

However, when Nazi Germany moved to a strategy of total war, involving the mobilisation of all resources, the Armaments Minister Albert Speer ensured that from February 1942, Luxembourg's steel factories could work properly.

The production level of Luxembourg's heavy industry was neither held up by passive resistance on the part of the workers, nor obstruction by the management.

[3]: 28 It was also the Gauleiter who ensured that Meyer was named head of the Luxembourg section of the Wirtschaftsgruppe Eisen schaffende Industrie, and a member of the board of directors of the Reichsgruppe Eisen, a semi-public body that coordinated steel production from May 1942, and as president of the Gauwirtschaftskammer Moselland (Gau Moselland Chamber of Commerce).

[3]: 28 Meyer remained ARBED's managing director, and the company continued to produce steel, until the German occupying forces left the country in September 1944.

[4] The question as to ARBED's willingness to make concessions to the German authorities was already heavily discussed during the post-war trial of Aloyse Meyer, the managing director.

In early September 1944, about 10,000 people left Luxembourg with the German civil administration: it is generally assumed that this consisted of 3,500 collaborators and their families.

[2]: 134 Apart from their political activities, collaborators also had to account for their actions against Jews, denouncing forced conscripts in hiding, and spying on Luxembourg's population.

"[5] Since the 1980s, there has been a more nuanced state of affairs and the taboo has been at least partially lifted, as collaboration has been portrayed in works such as Roger Manderscheid's 1988 novel Schacko Klak, and the 1985 film Déi zwéi vum Bierg [lb].