Lymphatic system

[1] The primary (or central) lymphoid organs, including the thymus, bone marrow, fetal liver and yolk sac, are responsible for generating lymphocytes from immature progenitor cells in the absence of antigens.

[12] The thymus and the bone marrow constitute the primary lymphoid organs involved in the production and early clonal selection of lymphocyte tissues.

Avian species's primary lymphoid organs include the bone marrow, thymus, bursa of Fabricius, and yolk sac.

From the bone marrow, B cells immediately join the circulatory system and travel to secondary lymphoid organs in search of pathogens.

At puberty, by the early teens, the thymus begins to atrophy and regress, with adipose tissue mostly replacing the thymic stroma.

The secondary (or peripheral) lymphoid organs, which include lymph nodes and the spleen, maintain mature naive lymphocytes and initiate an adaptive immune response.

A study published in 2009 using mice found that the spleen contains, in its reserve, half of the body's monocytes within the red pulp.

[17][18][19] The spleen is a center of activity of the mononuclear phagocyte system and can be considered analogous to a large lymph node, as its absence causes a predisposition to certain infections.

[21] In the human until the fifth month of prenatal development, the spleen creates red blood cells; after birth, the bone marrow is solely responsible for hematopoiesis.

As a major lymphoid organ and a central player in the reticuloendothelial system, the spleen retains the ability to produce lymphocytes.

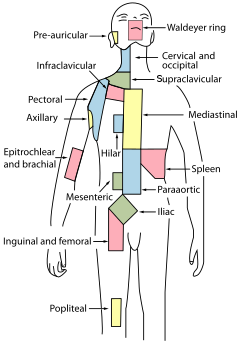

Lymph nodes are particularly numerous in the mediastinum in the chest, neck, pelvis, axilla, inguinal region, and in association with the blood vessels of the intestines.

Secondary lymphoid tissue provides the environment for the foreign or altered native molecules (antigens) to interact with the lymphocytes.

[28] TLOs typically contain far fewer lymphocytes, and assume an immune role only when challenged with antigens that result in inflammation.

Within these patients, lymphocytes in TLOs displayed an activated phenotype and in vitro experiments showed their capacity to perform effector functions.

[36] Lymphoid tissue associated with the lymphatic system is concerned with immune functions in defending the body against infections and the spread of tumours.

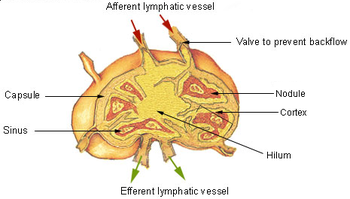

It consists of connective tissue formed of reticular fibers, with various types of leukocytes (white blood cells), mostly lymphocytes enmeshed in it, through which the lymph passes.

Its network of capillaries and collecting lymphatic vessels work to efficiently drain and transport extravasated fluid, along with proteins and antigens, back to the circulatory system.

From the jugular lymph sacs, lymphatic capillary plexuses spread to the thorax, upper limbs, neck, and head.

The lymphatic system has multiple interrelated functions:[43][44][45][46][47][48][49] Lymph vessels called lacteals are at the beginning of the gastrointestinal tract, predominantly in the small intestine.

(There are exceptions, for example medium-chain triglycerides are fatty acid esters of glycerol that passively diffuse from the GI tract to the portal system.)

[50] The lymphatic system (LS) comprises lymphoid organs and a network of vessels responsible for transporting interstitial fluid, antigens, lipids, cholesterol, immune cells, and other materials throughout the body.

Dysfunction or abnormal development of the LS has been linked to numerous diseases, making it critical for fluid balance, immune cell trafficking, and inflammation control.

Recent advancements, including single-cell technologies, clinical imaging, and biomarker discovery, have improved the ability to study and understand the LS, providing potential pathways for disease prevention and treatment.

Studies have shown that the lymphatic system also plays a role in modulating immune responses, with dysfunction linked to chronic inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, as well as cancer progression.

Rufus of Ephesus, a Roman physician, identified the axillary, inguinal and mesenteric lymph nodes as well as the thymus during the 1st to 2nd century AD.

[57] The findings of Ruphus and Herophilos were further propagated by the Greek physician Galen, who described the lacteals and mesenteric lymph nodes which he observed in his dissection of apes and pigs in the 2nd century AD.

[57] In the mid 16th century, Gabriele Falloppio (discoverer of the fallopian tubes), described what is now known as the lacteals as "coursing over the intestines full of yellow matter.

[57] The next breakthrough came when in 1622 a physician, Gaspare Aselli, identified lymphatic vessels of the intestines in dogs and termed them venae albae et lacteae, which are now known as simply the lacteals.

[62][63][64] Alexander Monro, of the University of Edinburgh Medical School, was the first to describe the function of the lymphatic system in detail.

[65] UVA School of Medicine researchers Jonathan Kipnis and Antoine Louveau discovered previously unknown vessels connecting the human brain directly to the lymphatic system.