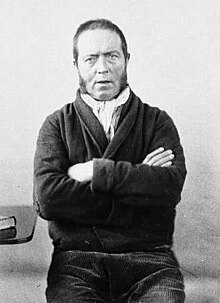

Daniel M'Naghten

Daniel M'Naghten (sometimes spelt McNaughtan or McNaughton; 1813 – 3 May 1865) was a Scottish woodturner who assassinated English civil servant Edward Drummond while suffering from paranoid delusions.

On the front page of the Scotch Reformers Gazette, supplementary edition for 4 March 1843, there appeared an artist's sketch of Daniel M'Naghten standing in the dock at Old Bailey, accompanied by an engraving of his signature.

While the Victorians were not always consistent in the way they spelt their names, even in official documents, several signatures of M'Naghten's father, uncovered while examining financial records at the Bank of Scotland, indicate that the "McNaughtan" spelling was the one used by the family.

When his father decided not to offer him a partnership, M'Naghten left the business and, after a three-year career as an actor, returned to Glasgow in 1835 to set up his own woodturning workshop.

On the afternoon of 20 January, the Prime Minister's private secretary, civil servant Edward Drummond, was walking towards Downing Street from Charing Cross when M'Naghten approached him from behind, drew a pistol and fired at point-blank range into his back.

His father successfully applied to the court to have the money released to finance his defence, and for the case to be adjourned for evidence relating to M'Naghten's state of mind to be gathered.

He went on to say that M'Naghten's delusions had led to a breakdown of moral sense and loss of self-control, which, according to medical experts, had left him in a state where he was no longer a "reasonable and responsible being".

Chief Justice Tindal, in his summing up, stressed that the medical evidence was all on one side and reminded the jury that if they found the prisoner not guilty on the ground of insanity, proper care would be taken of him.

[4] After his acquittal M'Naghten was transferred from Newgate Prison to the State Criminal Lunatic Asylum at Bethlem Hospital under the 1800 Act for the Safe Custody of Insane Persons charged with Offences.

Although no regular employment was provided for the men on the criminal wing of Bethlem, they were encouraged to keep themselves occupied with activities such as painting, drawing, knitting, board games, reading and musical instruments, and also did carpentry and decorating for the hospital.

[7] In 1864, M'Naghten was transferred to the newly opened Broadmoor Asylum, where his admission papers describe him as: "A native of Glasgow, an intelligent man" and record how, when asked if he thinks he must have been out of his mind when he shot Edward Drummond, he answers: "Such was the Verdict – the opinion of the Jury after hearing the Evidence.

Queen Victoria, who had been the target of assassination attempts, wrote to the prime minister expressing her concern at the verdict, and the House of Lords revived an ancient right to put questions to judges.

In England and Wales, the defence of insanity to which the rules apply was largely superseded, in cases of murder, by the Scottish concept of diminished responsibility following the passage of the Homicide Act 1957.

[6] M'Naghten's defence had successfully argued that he was not legally responsible for an act that arose from a delusion; the rules represented a step backwards to the traditional 'knowing right from wrong' test of criminal insanity.

[6] David Jones, lecturer in psychology at the Open University, sees the trial as a triumph for the emerging profession of psychiatry and its claims to professional expertise: "The dream of standing tall in the courts as experts in criminal insanity was very alluring to the gentlemen medics who sought a way out of the mire of dismal and stigmatized work in 'the madhouses'.

"[11] In 1843, a surgeon who was opposed to blood-letting published an anonymous pamphlet claiming that Drummond was killed not by M'Naghten's shot, but by the medical treatment he received afterwards.

[12] In his 1981 book Knowing Right From Wrong, Richard Moran, professor of sociology at Mount Holyoke College, argues that there are aspects of M'Naghten's case which have never been fully explained.