M1 Garand

[19] However, a 1952 issue of Armed Forces Talk, a periodical published by the U.S. Department of Defense, gives the pronunciation as /ɡəˈrænd/ gə-RAND, saying "popular usage has placed the accent on the second syllable, so that the rifle has become the 'guh-RAND'".

[23] In early 1928, both the infantry and cavalry boards ran trials with the .276 Pedersen T1 rifle, calling it "highly promising"[23] (despite its use of waxed ammunition,[24] shared by the Thompson).

The day after the successful conclusion of this test, Army Chief of Staff General Douglas MacArthur personally disapproved any caliber change, in part because there were extensive existing stocks of .30 M1 ball ammunition.

[25]: 113 Numerous problems were reported, forcing the rifle to be modified, yet again, before it could be recommended for service and cleared for procurement on 7 November 1935, then standardized 9 January 1936.

[27] Following the outbreak of World War II in Europe, Winchester was awarded an "educational" production contract for 65,000 rifles,[23] with deliveries beginning in 1943.

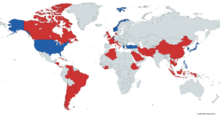

[36] Due to widespread United States military assistance as well as their durability, M1 Garands have also been found in use in recent conflicts such as with the insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In reality, this procedure was rarely performed in combat, as the danger of getting debris inside the action along with the cartridges increased the chances of malfunction.

Instead, it was much easier and quicker to simply manually eject the clip, and insert a fresh one,[46] which is how the rifle was originally designed to be operated.

[45][47][48] Later, special clips holding two (8+2=10 for target shooting) or five rounds (to meet hunting regulations) became available on the civilian market, as well as a single-loading device which stays in the rifle when the bolt locks back.

Due to the well-developed logistical system of the U.S. military at the time, this consumption of ammunition was generally not critical, though this could change in the case of units that came under intense fire or were flanked or surrounded by enemy forces.

[51] Some U.S. veterans recalling combat in Europe are convinced that German soldiers did respond to the ejection clang, and would throw an empty clip down to simulate the sound so the enemy would expose themselves.

Unless the gas tube could be quickly repainted, the resultant gleaming muzzle could make the M1 Garand and its user more visible to the enemy in combat.

[56] This enabled the shooter to fire his weapon while using winter gloves, which could get "stuck" on the trigger guard or not allow for proper movement of the finger.

This USMC 1952 sniper's rifle, or MC52, was an M1C with the commercial Stith Bear Cub scope manufactured by the Kollmorgen Optical Company under the military designation: telescopic sight - Model 4XD-USMC.

The MC52 was also too late to see extensive combat in Korea, but it remained in Marine Corps inventories until replaced by bolt-action rifles during the Vietnam War.

Flash hiders were of limited utility during low-light conditions around dawn and dusk, but were often removed as potentially detrimental to accuracy.

Other than the folding stock, the basic M1 rifle was essentially unchanged with the exception of the short barrel, a correspondingly shortened operating rod (and spring) and the lack of a front handguard.

While the M1E5 was more compact than the standard Garand rifle, the short barrel made it an unpleasant gun to fire—and the advantages were not judged to be sufficient to offset the disadvantages.

Only one example of the M1E5 was fabricated for testing, and the gun resides today in the Springfield Armory National Historic Site Museum.

Despite the concept being shelved at Springfield Armory, the idea of a shortened M1 rifle was still viewed as potentially valuable for airborne and jungle combat use.

The Ordnance Department was not responsive to these complaints coming in from the Pacific and maintained that the M1 rifle and M1 carbine each filled a specific niche.

[citation needed] Nonetheless, by late 1944, the Pacific Warfare Board (PWB) decided to move forward with the development of a shortened M1 rifle.

Since the previous M1E5 project was not widely disseminated, it is entirely possible that the PWB may not have been aware of Springfield Armory's development of a similar rifle, and conceived the idea independently.

While the members of the test committee liked the concept of the short M1 rifle, it was determined that the muzzle blast was excessive and was compared to a flash bulb going off in the darkened jungle.

The M1s shortened in the Philippines under the auspices of the PWB had been well-used prior to modification, and the conversion exhibited rather crude craftsmanship, including hand-cut splines on the barrel.

Demilitarized models are rendered permanently inoperable, unless proper techniques, tools, and replacement parts are used to restore the rifle to safe operation.

During the 1950s, Beretta produced Garands in Italy at the behest of NATO, by having the tooling used by Winchester during World War II shipped to them by the U.S. government.

The BM59 was essentially a rechambered 7.62×51mm NATO caliber M1 fitted with a removable 20-round magazine, folding bipod and a combined flash suppressor-rifle grenade launcher.

[72] United States citizens meeting certain qualifications may purchase U.S. military surplus M1 rifles through the Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP).

[74] A State Department spokesman said the administration's decision was based on concerns that the guns could fall into the wrong hands and be used for criminal activity.