Magnetohydrodynamic generator

MHD has been developed for use in combined cycle power plants to increase the efficiency of electric generation, especially when burning coal or natural gas.

The hot exhaust gas from an MHD generator can heat the boilers of a steam power plant, increasing overall efficiency.

In a conventional generator, rotating magnets move past a material filled with nearly-free electrons, typically copper wire (or vice versa depending on the design).

Ultimately the effect is the same, the working fluid is slowed down and cools as its kinetic energy is transferred to electrons, and is thereby converted to electrical power.

[3] MHD can only be used with power sources that produce large amounts of fast moving plasma, like the gas from burning coal.

This means it is not suitable for systems that work at lower temperatures or do not produce an ionized gas, like a solar power tower or nuclear reactor.

In the early days of development of nuclear power, one alternative design was the gaseous fission reactor, which did produce plasma, and this led to some interest in MHD for this role.

[citation needed] The Lorentz Force Law describes the effects of a charged particle moving in a constant magnetic field.

Heating a gas to its plasma state, or adding other easily ionizable substances like the salts of alkali metals, can help to accomplish this.

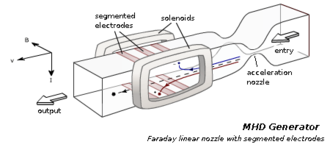

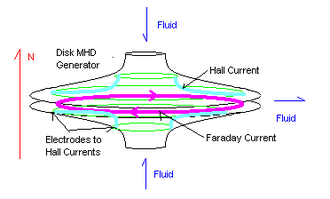

The main practical problem of a Faraday generator is that differential voltages and currents in the fluid may short through the electrodes on the sides of the duct.

However, this design has problems because the speed of the material flow requires the middle electrodes to be offset to "catch" the Faraday currents.

As very hot plasmas can only be used in pulsed MHD generators (for example using shock tubes) due to the fast thermal material erosion, it was envisaged to use nonthermal plasmas as working fluids in steady MHD generators, where only free electrons are heated a lot (10,000–20,000 kelvins) while the main gas (neutral atoms and ions) remains at a much lower temperature, typically 2500 kelvins.

The prospects of this technology, which initially predicted high efficiencies, crippled MHD programs all over the world as no solution to mitigate the instability was found at that time.

There are also risks of damage to the hot, brittle ceramics from differential thermal cracking: magnets are usually near absolute zero, while the channel is several thousand degrees.

[16] MHD generators have not been used for large-scale mass energy conversion because other techniques with comparable efficiency have a lower lifecycle investment cost.

The side walls and electrodes merely withstand the pressure within, while the anode and cathode conductors collect the electricity that is generated.

Coal-fired MHD plants with oxygen/air and high oxidant preheats would probably provide potassium-seeded plasmas of about 4200 °F, 10 atmospheres pressure, and begin expansion at Mach 1.2.

These plants would recover MHD exhaust heat for oxidant preheat, and for combined cycle steam generation.

With aggressive assumptions, one DOE-funded feasibility study of where the technology could go, 1000 MWe Advanced Coal-Fired MHD/Steam Binary Cycle Power Plant Conceptual Design, published in June 1989, showed that a large coal-fired MHD combined cycle plant could attain a HHV energy efficiency approaching 60 percent—well in excess of other coal-fueled technologies, so the potential for low operating costs exists.

There is simply an inadequate reliability track record to provide confidence in a commercial coal-fuelled MHD design.

Superconducting magnets are used in the larger MHD generators to eliminate one of the large parasitic losses: the power needed to energize the electromagnet.

The AVCO coal-fueled MHD generator at the CDIF was tested with water-cooled copper electrodes capped with platinum, tungsten, stainless steel, and electrically conducting ceramics.

In MHD coal plants, the patented commercial "Econoseed" process developed by the U.S. (see below) recycles potassium ionization seed from the fly ash captured by the stack-gas scrubber.

The first practical MHD power research was funded in 1938 in the U.S. by Westinghouse in its Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania laboratories, headed by Hungarian Bela Karlovitz.

Since membership in the ENEA was limited, the group persuaded the International Atomic Energy Agency to sponsor a third conference, in Salzburg, Austria, July 1966.

Engineers in former Yugoslavian Institute of Thermal and Nuclear Technology (ITEN), Energoinvest Co., Sarajevo, built and patented the first experimental Magneto-Hydrodynamic facility power generator in 1989.

[19][20] In the 1980s, the U.S. Department of Energy began a multiyear program, culminating in a 1992 50 MW demonstration coal combustor at the Component Development and Integration Facility (CDIF) in Butte, Montana.

The belief was that it would have higher efficiencies, and smaller equipment, especially in the clean, small, economical plant capacities near 100 megawatts (electrical) which are suited to Japanese conditions.

[21] The Italian program began in 1989 with a budget of about 20 million $US, and had three main development areas: A joint U.S.-China national programme ended in 1992 by retrofitting the coal-fired No.

This established centres of research in: The 1994 study proposed a 10 W (electrical, 108 MW thermal) generator with the MHD and bottoming cycle plants connected by steam piping, so either could operate independently.