Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya

Situated on Montjuïc hill at the end of Avinguda de la Reina Maria Cristina, near Pl Espanya, the museum is especially notable for its outstanding collection of romanesque church paintings, and for Catalan art and design from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including modernisme and noucentisme.

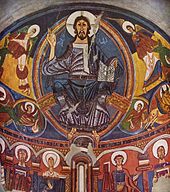

Hiring the Italian experts, from 1919 to 1923 they successfully intervened to detach many of the ecclesiastical frescos from the rural churches in the Pyrenees and transfer them to the Museum of Barcelona, then housed in the Parc de la Ciutadella.

Beside this superb piece stands another magnificent group of works, from Santa Maria de Taüll, the most important example of the interior of a Romanesque church painted throughout, with much of its decoration conserved today.

There are also sculptures in stone that form part of the Museu Nacional Romanesque art collection, particularly a number of works from Ripoll and a large group of elements from ensembles in the city of Barcelona, including the refined marble capitals from the former Hospital de Sant Nicolau.

[7] The Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya Gothic art collection began to take shape in the early decades of the 19th century, when a movement was first launched to revive and conserve the important body of Catalan heritage, which had been seriously damaged in the wave of convent burnings that took place at around the time of the disentailment of church goods in the year 1835.

As a whole, this section presents a broad, representative panoramic view of Gothic art produced in the three large peninsular territories that formed part of the Crown – Catalonia, Aragon itself, and Valencia – as well as a more anecdotal selection of works from Majorca.

It was also after a period in Valencia that Jaume Huguet, the great Catalan painter working in the second half of the 15th century, made his residence definitively in Barcelona, establishing his dominance and setting up a school there.

Besides this central strain in autochthonous painting, the panorama of Gothic art also features various other important episodes, such as the time spent by Antoine de Lonhy in Barcelona, or the later, longer residence in the Catalan capital of the Cordoban artist Bartolomé Bermejo, who had previously worked in Valencia and Aragon.

The itinerary begins with art from the Low Countries in the 16th century, in which religious fervour is mixed with detailed depiction of everyday life, as can be seen in the superb collection of panels and triptychs commissioned for private use.

The 17th century begins with the frescoes in the Herrera Chapel by Annibale Carracci and collaborators, who decorated the Church of San Giacomo degli Spagnuoli in Rome, and continues with works by other Italian artists such as the Neapolitans Massimo Stanzione and Andrea Vaccaro.

Finally, heralding the art forms that would develop in the 19th century, the daring works of Francesc Pla, known as El Vigatà, illustrate the painterly freedom taken when decorating the interiors of seigniorial mansions belonging to the new, wealthy classes who had made their fortunes in trade and industry.

It includes representative works of the Gothic and Renaissance periods, together with pieces that illustrate the perfection of the Italian Quattrocento, the sensuality of the great Venetian masters of the Cinquecento, the rising economic prosperity of the Low Countries in the 16th and 17th centuries and the magnificence of the Spanish Golden Age, without forgetting the richness of European Rococo.

The artists represented at the Museu Nacional, thanks to this distinguished collection, include many outstanding, universally known names: great Italian painters such as Sebastiano dal Piombo, Tiziano Vecellio (Titian) and Giandomenico Tiepolo; superb exponents of the Flemish School in the form of Peter Paul Rubens and Lucas Cranach; Jean-Honoré Fragonard and Maurice Quentin de la Tour and their French rococo works; and, finally, Francisco de Goya, whose revolutionary genius rounds off the artistic journey embraced by the Cambó Bequest.

[10] When the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection was installed in the Palacio de Villahermosa in Madrid, and the state formalised the purchase in 1993, a number of the works – 72 paintings and 8 sculptures, mainly on religious themes, though also including several landscapes and portraits – were dispatched on permanent loan to Barcelona.

There are many Italian works, including, most outstandingly, paintings by Fra Angelico, Pietro da Rimini, Taddeo Gaddi, Francesco del Cossa, Bernardino Butinone, Dosso Dossi, Titian, Ludovico Carracci, Tiepolo and Canaletto, among others.

Particularly fine examples from the Flemish school are a painting by Petrus Paulus Rubens and a landscape by Salomon Jacobz van Ruysdael, whilst the Spanish Golden Age is represented by Diego Velázquez's Portrait of Mariana of Austria.

In terms of Romanticism, particular mention should be made of Nazarene painters such as Claudi Lorenzale, who focussed on the portrait most notably, and Lluís Rigalt, a precursor of the Catalan landscape tradition, which was continued (now entering the Realist period) by Ramon Martí Alsina, who introduced Courbet's ideas in Catalonia, and Joaquim Vayreda, founder of the Olot School, among others.

The second generation of Modernista artists are present in depth and number, too, with works by the likes of Isidre Nonell, Marià Pidelaserra, Ricard Canals, Hermen Anglada–Camarasa, Nicolau Raurich and Joaquim Mir, among others.

The movement is represented by the classical compositions of Joaquín Torres García and Joaquim Sunyer, vaguely influenced by Cézanne, and the sculptural nudes of Josep Clarà and Enric Casanovas.

Finally, the new avant-garde that emerged during the post-war years is represented by Otho Lloyd and Joaquim Gomis, whose pioneering work found its continuation in the Neorealists Francesc Català-Roca, Joan Colom, Oriol Maspons and Xavier Miserachs, among others.

From the same period, moreover, are more than 30 drawings by the history painter Eduardo Rosales, acquired in 1912, and linked to two of his finest and most characteristic historic compositions: The Testament of Queen Isabella the Catholic and the Death of Lucrecia.

Dating back to the transition period between the ancient and medieval worlds is the collection of Visigoth coins, including some minted at workshops in Catalan territory, such as Barcino, Tarraco or Gerunda.

During the late 19th century, moreover, particularly after the 1888 Barcelona Exhibition, many Modernista sculptors turned to the art of medal-making, and the examples in the Cabinet fully reflect what was a splendid creative period for the genre, particularly in Catalonia.

The Palau Nacional is a huge building (over 50,000 square metres (540,000 sq ft)) which embodies the academic classical style that predominated in constructions for all the universal exhibitions of the period.

Entrance from the front is by a huge staircase leading up from Avinguda de la Reina Maria Cristina, flanked halfway by magnificent monumental illuminated fountains designed by Carles Buïgas.

The first projects to develop the slopes of Montjuïc, turning the mountain into the city's green lung and a leisure activity centre for the people of Barcelona, date back to the early 20th century.

The renowned Modernisme architect Josep Puig i Cadafalch was commissioned to direct the urban development and architectural aspects of this project, and Juan Claude Nicolas Forestier and Nicolau Maria Rubió i Tudurí landscaped the gardens.

[13] The Museu Nacional, as a museological institution of reference in the country, promotes a network that joins together the art museums in a common collaboration strategy, for placing value and spreading Catalan artistic heritage.

The department helps to guarantee the physical conservation of all the museum's holdings, including both works on exhibition and in storage, on deposit or on loan, whilst also seeking to delay as far as possible the ageing process that affects the materials that form the artworks.

The centre seeks to minimise deterioration to the collections by ensuring that the most appropriate environmental conditions and exhibition systems are provided, as well as exercising strict control over the movement of objects and the restoration treatments applied to individual works.