MPEG-1

[14] MPEG was formed to address the need for standard video and audio formats, and to build on H.261 to get better quality through the use of somewhat more complex encoding methods (e.g., supporting higher precision for motion vectors).

[17] The codecs that excelled in this testing were utilized as the basis for the standard and refined further, with additional features and other improvements being incorporated in the process.

[18] After 20 meetings of the full group in various cities around the world, and 4½ years of development and testing, the final standard (for parts 1–3) was approved in early November 1992 and published a few months later.

MPEG-1 Systems specifies the logical layout and methods used to store the encoded audio, video, and other data into a standard bitstream, and to maintain synchronization between the different contents.

This file format is specifically designed for storage on media, and transmission over communication channels, that are considered relatively reliable.

It reduces or completely discards information in certain frequencies and areas of the picture that the human eye has limited ability to fully perceive.

It also exploits temporal (over time) and spatial (across a picture) redundancy common in video to achieve better data compression than would be possible otherwise.

So much so that very high-speed and theoretically lossless (in reality, there are rounding errors) conversion can be made from one format to the other, provided a couple of restrictions (color space and quantization matrix) are followed in the creation of the bitstream.

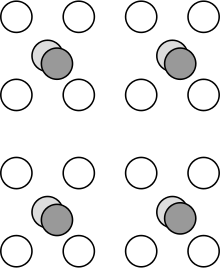

If a match is found, only the direction and distance (i.e. the vector of the motion) from the previous video area to the current macroblock need to be encoded into the inter-frame (P- or B- frame).

(See: qpel) Because neighboring macroblocks are likely to have very similar motion vectors, this redundant information can be compressed quite effectively by being stored DPCM-encoded.

An even more serious problem exists with macroblocks that contain significant, random, edge noise, where the picture transitions to (typically) black.

The FDCT process (by itself) is theoretically lossless, and can be reversed by applying an Inverse DCT (IDCT) to reproduce the original values (in the absence of any quantization and rounding errors).

Quantization is, essentially, the process of reducing the accuracy of a signal, by dividing it by some larger step size and rounding to an integer value (i.e. finding the nearest multiple, and discarding the remainder).

The frame-level quantizer is typically either dynamically selected by the encoder to maintain a certain user-specified bitrate, or (much less commonly) directly specified by the user.

A "quantization matrix" is a string of 64 numbers (ranging from 0 to 255) which tells the encoder how relatively important or unimportant each piece of visual information is.

An example quantized DCT block: Quantization eliminates a large amount of data, and is the main lossy processing step in MPEG-1 video encoding.

Since these lossless data compression steps don't add noise into, or otherwise change the contents (unlike quantization), it is sometimes referred to as noiseless coding.

Maximum compression can be achieved by a zig-zag scanning of the DCT block starting from the top left and using Run-length encoding techniques.

RLE is particularly effective after quantization, as a significant number of the AC coefficients are now zero (called sparse data), and can be represented with just a couple of bytes.

I- and P-frame sequences give moderate compression but add a certain degree of random access, FF/FR functionality.

The widespread usage of the term MUSICAM to refer to Layer II is entirely incorrect and discouraged for both technical and legal reasons.

The encoder then utilizes the psychoacoustic model to determine which sub-bands contain audio information that is less important, and so, where quantization will be inaudible, or at least much less noticeable.

[2][60][61][66] That (approximately) 1:6 compression ratio for CD audio is particularly impressive because it is quite close to the estimated upper limit of perceptual entropy, at just over 1:8.

[26] More recent testing has shown that MPEG Multichannel (based on MP2), despite being compromised by an inferior matrixed mode (for the sake of backwards compatibility)[2][61] rates just slightly lower than much more recent audio codecs, such as Dolby Digital (AC-3) and Advanced Audio Coding (AAC) (mostly within the margin of error—and substantially superior in some cases, such as audience applause).

MP3 works on 1152 samples like MP2, but needs to take multiple frames for analysis before frequency-domain (MDCT) processing and quantization can be effective.

[60] This extra granularity allows MP3 to have a much finer psychoacoustic model, and more carefully apply appropriate quantization to each band, providing much better low-bitrate performance.

[61] MP3 uses pre-echo detection routines, and VBR encoding, which allows it to temporarily increase the bitrate during difficult passages, in an attempt to reduce this effect.

[61] And yet in choosing a fairly small window size to make MP3's temporal response adequate enough to avoid the most serious artifacts, MP3 becomes much less efficient in frequency domain compression of stationary, tonal components.

MP3 has an aliasing cancellation stage specifically to mask this problem, but which instead produces frequency domain energy which must be encoded in the audio.

MP3 is also regarded as exhibiting artifacts that are less annoying than Layer II, when both are used at bitrates that are too low to possibly provide faithful reproduction.