Political machine

[3] Quoting Edward Flynn, a Bronx County Democratic leader who ran the borough from 1922 until his death in 1953,[4] Safire wrote "the so-called 'independent' voter is foolish to assume that a political machine is run solely on good will, or patronage.

Political machines started as grass roots organizations to gain the patronage needed to win the modern election.

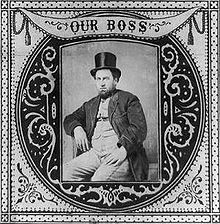

[7] Each city's machine lived under a hierarchical system with a "boss" who held the allegiance of local business leaders, elected officials and their appointees, and who knew the proverbial buttons to push to get things done.

However, Tammany Hall also served as an engine for graft and political corruption, perhaps most notoriously under William M. "Boss" Tweed in the mid-19th century.

[10] Lord Bryce describes these political bosses saying: An army led by a council seldom conquers: It must have a commander-in-chief, who settles disputes, decides in emergencies, inspires fear or attachment.

He generally avoids publicity, preferring the substance to the pomp of power, and is all the more dangerous because he sits, like a spider, hidden in the midst of his web.

[13] At the same time, the machines' staunchest opponents were members of the middle class, who were shocked at the malfeasance and did not need the financial help.

[15] In the 1930s, James A. Farley was the chief dispenser of the Democratic Party's patronage system through the Post Office and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) which eventually nationalized many of the job benefits machines provided.

Smaller communities such as Parma, Ohio, in the post–Cold War era under Prosecutor Bill Mason's "Good Old Boys" and especially communities in the Deep South, where small-town machine politics are relatively common, also feature what might be classified as political machines, although these organizations do not have the power and influence of the larger boss networks listed in this article.

[17][18][19][20] Political machines also thrive on Native American reservations, where tribal sovereignty is used as a shield against federal and state laws against the practice.

[21] In the 1960s and 1970s, Edward Costikyan, Ed Koch, Eleanor Roosevelt, and other reformers worked to do away with Tammany Hall of New York County.

[citation needed] Japan's Liberal Democratic Party is often cited as another political machine, maintaining power in suburban and rural areas through its control of farm bureaus and road construction agencies.

[24] Japanese political factional leaders are expected to distribute mochidai (literally snack-money) funds to help subordinates win elections.

Supporters collect benefits such as money payments distributed by politicians to voters in weddings, funerals, New year parties among other events, and ignore their patrons' wrongdoings in exchange.

In Mayors and Money, a comparison of municipal government in Chicago and New York, Ester R. Fuchs credited the Cook County Democratic Organization with giving Mayor Richard J. Daley the political power to deny labor union contracts that the city could not afford and to make the state government assume burdensome costs like welfare and courts.

At the same time, as Dennis R. Judd and Todd Swanstrom suggest in City Politics that this view accompanied the common belief that there were no viable alternatives.

He wrote that political machines created positive incentives for politicians to work together and compromise – as opposed to pursuing "naked self-interest" the whole time.