Madison Square and Madison Square Park

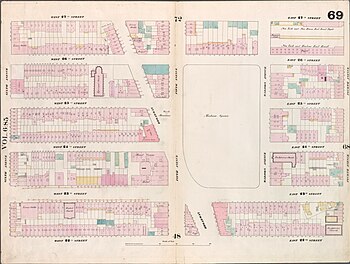

[3] In 1807, "The Parade", a tract of about 240 acres (97 ha) from 23rd to 34th Streets and Third to Seventh Avenues, was designated for use as an arsenal, a barracks, and a drilling area.

[4] There was a United States Army arsenal there from 1811 until 1825 when it became the New York House of Refuge for the Society for the Protection of Juvenile Delinquents, for children under sixteen committed by the courts for indefinite periods.

[4] In 1839, a farmhouse located at what is now Fifth Avenue and 23rd Street was turned into a roadhouse under the direction of William "Corporal" Thompson (1807–1872), who later renamed it "Madison Cottage", after the former president.

Initially, the houses around the park were narrow, crowded and dark brownstone rowhouses with small rooms easily subject to becoming cluttered.

[2] Despite this beginning, through the 1870s, the neighborhood became an aristocratic one of brownstone row houses and mansions where the elite of the city lived; Theodore Roosevelt, Edith Wharton and Winston Churchill's mother, Jennie Jerome, were all born here.

[7] Madison Square was also the site in November 1864 of a political rally, complete with torchlight parade and fireworks, in support of the presidential candidacy of Democrat General George B. McClellan, who was running against his old boss, Abraham Lincoln.

[11] It was the first hotel in the nation with elevators, which were steam powered and known as the "vertical railroad", which had the effect of making the upper floors more desirable as they no longer had to be reached by climbing stairs.

Notable visitors to the hotel included Mark Twain, Swedish singer Jenny Lind, railroad tycoon Jay Gould, financier "Big Jim" Fisk, the Prince of Wales and U.S. Presidents James Buchanan, Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, Chester A. Arthur, Grover Cleveland, Benjamin Harrison and William McKinley.

[2] The hotel, which was noted for its "Amen Corner" where Republican political boss Thomas Collier Platt held court in the 1890s,[2][13][14] was closed and demolished in 1908.

[2] With the center of the expanding city moving north by the turn of the century, and the neighborhood becoming commercialized, elite residents moved farther uptown, away from Madison Square, enabling more restaurants, theatres and clubs to open up in the neighborhood, creating an entertainment district, albeit an upscale one where society balls and banquets were held in restaurants such as Delmonico's.

[18] The city's Parks Department designated the area immediately around the monument as a parklet called General Worth Square.

One notable sculpture is the seated bronze portrait of Secretary of State William H. Seward, by Randolph Rogers (1876), which sits at the southwest entrance to the park.

[20] Other statues in the park depict Roscoe Conkling, who served in Congress in both the House and the Senate, and who collapsed at that spot in the park while walking home from his office during the Blizzard of 1888 and died five weeks later, after refusing to pay a cab $50 for the ride;[21][22] Chester Alan Arthur, the 21st President of the United States; and David Farragut, who is supposed to have said "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead" in the Battle of Mobile Bay during the Civil War.

The Farragut Memorial (1881), which was first erected at Fifth Avenue and 26th Street and moved to the Square's northern end in 1935,[23] was designed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (sculpture) and architect Stanford White (base).

[24] Along the south edge of the park is the Eternal Light Flagstaff, dedicated on Armistice Day 1923 and restored in 2002, which commemorates the return of American soldiers and sailors from World War I.

Eno later put a canvas screen on the wall, and projected images on it from a magic lantern on top of one of his smaller buildings on the lot, presenting both advertisements and interesting pictures in alternation.

Both the Times and the New York Tribune began using the screen for news bulletins, and on election nights crowds of tens of thousands of people would gather in Madison Square, waiting for the latest results.

[35] When the depot moved uptown in 1871 to Grand Central Depot, the building stood vacant until 1873, when it was leased to P. T. Barnum[34] who converted it into the open-air "Monster Classical and Geological Hippodrome" for circus performances, exhibits transferred from Barnum's American Museum, as well as cowboys and "Indians", tattooed men, bicycle races, dog shows, and horse shows.

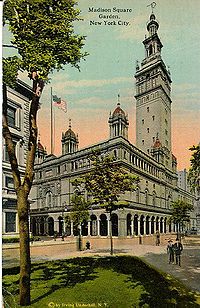

Vanderbilt eventually sold what Harper's Weekly called his "patched-up grimy, drafty combustible, old shell" to a syndicate that included J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, James Stillman and W. W.

The Garden hosted the annual French Ball, both the Barnum and the Ringling Brothers circuses, orchestral performances, light operas and romantic comedies, and the 1924 Democratic National Convention, which nominated John W. Davis after 103 ballots, but it was never a financial success.

Fifteen years passed, and in 1918 Mayor John F. Hylan had a Victory Arch built at about the same location to honor the city's war dead.

When a heat wave hit the city in July, people in Madison Park refused to pay the nickel that was now required to sit in the shade.

On July 11, Clausen annulled the city's 5-year contract with Spate (whose real name was Reginald Seymour), prompting a celebration with bands and fireworks in Madison Square Park attended by 10,000 people.

[39] Two months later, in September, the Seventy-first Regiment Band played "Nearer, My God, to Thee" in the park as recognition of the death by assassination of President William McKinley.

[42] Today the Madison Square Park Conservancy continues to present an annual tree-lighting ceremony sponsored by local businesses.

Phase one of the project, involving the north end of the park and Worth Square, was completed in 1988, and included the addition of a playground in the northeast corner.

Within the area, Madison Avenue continues to be primarily a business district, while Broadway just north of the square holds many small "wholesale" and import shops.

The Met Life Tower absorbed the site of the architecturally distinguished 1854 building of the former Madison Square Presbyterian Church, designed by architect Richard Upjohn on the southeast corner of 24th Street, while the Metropolitan Life North Building replaced the 1906 replacement church on the northeast corner of 24th Street and Madison, designed by Stanford White and demolished in 1919.

[61] Also of note is the statuary adorning the Appellate Division Courthouse of the New York State Supreme Court on Madison Avenue at 25th Street.

Madison Square can be reached on the New York City Subway via local service on the BMT Broadway Line (N, R, and W trains) at the 23rd Street station.