Madrid, Zaragoza and Alicante railway

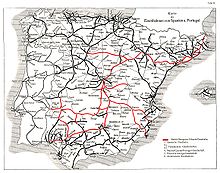

MZA rapidly expanded its railway concessions to encompass key routes in Extremadura, New Castile, Andalusia, and Levante, thereby gaining control of a significant market.

With control over the completed line in 1856, the Marquis of Salamanca connected with wealthy French businessmen already invested in the railway industry in Spain.

[3] The Rothschilds and others foresaw the creation of the Sociedad Española Mercantil e Industrial, which had Daniel Weisweiller and Ignacio Bauer as representatives, both of whom would play key roles in the future company.

On the opposite side were the Duke of Morny and several French administrators of the Chemin de Fer du Grand Central.

In 1845, the Spanish ambassador in London recommended and certain banks supported the proposition of a railway line connecting Madrid, Zaragoza, Pamplona, and Barcelona.

José de Salamanca, owner of Madrid-Aranjuez Railway, recognized a promising business opportunity and contacted the Rothschilds to propose merging their partially-operational Mediterranean line with a joint concession.

For unclear reasons, Bauer and Jose de Salamanca decided to employ the services of a front man - the wealthy local landowner, Marquis of Villamediana - who successfully obtained the concession against banker Guilhou.

[8] From the outset of the company, there were plans to expand the network to the southern regions in preparation for acquiring key routes to Andalusia and its ports, as well as through La Mancha.

In December 1858, shortly after its establishment, the company made its initial acquisition, the Compañía del Ferrocarril de Castillejo a Toledo, owned by the Marquis of Salamanca.

Initially, the Company planned to participate in the auction but later decided to do so indirectly through its advisors Salamanca and Baüer, who in turn negotiated an agreement with the Marquis of Villamediana.

There was already a precedent in 1856 when the Grand Central received a concession to start from Madrid-Almansa and enter the province of Jaen, then continue to Cordoba through the valley of Guadalquivir.

Sections III and IV would be retained by Jorge Loring y Oyarzábal and become a part of Compañía del Ferrocarril de Córdoba a Málaga.

Construction work continued in the ensuing years despite facing some economic and geographical challenges, until finally reaching Aragonese lands.

This period coincided with the economic downturn at the end of Isabella II's reign, as well as her widespread disapproval among many sectors of Spanish society.

Despite these challenges, Cipriano Segundo Montesino, the first Spaniard to hold this position, assumed management of the company in the following year.

The MZA had a network spanning 1428 km and was poised for expansion, not through new construction, but by acquiring and incorporating existing lines facing economic hardship.

This allowed Madrid to Zaragoza and Alicante Company to connect this railway with its own, which reached Cordoba and enabled access to the Andalusian region's capital.

[16] The merger policy was finalized with the rescue of the Compañía del Ferrocarril de Mérida a Sevilla in 1880, although it was granted with the concession since the line works had not begun yet.

[19] MZA also planned to construct another rail link with the North, which would begin at Ariza (on the Madrid-Zaragoza railway) and extend to Valladolid, passing through Aranda de Duero.

At the time, the TBF was building a direct line from Barcelona to Zaragoza, on a route much further south than the one operated by the Compañía del Norte via Lleida and Manresa.

[23] Prior to the partnership, it was agreed that MZA would construct the 254 km Valladolid-Ariza Railway line to establish a stronghold in Castilla la Vieja, a region traditionally controlled by Compañía del Norte.

This caught the attention of Madrid-Alicante, who considered buying shares in MTM to gain a percentage of the company and secure better prices for future orders.

This statute established state aid and subsidies for various railway companies to enhance their outdated and obsolete network and rolling stock.

MZA utilized this aid to enhance its network and complete various construction works, including the Barcelona terminus station which was finished in 1929.

Following the Crash of 1929 and the refusal of new Republican governments to recognize the validity of the Railway Statute of 1924, the company's accounts declined along with the overall economic crisis.

The war situation prompted the Republican government to nationalize all railways within its zone in order to guarantee control, although in practice they were collectivized by committees of workers and railwaymen.

Despite being the legal owners and having reconstructed the organization, the Francoist military authorities would direct and administer everything related to the railways because they were crucial for the war.

In many small yet significant details, the legacy of MZA continues to exist, as evidenced in places such as the train stations in Murcia and Cartagena.

Even at Atocha station in Madrid, one can spot the inscription "Madrid-Zaragoza-Alicante" on the upper part of the walls, a distant reminder of the company's period of glory.

At Atocha station in Madrid, the legend Madrid-Zaragoza-Alicante can still be seen on the upper part of the sides, a distant memory of its period of splendor under the company.