Magellan (spacecraft)

[2] The Magellan probe was the first interplanetary mission to be launched from the Space Shuttle, the first one to use the Inertial Upper Stage booster, and the first spacecraft to test aerobraking as a method for circularizing its orbit.

They first sought to construct a spacecraft named the Venus Orbiting Imaging Radar (VOIR), but it became clear that the mission would be beyond the budget constraints during the ensuing years.

[3] Hughes Aircraft Company's Space and Communications Group designed and built the spacecraft's synthetic aperture radar.

[1] The spacecraft's attitude control (orientation) was designed to be three-axis stabilized, including during the firing of the Star 48B solid rocket motor (SRM) used to place it into orbit around Venus.

Final conservative estimates of worst-case side forces resulted in the need for eight 445 N thrusters, two in each quadrant, located out on booms at the maximum radius that the Space Shuttle Orbiter Payload Bay would accommodate (4.4-m or 14.5-ft diameter).

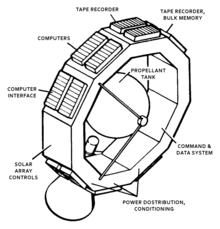

[10] The actual propulsion system design consisted of a total of 24 monopropellant hydrazine thrusters fed from a single 71cm (28 in) diameter titanium tank.

When communicating with the Deep Space Network, the spacecraft was able to simultaneously receive commands at 1.2 kilobits/second in the S-band and transmit data at 268.8 kilobits/second in the X-band.

Magellan addressed this problem by using a method known as synthetic aperture, where a large antenna is imitated by processing the information gathered by ground computers.

The Magellan high-gain parabolic antenna, oriented 28°–78° to the right or left of nadir, emitted thousands of microwave pulses per second that passed through the clouds and to the surface of Venus, illuminating a swath of land.

The Radar System then recorded the brightness of each pulse as it reflected back off the side surfaces of rocks, cliffs, volcanoes and other geologic features, as a form of backscatter.

To increase the imaging resolution, Magellan recorded a series of data bursts for a particular location during multiple instances called, "looks".

After transmitting the data back to Earth, Doppler modeling was used to take the overlapping "looks" and combine them into a continuous, high resolution image of the surface.

– In the Synthetic Aperture Radar mode, the instrument transmitted several thousand long-wave, 12.6-centimeter microwave pulses every second through the high-gain antenna, while measuring the doppler shift of each hitting the surface.

– In Altimetry mode, the instrument interleaved pulses with SAR, and operating similarly with the altimetric antenna, recording information regarding the elevation of the surface on Venus.

Magellan was planned to be launched with a liquid-fueled, Centaur G upper-stage booster, carried in the cargo bay of the Space Shuttle.

However, the entire Centaur G program was canceled after the Challenger disaster, and the Magellan probe had to be modified to be attached to the less-powerful Inertial Upper Stage.

[11][12] During each orbit, the space probe captured radar data while the spacecraft was closest to the surface, and then transmitted it back to Earth as it moved away from Venus.

This maneuver required extensive use of the reaction wheels to rotate the spacecraft as it imaged the surface for 37-minutes and as it pointed toward Earth for two hours.

Instead, beginning mid-September 1992, the Magellan maintained pointing of the high-gain antenna toward Earth where the Deep Space Network began recording a constant stream of telemetry.

This constant signal allowed the DSN to collect information on the gravitational field of Venus by monitoring the velocity of the spacecraft.

Testing a new approach to the method, a plan was devised to drop the orbit of Magellan into the outermost region of the Venusian atmosphere.

During the experiment, the spacecraft was oriented with the solar arrays broadly perpendicular to the orbital path, where they could act as paddles as they impacted molecules of the upper-Venusian atmosphere.

Magellan, however, finally allowed detailed imaging and analysis of craters, hills, ridges, and other geologic formations, to a degree comparable to the visible-light photographic mapping of other planets.

Due to the degradation of the power output from the solar arrays and onboard components, and having completed all objectives successfully, the mission was to end in mid-October.

The termination sequence began in late August 1994, with a series of orbital trim maneuvers which lowered the spacecraft into the outermost layers of the Venusian atmosphere to allow the Windmill experiment to begin on September 6, 1994.

The experiment lasted for two weeks and was followed by subsequent orbital trim maneuvers, further lowering the altitude of the spacecraft for the final termination phase.

[24] On October 11, 1994, moving at a velocity of 7 kilometers/second, the final orbital trim maneuver was performed, placing the spacecraft 139.7 kilometers above the surface, well within the atmosphere.

Although much of Magellan was expected to vaporize due to atmospheric stresses, some amount of wreckage is thought have hit the surface by 20:00:00 UTC.

This was not a problem since spacecraft power would have been too low to sustain operations in the next few weeks due to continuing solar cell loss.