Magnetic confinement fusion

After the declassification of fusion research by the United States, United Kingdom and Soviet Union in 1958, a breakthrough on toroidal devices was reported by the Kurchatov Institute in 1968, where its tokamak demonstrated a temperature of 1 kilo-electronvolts (around 11.6 million degree Kelvin) and some milliseconds of confinement time, and was confirmed by a visiting team from the Culham Laboratory using the Thomson scattering technique.

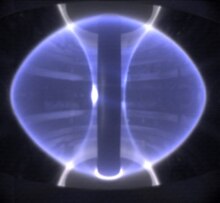

The ITER tokamak experiment under construction, which aims to demonstrate scientific breakeven, will be the world's largest MCF device.

[4] One of the challenges of MCF research is the development and extrapolation of plasma scenarios to power plant conditions, where good fusion performance and energy confinement must be maintained.

Potential solutions to other problems such as divertor power exhaust, mitigation of transients (disruptions, runaway electrons, edge-localized modes), handling of neutron flux, tritium breeding and the physics of burning plasmas are being actively studied.

Development of new technologies in plasma diagnostics, real-time control, plasma-facing materials, high-power microwave sources, vacuum engineering, cryogenics and superconducting magnets are essential in MCF research.

In 1954, Edward Teller gave a talk in which he outlined a theoretical problem that suggested the plasma would also quickly escape sideways through the confinement fields.

By placing a baseball coil at either end of a large solenoid, the entire assembly could hold a much larger volume of plasma, and thus produce more energy.

Notable among them was the kink instability, which caused the pinched ring to thrash about and hit the walls of the container long before it reached the required temperatures.

This led to the "stabilized pinch" concept, which added external magnets to "give the plasma a backbone" while it compressed.

Only a few months after its public announcement in January 1958, these claims had to be retracted when it was discovered the neutrons being seen were created by new instabilities in the plasma mass.

Further studies showed any such design would be beset with similar problems, and research using the z-pinch approach largely ended.

Essentially the stellarator consists of a torus that has been cut in half and then attached back together with straight "crossover" sections to form a figure-8.

Not long after the construction of the earliest figure-8 machines, it was noticed the same effect could be achieved in a completely circular arrangement by adding a second set of helically wound magnets on either side.

In addition to the fuel loss problems, it was also calculated that a power-producing machine based on this system would be enormous, the better part of a thousand feet (300 meters) long.

In 1968 Russian research on the toroidal tokamak was first presented in public, with results that far outstripped existing efforts from any competing design, magnetic or not.

One researcher has described the magnetic confinement problem in simple terms, likening it to squeezing a balloon – the air will always attempt to "pop out" somewhere else.

If this happens, a process known as "sputtering", high-mass particles from the container (often steel and other metals) are mixed into the fusion fuel, lowering its temperature.

In 1997, scientists at the Joint European Torus (JET) facilities in the UK produced 16 megawatts of fusion power.

[9] The progress made with SPARC has built off previously mentioned work on the ITER project and is aiming to utilize new technology in high-temperature superconductors (HTS) as a more practical material.

The program is installing additional tools to optimize tokamak operation and exploring edge plasma and materials interactions.

[18][19][20] The experiments will test the optimized concept of Wendelstein 7-X as a stellarator fusion device for potential use in a power plant.

The device's microwave heating system has also been improved to achieve higher energy throughput and plasma density.

The experiments were conducted in collaboration with Japan's National Institute for Fusion Science using a boron powder injection system developed by scientists and engineers of the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory.

TAE Technologies is focused on developing a fusion power plant by the mid-2030s that will produce clean electricity.

The grant recipients will tackle scientific and technological hurdles to create viable fusion pilot plant designs in the next 5–10 years.