Magnus Hirschfeld

[12] However, the officer mentioned at the end of his suicide note: "The thought that you [Hirschfeld] could contribute a future when the German fatherland will think of us in more just terms sweetens the hour of my death.

In 1897, Hirschfeld founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee with the publisher Max Spohr (1850–1905), the lawyer Eduard Oberg[22] (1858–1917), and the writer Franz Joseph von Bülow[23] (1861–1915).

[27] A figure frequently mentioned by Hirschfeld to illustrate the "hell experienced by homosexuals" was Oscar Wilde, who was a well-known author in Germany, and whose trials in 1895 had been extensively covered by the German press.

[28] Hirschfeld noted "the name Wilde" has, since his trial, sounded like "an indecent word, which causes homosexuals to blush with shame, women to avert their eyes, and normal men to be outraged".

[30] In 1906, Hirschfeld was asked as a doctor to examine a prisoner in Neumünster to see if he was suffering from "severe nervous disturbances caused by a combination of malaria, blackwater fever, and congenital sexual anomaly".

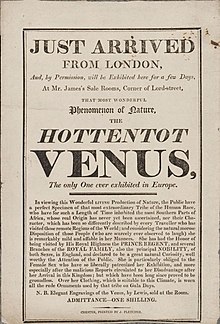

[33] At the same time, Hirschfeld became involved in a debate with a number of anthropologists about the supposed existence of the Hottentottenschürze ('Hottentot apron'), namely the belief that the Khoekoe (known to Westerners as Hottentots) women of southern Africa had abnormally enlarged labia, which made them inclined toward lesbianism.

[34] However, Bauer wrote that Hirschfeld's theories about the universality of homosexuality paid little attention to cultural contexts, and criticized him for his remarks that Hausa women in Nigeria were well known for their lesbian tendencies and would have been executed for their sapphic acts before British rule, as assuming that imperialism was always good for the colonized.

[42] Hirschfeld had been threatened by the Prussian government with having his medical license revoked if he testified as an expert witness again along the same lines that he had at the first trial, and possibly prosecuted for violating Paragraph 175.

[42] The trial was a libel suit against Harden by Moltke, but much of the testimony had concerned Eulenburg, whose status as the best friend of Wilhelm II meant that the scandal threatened to involve the Kaiser.

Hirschfeld was both quoted and caricatured in the press as a vociferous expert on sexual matters; during his 1931 tour of the United States, the Hearst newspaper chain dubbed him "the Einstein of Sex".

[55][56] Hirschfeld co-wrote and acted in the 1919 film Anders als die Andern ('Different From the Others'), in which Conrad Veidt played one of the first homosexual characters ever written for cinema.

In Germany, however, despite more than fifty years of scientific research, legal discrimination against homosexuals continues unabated... May justice soon prevail over injustice in this area, science conquer superstition, love achieve victory over hatred!

"[58] The reference to Émile Zola's role in the Dreyfus affair was intended to draw a parallel between homophobia and anti-Semitism, while Hirschfeld's repeated use of the word "us" was an implied admission of his own homosexuality.

[58] The anti-suicide message of Anders als die Andern reflected Hirschfeld's interest in the subject of the high suicide rate among homosexuals, and was intended to give hope to gay audiences.

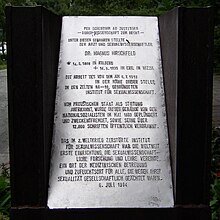

[58] Under the more liberal atmosphere of the newly founded Weimar Republic, Hirschfeld purchased a villa not far from the Reichstag building in Berlin for his new Institut für Sexualwissenschaft ('Institute of Sexual Research'), which opened on 6 July 1919.

Hirschfeld biographer Ralf Dose notes, for instance, that "the figure of 'Dorchen' in Rosa von Praunheim's film The Einstein of Sex is complete fiction.

Under the rule of Brüning as Chancellor and that of his successor, Franz von Papen, the state became increasingly hostile toward gay rights campaigners such as Hirschfeld, who began to spend more time abroad.

[70] The Milwaukee Sentinel was part of the newspaper chain owned by William Randolph Hearst, which initially promoted Hirschfeld in America, reflecting the old adage that "sex sells".

In the interview with Viereck, Hirschfeld was presented as the wise "European expert on romantic love" who had come to teach heterosexual American men how to enjoy sex, claiming there was a close connection between sexual and emotional intimacy.

[71] At least part of the reason for his "straight turn" was financial; a Dutch firm had been marketing Titus Pearls (Titus-Perlen) pills, which were presented in Europe as a cure for "scattered nerves" and in the United States as an aphrodisiac, and had been using Hirschfeld's endorsement to help with advertising campaign there.

[72] Most Americans knew of Hirschfeld only as a "world-known authority on sex" who had endorsed the Titus Pearls pills, which were alleged to improve orgasms for both men and women.

[72] At times, Hirschfeld returned to his European message, when he planned to deliver a talk at the bohemian Dill Pickle Club in Chicago on "homosexuality with beautiful revealing pictures", which was banned by the city as indecent.

[75] In Japan, Hirchfeld again tailored his speeches to local tastes, saying nothing about gay rights, and merely argued that a greater frankness about sexual matters would prevent venereal diseases.

[77] Shortly before leaving Tokyo for China, Hirschfeld expressed the hope that his host and translator, Wilhelm Grundert, the director of the German–Japanese Cultural Institute, be made a professor at a German university.

[82] Hirschfeld, who was fluent in English, made a point of quoting from the articles written by W. T. Stead in The Pall Mall Gazette in 1885, exposing rampant child prostitution in London as proving that sexuality in Britain could also be brutal and perverted: a matter which, he noted, did not interest Mayo in the slightest.

[85] In March 1932, Hirschfeld arrived in Athens, where he told journalists that, regardless of whether Hindenburg or Hitler won the presidential election that month, he probably would not return to Germany, as both men were equally homophobic.

A conservative Catholic who had long been a vocal critic of homosexuality, Papen ordered the Prussian police to start enforcing Paragraph 175 and to crack down in general on "sexual immorality" in Prussia.

On his 65th birthday, 14 May 1933, Hirschfeld arrived in Paris, where he lived in a luxury apartment building on 24 Avenue Charles Floquet, facing the Champ de Mars.

[95] He added that, in the 19th century, an ideology that divided all of humanity into biologically different races – white, black, yellow, brown, and red – as devised by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach – served as a way of turning prejudices into a "universal truth", apparently validated by science.

In the book's preface, he described his hopes for his new life in France: In search of sanctuary, I have found my way to that country, the nobility of whose traditions, and whose ever-present charm, have already been as balm to my soul.