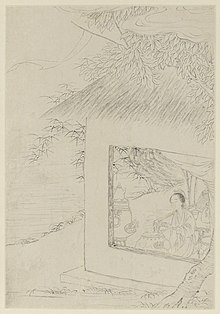

Magu (deity)

Stories in Chinese literature describe Magu as a beautiful young woman with long birdlike fingernails, while early myths associate her with caves.

[citation needed] While Magu folktales are familiar in East Asia, the sociologist Wolfram Eberhard was the first Western scholar to analyze them.

Based on references in Chinese texts, Eberhard proposed two centers for the Magu cult, in the present-day provinces of Jiangxi and Hubei.

Evidence for an "original cultic center"[8] near Nancheng (南城) county in southwestern Jiangxi includes several place names, and, among them, two mountains'.

"[8] Scholar Robert Campany provides details of Magu mythology in his annotated translation of Ge Hong's Traditions of Divine Transcendents (Shenxian zhuan (神仙傳), ca.

Wang was supposedly a Confucianist scholar who quit his official post during the reign (146–168 CE) of Emperor Huan of Han and went into the mountains to become a Daoist xian.

Later, while traveling in Wu (modern Zhejiang), Wang met Cai Jing 蔡經, whose physiognomy indicated he was destined to become an immortal, and taught him the basic techniques.

After Wang and his celestial entourage arrived on the auspicious "double-seven" day, he invited Magu to join their celebration because "It has been a long time since you were in the human realm."

After apologizing that she would be delayed owing to an appointment at Penglai Mountain (a legendary island in the Eastern Sea, where the elixir of immortality grows), Ma arrived four hours later.

[12] When Magu was introduced to the women in Cai's family, she transformed some rice into pearls as a trick to avoid the unclean influences of a recent childbirth.

Then Wang presented Cai's family with a strong liquor from "the celestial kitchens", and warned that it was "unfit for drinking by ordinary people".

Canghai sangtian (滄海桑田 "blue ocean [turns to] mulberry fields") means "great changes over the course of time"; Needham says early Daoists observed seashells in mountainous rocks and recognized the vast scale of geologic transformations.

[14] The Lieyi zhuan (列異傳 "Arrayed Marvels", late 2nd or early 3rd century), attributed to Cao Pi (187–226 CE) has three stories about Wang Fangping.

Here, Cai Jing's home is located in Dongyang; he is not whipped but rather flung to the ground, his eyes running blood; and Maid Ma herself, identified as "a divine transcendent" (shenxian), is the one who reads his thoughts and does the punishing.

[16] The Yiyuan (異苑 "Garden of Marvels", early 5th century), by Liu Jingshu (劉敬叔), records a story about Meigu (梅姑 "Plum Maid") or Magu, and suggests her cult originated during the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE).

[6]Campany reads this legend to describe founding a temple, probably on Lake Gongting, and translates these "shaman" and "shrine" references in the future tense.

She captured a strange beast resembling a sea turtle and a serpent, and ate it with her companion Hua Ben (華本 "Flower Root").

Campany concludes: This story hints at an even older stratum of legend behind the Maid Ma cult: like other territorial gods known to Chinese religious history, she may have begun as a theriomorphic deity (perhaps snake-headed) who gradually metamorphosed into a human being and finally – the process culminating in Ge Hong's Traditions narrative – into a full-fledged transcendent.

"[2] The historian and sinologist Joseph Needham connected myths about Magu "the Hemp Damsel" with early Daoist religious usages of cannabis.

Tao Hongjing (456–536 CE), who edited the official Shangqing canon, also recorded, "Hemp-seeds ([mabo] 麻勃) are very little used in medicine, but the magician-technicians ([shujia] 術家) say that if one consumes them with ginseng it will give one preternatural knowledge of events in the future.

"[22] Needham concluded, Thus all in all there is much reason for thinking that the ancient Taoists experimented systematically with hallucinogenic smokes, using techniques which arose directly out of liturgical observance.

[5]Mago appears in a number of sources, including the academically disputed Budoji, folklore, place-names, art, classical literature, folksongs, shamanic songs (muga), historical and religious texts, and miscellaneous data.

In one story, Mago is portrayed as the cosmic weaver who descends in the region (Jinhae, South Gyeongsang) to herald the season of weaving hemp.