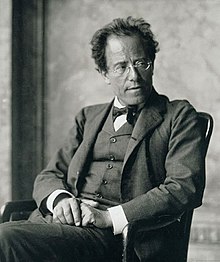

Gustav Mahler

While in his lifetime his status as a conductor was established beyond question, his own music gained wide popularity only after periods of relative neglect, which included a ban on its performance in much of Europe during the Nazi era.

[4] Jihlava was then a thriving commercial city of 20,000 people, in which Gustav was introduced to music through the street songs of the day, through dance tunes, folk melodies and the trumpet calls and marches of the local military band.

Mahler sought to express his feelings in music: with the help of a friend, Josef Steiner, he began work on an opera, Herzog Ernst von Schwaben ("Duke Ernest of Swabia"), as a memorial to his lost brother.

[16] Mahler developed interests in German philosophy, and was introduced by his friend Siegfried Lipiner to the works of Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Nietzsche, Gustav Fechner and Hermann Lotze.

Mahler's biographer Jonathan Carr says that the composer's head was "not only full of the sound of Bohemian bands, trumpet calls and marches, Bruckner chorales and Schubert sonatas.

[24] He enjoyed early success presenting works by Mozart and Wagner, composers with whom he would be particularly associated for the rest of his career,[22] but his individualistic and increasingly autocratic conducting style led to friction, and a falling out with his more experienced fellow-conductor, Ludwig Slansky.

[28] However, Mahler had secretly been invited by Angelo Neumann in Prague (and accepted the offer) to conduct the premiere there of "his" Die drei Pintos, and later also a production of Der Barbier von Bagdad by Peter Cornelius.

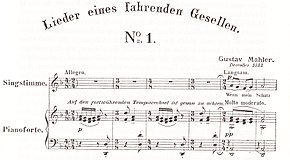

Between his Laibach and Olmütz appointments he worked on settings of verses by Richard Leander and Tirso de Molina, later collected as Volume I of Lieder und Gesänge ("Songs and Airs").

[34] Aware of the delicate situation, Mahler moved cautiously; he delayed his first appearance on the conductor's stand until January 1889, when he conducted Hungarian-language performances of Wagner's Das Rheingold and Die Walküre to initial public acclaim.

[35] However, his early successes faded when plans to stage the remainder of the Ring cycle and other German operas were frustrated by a renascent conservative faction which favoured a more traditional "Hungarian" programme.

[35] In search of non-German operas to extend the repertory, Mahler visited in spring 1890 Italy where among the works he discovered was Mascagni's recent sensation Cavalleria rusticana (Budapest premiere on 26 December 1890).

[34][38] In 1891, Hungary's move to the political right was reflected in the opera house when Beniczky on 1 February was replaced as intendant by Count Géza Zichy, a conservative aristocrat determined to assume artistic control over Mahler's head.

[42] Mahler's demanding rehearsal schedules led to predictable resentment from the singers and orchestra in whom, according to music writer Peter Franklin, the conductor "inspired hatred and respect in almost equal measure".

On 27 October 1893, at Hamburg's Konzerthaus Ludwig, Mahler conducted a revised version of his First Symphony; still in its original five-movement form, it was presented as a Tondichtung (tone poem) under the descriptive name "Titan".

[62][n 4] The collaboration between Mahler and Roller created more than 20 celebrated productions of, among other operas, Beethoven's Fidelio, Gluck's Iphigénie en Aulide and Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro.

[94] Immediately following this devastating loss, Mahler learned that his heart was defective, a diagnosis subsequently confirmed by a Vienna specialist, who ordered a curtailment of all forms of vigorous exercise.

The occasion was a triumph—"easily Mahler's biggest lifetime success", according to Carr[104]—but it was overshadowed by the composer's discovery, before the event, that Alma had begun an affair with the young architect Walter Gropius.

On 21 February 1911, with a temperature of 40 °C (104 °F), Mahler insisted on fulfilling an engagement at Carnegie Hall, with a program of mainly new Italian music, including the world premiere of Busoni's Berceuse élégiaque.

Mahler did not give up hope; he talked of resuming the concert season, and took a keen interest when one of Alma's compositions was sung at a public recital by the soprano Frances Alda, on 3 March.

[116] In London, The Times obituary said his conducting was "more accomplished than that of any man save Richter", and that his symphonies were "undoubtedly interesting in their union of modern orchestral richness with a melodic simplicity that often approached banality", though it was too early to judge their ultimate worth.

"[144] True to this belief, Mahler drew material from many sources into his songs and symphonic works: bird calls and cow-bells to evoke nature and the countryside, bugle fanfares, street melodies and country dances to summon the lost world of his childhood.

Amid all this is Mahler's particular hallmark—the constant intrusion of banality and absurdity into moments of deep seriousness, typified in the second movement of the Fifth Symphony when a trivial popular tune suddenly cuts into a solemn funeral march.

"[147] Franklin lists specific features which are basic to Mahler's style: extremes of volume, the use of off-stage ensembles, unconventional arrangement of orchestral forces, and frequent recourse to popular music and dance forms such as the ländler and the waltz.

[133] Musicologist Vladimír Karbusický maintains that the composer's Jewish roots had lasting effects on his creative output; he pinpoints the central part of the third movement of the First Symphony as the most characteristically "Yiddish" music in Mahler's work.

His many enemies in the city used the anti-Semitic and conservative press to denigrate almost every performance of a Mahler work;[155] thus the Third Symphony, a success in Krefeld in 1902, was treated in Vienna with critical scorn: "Anyone who has committed such a deed deserves a couple of years in prison.

[152] However, much American critical reaction in the 1920s was negative, despite a spirited effort by the young composer Aaron Copland to present Mahler as a progressive, 30 years ahead of his time and infinitely more inventive than Richard Strauss.

[161] An early proponent of Mahler's work in Britain was Adrian Boult, who as conductor of the City of Birmingham Orchestra performed the Fourth Symphony in 1926 and Das Lied von der Erde in 1930.

[163] The Hallé Orchestra brought Das Lied and the Ninth Symphony to Manchester in 1931; Sir Henry Wood staged the Eighth in London in 1930, and again in 1938 when the young Benjamin Britten found the performance "execrable" but was nevertheless impressed by the music.

[152] Harold Schonberg comments that "it is hard to think of a composer who arouses equal loyalty", adding that "a response of anything short of rapture to the Mahler symphonies will bring [to the critic] long letters of furious denunciation.

"[182] Mitchell highlights Britten's "marvellously keen, spare and independent writing for the wind in ... the first movement of the Cello Symphony of 1963 [which] clearly belongs to that order of dazzling transparency and instrumental emancipation which Mahler did so much to establish."