Thomas Mitchell (explorer)

The finished drawings were published by the London geographer James Wyld in 1841 under the title Atlas containing the principle battles, sieges and affairs of the Peninsular War.

[2] In this post he did much to improve the quality and accuracy of surveying – a vital task in a colony where huge tracts of land were being opened up and sold to new settlers.

[16] Around this time, a portrait of Mitchell was painted showing him in the uniform of Major of the 1st Rifle Brigade of the 95th Regiment, complete with whistle used to direct the movement of troops.

Mitchell formed an expedition consisting of himself, assistant surveyor George Boyle White and 15 convicts who were promised remission for good conduct.

Mitchell took 20 bullocks, three heavy drays, three light carts and nine horses to carry supplies, and set out on 24 November 1831 to investigate the claim.

On reaching Wollombi in the Hunter Valley, the local assistant surveyor, Heneage Finch, expressed a desire to join the expedition which Mitchell approved, provided he first obtain extra provisions and rendezvous later.

[18] The expedition continued northward, and having climbed the Liverpool Range on 5 December, they found an Aboriginal tribe who had fled from their home in the Hunter Valley and were suffering from what appeared to be smallpox.

Mitchell's party then headed north unguided but managed to reach the Gwydir River in mid-January where they found a small Aboriginal village of conical-roofed huts.

Aboriginal people approached the group laying down their spears and offering females to Mitchell's men in an apparent attempt at appeasement for the killings.

Months later, a search party of military mounted police commanded by Lieutenant Henry Zouch of the first division, discovered that Cunningham had been killed by four Wiradjuri men and his bones were found and buried at Currindine.

Here, on a high point of land which bore many Aboriginal grave sites, Mitchell decided to build a fort as he realised that they "had not asked permission to come there" and he needed a stockade for "stout resistance against any number of natives."

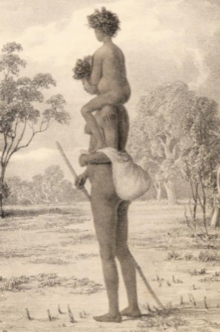

[20] They encountered many tribes as they headed south, with Mitchell documenting the agricultural practices of some, such as the harvesting of Panicum decompositum, and the large permanent dwellings of others.

[19] Just north of the Menindee Lakes, the expedition came across a large congregation of several tribes and Mitchell decided that continuing the exploration would be too dangerous.

After more than an hour, some members of the group returned reporting that a skirmish had occurred over the possession of a kettle and at least three Aboriginal people had been shot dead, including a woman and her child.

A Wiradjuri man named John Piper was also recruited and 23 convicts and ticket of leave men made up the rest of the party.

At this place they met with a large clan from which a number of people joined the expedition and gave vital information about waterholes, as the Lachlan was drying out.

According to the account given to a later enquiry by William Muirhead (bullock-driver and sergeant), Alexander Burnett (overseer) and Jemmy Piper (Aboriginal man accompanying the party): on 24 May Mitchell noticed that Barkindji tribesmen from the Darling River were gathering in large numbers, and by 27 May the hostile intentions of these men became known, when local Murray River people told Piper that the Barkindji were planning to kill Mitchell and his men.

[26] Mitchell wrote about the loss of life in his journal, describing the Barkindji as "treacherous savages", and detailing how his men had chased them away, "pursuing and shooting as many as they could".

Mitchell noted the local people's practice of making large nets that spanned above the river to catch waterfowl and also came across unusual animals such as the now extinct Southern pig-footed bandicoot.

They were guided by a local Aboriginal woman along part of the Nangeela (Glenelg River) with Mitchell constructing a fortified base on its banks which he named Fort O'Hare.

On 17 September, in order to speed his return, Mitchell split the party in two, taking 14 men with him and leaving the remainder with Stapylton to follow with the bullocks and drays.

[32] On 15 December 1845 Mitchell started from Boree near Orange with a large party of 32 people including Edmund Kennedy as second in command (later speared to death at Escape River near Cape York).

Near the Macquarie Marshes the harvesting of native millet by Aboriginal people to make bread was recorded and a local man named Yulliyally guided the group to the Barwon River.

Being a tributary of the Burdekin River, a waterway already visited by Ludwig Leichhardt on his expedition to Port Essington in 1845, Mitchell was dismayed to find that he was approaching ground already explored by Europeans.

By the time he arrived back in mid-1848, he had published his Journal of an Expedition into the Interior of Tropical Australia, in search of a route from Sydney to the Gulf of Carpentaria.

[2] He found it difficult to separate his roles of government employee and elected member of the legislature, and after only five months he resigned from the Legislative Council.

'[8][42] He travelled west during winter to visit the Ophir gold diggings, accompanied by his son, Roderick, and Samuel Stutchbury the government geologist.

The results of this trial were considered satisfactory, the ship's progress being calculated on two runs at 10 and a little over 12 knots,[46] and Sir Thomas Mitchell took his Invention to England.

His family enjoyed a privileged upbringing, and Blanche Mitchell, his youngest daughter, recorded her daily activities and social life in childhood diaries and notebooks.

[57][5] Newspapers of the day commented:"For a period of twenty-eight years Sir Thomas Mitchell had served the Colony, much of that service having been exceedingly arduous and difficult.