Makassarese language

It is a member of the South Sulawesi group of the Austronesian language family, and thus closely related to, among others, Buginese, also known as Bugis.

[4] However, etymostatistical analysis and functor statistics conducted by linguist Ülo Sirk shows a higher vocabulary similarity percentage (≥ 60%) between Makassarese and other South Sulawesi languages.

[5] These quantitative findings support qualitative analyses that place Makassarese as part of the South Sulawesi language family.

[8][7][9] The main differences among these varieties within the Makassar group lie in vocabulary; their grammatical structures are generally quite similar.

[10] According to a demographic study based on the 2010 census data, about 1.87 million Indonesians over the age of five speak Makassarese as their mother tongue.

Some urban Makassar residents, especially those from the middle class or with multiethnic backgrounds, also use Indonesian as the primary language in their households.

Some instances of these might result from Proto-Malayo-Polynesian schwa phoneme *ə (now merged into a), which geminated the following consonant (*bəli > *bəlli > balli 'to buy, price' (compare Indonesian beli), contrasting with bali 'to oppose').

The voiceless plosive phonemes /p t k/ are generally pronounced with slight aspiration (a flow of air), as in the words katte [ˈkat̪.t̪ʰɛ] 'we', lampa [ˈlam.pʰa] 'go', and kana [ˈkʰa.nã] 'say'.

The phonemes /b/ and /d/ have implosive allophones [ɓ] and [ɗ], especially in word-initial positions, such as in balu [ˈɓa.lu] 'widow', and after the sound [ʔ], as in aʼdoleng [aʔ.ˈɗo.lẽŋ] 'to let hang'.

The palatal phoneme /c/ can be realized as an affricate (a stop sound with a release of fricative) [cç] or even [tʃ].

[23] In syllables located at the end of a morpheme, C2 can be filled by a stop (T) or a nasal (N), the pronunciation of which is determined by assimilation rules.

This analysis is based on the fact that Makassarese distinguishes between the sequences [nr], [ʔr], and [rr] across syllables.

However, longer words can be formed due to the agglutinative nature of Makassarese and the highly productive reduplication process.

[34] Other morphemes counted as part of the stress-bearing unit include the affixal clitic,[a] marking possession, as in the word tedóng=ku (buffalo=1.POSS) 'my buffalo'.

[37][38] A word can have stress on the preantepenultimate (fourth-last) syllable if a two-syllable enclitic combination such as =mako (PFV =ma, 2 =ko) is appended; e.g., náiʼmako 'go up!

[29][30][28] However, the addition of suffixes -ang and -i will remove this epenthetic syllable and move the stress to the penultimate position, as in the word lapísi 'to layer'.

Adding the possessive clitic suffix also shifts the stress to the penultimate position but does not remove this epenthetic syllable, as in the word botolóʼna 'its bottle'.

The first person plural pronoun series ku= is commonly used to refer to the first person plural in modern Makassar; pronouns kambe and possessive marker =mang are considered archaic, while the enclitic =kang can only appear in combination with clitic markers of modality and aspect, such as =pakang (IPFV =pa, 1PL.EXCL =kang).

'[44]Nouns in Makassarese are a class of words that can function as arguments for a predicate, allowing them to be cross-referenced by pronominal clitics.

[50] Examples of compound words derived from these generic nouns are jeʼneʼ inung 'drinking water', tai bani 'wax, beeswax' (literal meaning: 'bee excrement'), and anaʼ baine 'daughter'.

[52] Derived nouns in Makassarese are formed through several productive morphological processes, such as reduplication and affixation with pa-, ka-, and -ang, either individually or in combination.

[53] The following table illustrates some common noun formation processes in Makassarese:[54][55] meanings or user botoroʼ 'gamble' → pabotoroʼ 'gambler' anjoʼjoʼ 'point' → panjoʼjoʼ 'index finger, pointer' angnganre 'eat' → pangnganreang 'plate' easily ADJ, inclined to be ADJ There are some exceptions to the general patterns described above.

[76] The components of noun phrases in the Makassarese can be categorized into three groups, namely 1) head, 2) specifier, and 3) modifier.

Texts written in the Serang script are relatively rare, and mostly appear in connection with Islam-related topics.

Parts of the Makassar Annals, the chronicles of the Gowa and Tallo' kingdoms, were also written using the Serang script.

[86] Given that Lontara script is also traditionally written without word breaks, a typical text often has many ambiguous portions which can often only be disambiguated through context.

As an illustration, Cummings and Jukes provide the following example to illustrate how the Lontara script can produce different meanings depending on how the reader cuts and fills in the ambiguous part: Without knowing the actual event to which the text may be referring, it can be impossible for first time readers to determine the "correct" reading of the above examples.

Even the most proficient readers may need to pause and re-interpret what they have read as new context is revealed in later portions of the same text.

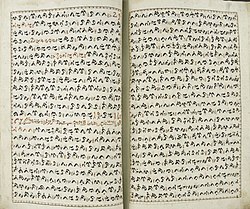

[89] After Islam arrived in 1605, and with Malay traders using the Arabic-based Jawi script, Makassarese could also be written using Arabic letters.

This was called 'serang' and was better at capturing the spoken language than the original Makassarese scripts because it could show consonants at the ends of syllables.