Constitution of Malaysia

[4] Constitutional Conference: A constitutional conference was held in London from 18 January to 6 February 1956 attended by a delegation from the Federation of Malaya, consisting of four representatives of the Rulers, the Chief Minister of the Federation (Tunku Abdul Rahman) and three other ministers, and also by the British High Commissioner in Malaya and his advisers.

It is expressly provided that work incidental to serving a sentence of imprisonment imposed by a court of law is not forced labour.

Clause 2 states: "Except as expressly authorised by this Constitution, there shall be no discrimination against citizens on the ground only of religion, race, descent, gender or place of birth in any law or in the appointment to any office or employment under a public authority or in the administration of any law relating to the acquisition, holding or disposition of property or the establishing or carrying on of any trade, business, profession, vocation or employment".

The exceptions expressly allowed under the Constitution includes the affirmative actions taken to protect the special position for the Malays of Peninsular Malaysia and the indigenous people of Sabah and Sarawak under Article 153.

Article 10 is a key provision of Part II of the Constitution, and has been regarded as "of paramount importance" by the judicial community in Malaysia.

These include the power to close roads, erect barriers, impose curfews, and to prohibit or regulate processions, meetings or assemblies of five persons or more.

[11] Another law which previously curtailed the freedoms of Article 10 is the Police Act 1967, which criminalised the gathering of three or more people in a public place without a licence.

The following are comments from the Malaysian Bar Council on the Peaceful Assembly Act: PA2011 appears to allow the police to decide what is a "street protest" and what is a "procession".

"Open letter from Lim Chee Wee, President of Malaysian Bar The Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984 gives the Home Affairs Minister the discretion to grant, suspend and revoke newspaper publishing permits.

Justice Raja Azlan Shah (later the Yang di-Pertuan Agong) once said: The right to free speech ceases at the point where it comes within the mischief of the Sedition Act.

[15]Suffian LP in the case of PP v Mark Koding [1983] 1 MLJ 111 said, in relation to the amendments to Sedition Act in 1970, after 13 May 1969 riots, which added citizenship, language, special position of bumiputras and sovereignty of rulers to the list of seditious matters: Malaysians with short memories and people living in mature and homogeneous democracies may wonder why in a democracy discussion of any issue and in Parliament of all places should be suppressed.

But Malaysians who remember what happened during 13 May 1969, and subsequent days are sadly aware that racial feelings are only too easily stirred up by constant harping on sensitive issues like language and it is to minimise racial explosions that the amendments were made [to the Sedition Act].Article 10(c)(1) guarantees the freedom of association subject only to restrictions imposed through any federal law on the grounds of national security, public order or morality or through any law relating to labour or education (Article 10(2)(c) and (3)).

In relation to the freedom of incumbent elected legislators to change their political parties, the Supreme Court of Malaysia in the Kelantan State Legislative Assembly v Nordin Salleh held that an "anti party-hopping" provision in the Kelantan State Constitution violates the right to freedom of association.

Such power may be exercised by him personally only in accordance with Cabinet advice (except where the Constitution allows him to act in his own discretion)(Art.

Under Article 71 and the 8th Schedule, all State Constitutions are required to have a provision similar to the above in relation to their respective Menteri Besar (Chief Minister) and Executive Council (Exco).

The Court held that (i) as the Perak State Constitution does not stipulate that the loss of confidence in a Menteri Besar can only be established through a vote in the assembly, then following the Privy Council's decision in Adegbenro v Akintola [1963] AC 614 and the High Court's decision in Dato Amir Kahar v Tun Mohd Said Keruak [1995] 1 CLJ 184, evidence of loss of confidence may be gathered from other sources and (ii) it is mandatory for a Menteri Besar to resign once he loses the confidence of the majority and if he refuses to do so then, following the decision in Dato Amir Kahar, he is deemed to have resigned.

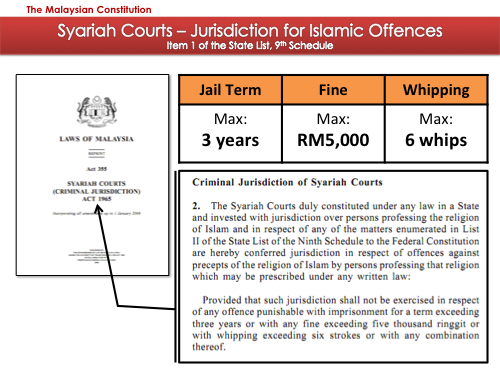

This exclusion of jurisdiction over Syariah matters is stipulated in Clause 1A of Article 121, which was added to the Constitution by Act A704, in force from 10 June 1988.

[19] Article 149 gives power to the Parliament to pass special laws to stop or prevent any actual or threatened action by a large body of persons which Parliament believes to be prejudicial to public order, promoting hostility between races, causing disaffection against the State, causing citizens to fear organised violence against them or property, or prejudicial to the functioning of any public service or supply.

This article permits the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, acting on Cabinet advice, to issue a Proclamation of Emergency and to govern by issuing ordinances that are not subject to judicial review if the Yang di-Pertuan Agong is satisfied that a grave emergency exists whereby the security, or the economic life, or public order in the Federation or any part thereof is threatened.

Article 153 stipulates that the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, acting on Cabinet advice, has the responsibility for safeguarding the special position of Malays and the indigenous peoples of Sabah and Sarawak, and the legitimate interests of all other communities.

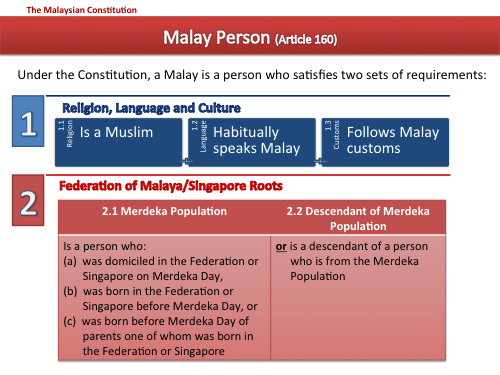

The term Bumiputra is commonly used to refer collectively to Malays and the indigenous peoples of Sabah and Sarawak, but it is not defined in the constitution.

The NEP aimed to eradicate poverty irrespective of race by expanding the economic pie so that the Chinese share of the economy would not be reduced in absolute terms but only relatively.

Clause (2) of this Article also states that only the Parliament has exclusive power to make laws to change or alter the boundaries of the federal capital.

Likewise, a non-Malay Malaysian who converts to Islam can lay claim to Bumiputra privileges, provided he meets the other conditions.

A higher education textbook conforming to the government Malaysian studies syllabus states: "This explains the fact that when a non-Malay embraces Islam, he is said to masuk Melayu (become a Malay).

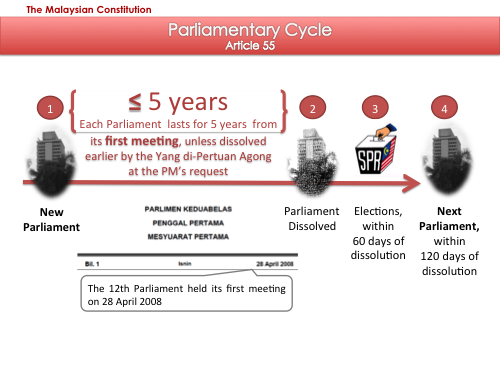

A person cannot be appointed as a senator for more than two terms (whether consecutive or not) and cannot simultaneously be a member of the Dewan Rakyat (and vice versa) (Art.

These include unsoundness of mind, bankruptcy, acquisition of foreign citizenship or conviction for an offence and sentenced to imprisonment for a term of not less than one year or to a "fine of not less than two thousand ringgit".

Anyone who was born inside Malaya between 31 August 1957 and 30 September 1962 are also automatically recognised as citizen under this Part, regardless of his parents' citizenship status.

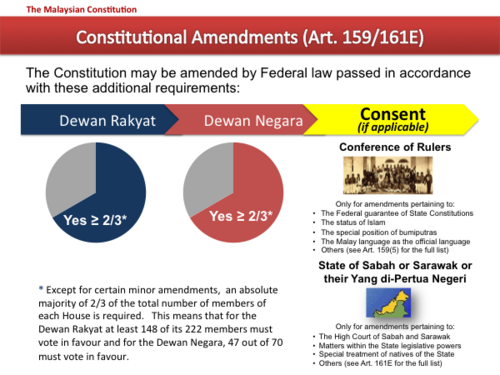

[39] This sentiment has been echoed by other legal scholars, who argue that important parts of the original Constitution, such as jus soli (right of birth) citizenship, a limitation on the variation of the number of electors in constituencies, and Parliamentary control of emergency powers have been so modified or altered by amendments that "the present Federal Constitution bears only a superficial resemblance to its original model".

This is so because the Malaysian Constitution lays downs very detailed provisions governing micro issues such as revenue from toddy shops, the number of High Court judges and the amount of federal grants to states.