Man in the Iron Mask

The Man in the Iron Mask (French: L'Homme au Masque de Fer; died 19 November 1703) was an unidentified prisoner of state during the reign of Louis XIV of France (1643–1715).

What little is known about the prisoner is based on contemporary documents uncovered during the 19th century, mainly some of the correspondence between Saint-Mars and his superiors in Paris, initially Louvois, Louis XIV's secretary of state for war.

This solution, however, was disproved in 1953 when previously unpublished family letters were discovered by another French historian, Georges Mongrédien, who concluded that the enigma remained unsolved owing to the lack of reliable historical documents about the prisoner's identity and the cause of his long incarceration.

A section of his novel The Vicomte of Bragelonne: Ten Years Later—the final installment of his D'Artagnan saga—features this prisoner, portrayed as Louis XIV's identical twin and forced to wear an iron mask.

In 1840, Dumas had first presented a review of the popular theories about the prisoner extant in his time in the chapter "L'homme au masque de fer", published in the eighth volume of his non-fiction Crimes Célèbres.

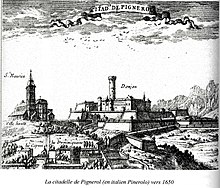

[3] Saint-Mars's other prisoners at Pignerol included Count Ercole Antonio Mattioli, an Italian diplomat who had been kidnapped and jailed for double-crossing the French over the purchase of the important fortress town of Casale on the Mantuan border.

In his letters to Louvois, Saint-Mars describes Dauger as a quiet man, giving no trouble, "disposed to the will of God and to the king", compared to his other prisoners, who were always complaining, constantly trying to escape, or simply mad.

[9] From this revealing letter, French historian Mongrédien concluded that Louvois was clearly anxious that any details about Dauger's former employment should not leak out if the King decided to relax the conditions of Fouquet's or Lauzun's incarceration.

[3] In the third edition (2004) of his book on the subject, French historian Jean-Christian Petitfils collated a list of 52 candidates, real or imagined, whose names had been either mentioned as rumours in contemporary documents, or proposed in printed works, between 1669 and 1992.

"[22][23][24][25][26] On 4 September 1687, the Nouvelles Écclésiastiques published a letter by Nicolas Fouquet's brother Louis, quoting a statement made by Saint-Mars: "All the people that one believes dead are not", a hint that the prisoner was the Duke of Beaufort.

[31][32][33][34] On 10 October 1711, King Louis XIV's sister-in-law, Elizabeth Charlotte, Princess Palatine, sent a letter to her aunt, Sophia, Electress of Hanover, stating that the prisoner had "two musketeers at his side to kill him if he removed his mask".

[39] Historians such as Mongrédien (1952) and Noone (1988), however, pointed out that the solution whereby Louis XIV is supposed to have had an illegitimate brother—whether older, twin, or younger—does not provide a credible explanation, for example, on how it would have been possible for Queen Anne of Austria to conceal a pregnancy throughout its full course and bear, then deliver, a child in secret.

"[42] In 1745, an anonymous writer published a book in Amsterdam, Mémoires pour servir à l'Histoire de la Perse, romanticising life at the French Court in the form of Persian history.

[60][61][62][63] The theme of an imagined elder brother of Louis XIV resurfaced in 1790, when French historian Pierre-Hubert Charpentier asserted that the prisoner was an illegitimate son of Anne of Austria and George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, supposedly born in 1626, two years before the latter's death.

Charpentier also stated that Voltaire had heard this version in Geneva, but chose to omit Buckingham's name when he began to develop his own variant of this theory in the first edition of The Age of Louis XIV (1751),[64] finally revealed in full in Questions sur l'Encyclopédie (1771).

[64] Many authors supported the theory of the prisoner being a twin brother of King Louis XIV: Michel de Cubières (1789), Jean-Louis Soulavie (1791), Las Cases (1816), Victor Hugo (1839), Alexandre Dumas (1840), Paul Lecointe (1847), and others.

[67] Pagnol's solution—combining earlier theories by Soulavie (1790),[70] Andrew Lang (1903),[71] Arthur Barnes (1908),[72] and Edith Carey (1924)[73]—speculates that this twin was born a few hours after Louis XIV and grew up on the Island of Jersey under the name James de la Cloche, believing himself to be an illegitimate son of Charles II.

[91] In 1908, Monsignor Arthur Barnes proposed that the prisoner was James de la Cloche, the alleged illegitimate son of the reluctant Protestant Charles II of England, who would have been his father's secret intermediary with the Catholic court of France.

However, in 1768, a writer named Saint-Foix claimed that another man was executed in his place and that Monmouth became the masked prisoner, it being in Louis XIV's interests to assist a fellow Catholic like James, who would not necessarily want to kill his own nephew.

The two men claimed that they had been provoked by the boy, who was drunk, but the fact that the killing took place close to where Louis XIV was staying at the time meant that this crime was deemed a personal affront to the king and, as a result, Dauger de Cavoye was forced to resign his commission.

[l][113] Wilkinson also supported the theory proposed by Petitfils—and by Jules Lair in 1890—that, as a valet (perhaps to Henrietta of England), this "Eustache" had committed some indiscretion which risked compromising the relations between Louis XIV and Charles II at a sensitive time during the negotiations of the Secret Treaty of Dover against the Dutch Republic.

[117] Many documents were stolen, or taken away by collectors, writers, lawyers, and even by Pierre Lubrowski, an attaché in the Russian embassy—who sold them to emperor Alexander I in 1805, when they were deposited at the Hermitage Palace—and many ended up dispersed throughout France and the rest of Europe.

On 16 July, the Electoral Assembly created a commission assigned to rescue the archives; on arrival at the fortress, they found that many boxes had been emptied or destroyed, leaving an enormous pile of papers in a complete state of disorder.

In 1840, François Ravaisson found a mass of old papers under the floor in his kitchen at the Arsenal library and realised he had rediscovered the archives of the Bastille, which required a further fifty years of laborious restoration; the documents were numbered, and a catalogue was compiled and published as the 20th century was about to dawn.

[124] In his historical essay published in 1965 and expanded in 1973, Marcel Pagnol praised a number of historians who consulted the archives with the goal of elucidating the enigma of the Man in the Iron Mask: Joseph Delort (1789–1847), Marius Topin (1838–1895), Théodore Iung (1833–1896), Maurice Duvivier (18?

[128] Giving full credit to Jules Lair for being the first to propose the candidacy of "Eustache Dauger" in 1890,[1] Mongrédien demonstrated that, among all the state prisoners who were ever in the care of Saint-Mars, only the one arrested under that pseudonym in 1669 could have died in the Bastille in 1703, and was therefore the only possible candidate for the man in the mask.

Although he also pointed out that no documents had yet been found that revealed either the real identity of this prisoner or the cause of his long incarceration, Mongrédien's work was significant in that it made it possible to eliminate all the candidates whose vital dates, or life circumstances for the period of 1669–1703, were already known to modern historians.

At the end of this review, Mongrédien mentioned being told that the Archives of the Ministry of Defense located at the Château de Vincennes still held unsorted and uncatalogued bundles of Louvois's correspondence.

[131] In addition to being the subject of scholarly research carried out by historians, the Man in the Iron Mask inspired literary works of fiction, many of which elaborate on the legend of the prisoner being a twin brother of Louis XIV, such as Alexandre Dumas's popular novel, Le Vicomte de Bragelonne (1850).

These films were all loosely adapted from Dumas' book The Vicomte de Bragelonne, where the prisoner was an identical twin of Louis XIV and made to wear an iron mask, per the legend created by Voltaire.