Manchester Arndale

The centre has a retail floorspace of just under 1,400,000 sq ft (130,000 m2) (not including Selfridges and Marks and Spencer department stores to which it is connected via a link bridge), making it Europe's third largest city-centre shopping mall.

[8][9][10][11][12] The city council recognised before the end of the Second World War that the area around Market Street was in need of redevelopment, and a plan was drawn up between 1942 and 1945 but no progress was made.

The corporation used compulsory purchase orders to speed redevelopment at the bomb-damaged Market Place (between the Corn Exchange and the Royal Exchange—the development has since been demolished), at the CIS buildings, and at Piccadilly.

[24] A public enquiry into the development started on 18 June 1968, with a submission that the existing street pattern, while historic, was "hopelessly inadequate for modern requirements".

[28] Manchester corporation compulsorily purchased a further 8 acres (3 ha) of property in 1970[29] using money raised by selling land outside the city bought for overspill housing.

[29] Shop Property predicted in 1971 that as "new buildings replace the existing dilapidated ones" the city centre would lose its Coronation Street image, and become "very attractive" to retailers.

Spring (in 1979) wrote of "monstrosities that have ousted the city's grand heritage of nineteenth century commercial and industrial architecture—if the recently completed mammoth and distinctly lavatorial Arndale Centre is anything to go by".

[37] Hamilton (in 2001) wrote that the area reflected Manchester's wealth and leadership in the middle of the 19th century, with buildings designed by leading UK architects.

By taking advantage of the change in height, the architects hoped to solve the problem of persuading shoppers to use the upper shopping area.

While the northern part had no anchor stores, the car park and bus station meant that foot traffic passed through the area, avoiding quiet spots.

The Guardian described it in 1978 as "an awful warning against thinking too big in Britain's cities" and "so castle-like in its outer strength that any passing medieval army would automatically besiege it rather than shop in it".

[44][57] At the official opening, one of its champions, Dame Kathleen Ollerenshaw, Mayor of Manchester, commented, "I didn't think it would look like that when I saw the balsa wood models".

[54] The tiles, made by Shaw Hathernware,[62] were a deep buff, variously described as "bile yellow",[63] "putty and chocolate" (some parts were brown)[12] and "vomit-coloured".

[66] "If there is some street or old shop in the market square, dock factory or warehouse, barn or garden wall which you have passed often and take for granted, do not expect to see it there next week.

Because it is not listed, because it is of 'no historical interest' the bulldozers will be in and part of your background will be gone forever" A backlash against comprehensive development was underway before the centre opened.

Amery and Dan Cruickshank's The Rape of Britain, with a foreword by John Betjeman, was published to mark European Architectural Heritage Year in 1975.

The book describes the redevelopment of about 20 towns under the heading "scenes of rape" and uses the Arndale as an example of "brutal obliteration" undertaken by "the mind that seriously believes that the centre of Manchester should look like a futuristic vision or a barbaric new city borrowed from Le Corbusier".

In the same year the pressure group Save Britain's Heritage was formed, in part to discourage the wholesale demolition of unremarkable industrial buildings in the north of England.

[71] Closures of shops and former textile warehouses comparable to those cleared for the Arndale meant the area quickly became run-down and in Bennison et al.'s eyes "almost fossilised".

A consequence of pent-up applications was that the adjacent newly created authorities of Salford and Trafford found themselves in a "prisoner's dilemma" over competing out-of-town schemes, at Barton Locks and Dumplington, broadly similar in size to the Arndale.

[70] A public enquiry (followed by action in the appeal court, and a case in the House of Lords) approved the Dumplington proposal (the Trafford Centre).

Artificial lighting and undistinguishable malls, with multiple dead ends and no obvious circular route, meant that shoppers were, in Morris's words, "bewildered by its maze-like intensity".

[91] By 1996 the Arndale was fully let, raised £20 m a year in rents,[92] was the seventh busiest shopping area in the UK in terms of sales,[93] and was visited by 750,000 people a week.

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) was blamed for the incidents, in which the devices were placed in soft furnishings during shopping hours.

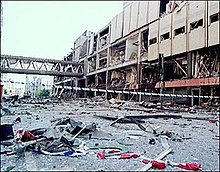

[98] At about 09:20 on Saturday morning, 15 June 1996, two men parked a 7+1⁄2-long-ton (7.6-tonne) lorry containing a 1,500 kg (3,300 lb) bomb on Corporation Street between Marks & Spencer and the Arndale.

The usual weekend population of shoppers was supplemented by football fans in town for the Russia v Germany match of UEFA Euro 1996, due to be staged on Sunday at Old Trafford.

The northern half was patched up, with buses originally stopping on Cannon Street itself before the bus station was eventually replaced by Shudehill Interchange in January 2006.

[102] Marks and Spencer, which was particularly badly damaged in the explosion, reopened in a separate building, linked to the main mall on the first floor by a glass footbridge which was designed by Stephen Hodder.

The new Winter Garden features stores such as a new Superdry (formerly HMV, Zavvi & Virgin Megastores), a Waterstone's bookshop, and a new single-level unit for the Arndale Market.

Halle Square was modernised, including new skylights,[105] but there is still a major difference in levels of natural light between the original malls and the northern extension, where the designers sought to maximise it.