Soviet invasion of Manchuria

It was the largest campaign of the 1945 Soviet–Japanese War, which resumed hostilities between the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the Empire of Japan after almost six years of peace.

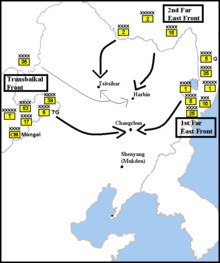

[21] At one minute past midnight Trans-Baikal time on 9 August 1945, the Soviets commenced their invasion simultaneously on three fronts to the east, west and north of Manchuria: Though the battle extended beyond the borders traditionally known as Manchuria—that is, the traditional lands of the Manchus—the coordinated and integrated invasions of Japan's northern territories has also been called the Battle of Manchuria.

At the Tehran Conference in November 1943, Stalin, Winston Churchill, and Franklin Roosevelt agreed that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan once Germany was defeated.

Stalin faced a dilemma: he wanted to avoid a war on two fronts at almost any cost, yet he also saw an opportunity to secure gains in the Far East on top of those he expected in Europe.

In return, Allied airmen held in the Soviet Union were usually transferred to camps near Iran or other Allied-controlled territory, from where they were typically allowed to "escape" after some period of time.

By early 1945 it had become apparent to the Japanese that the Soviets were preparing to invade Manchuria, though they correctly calculated that they were unlikely to attack prior to Germany's defeat.

At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, Stalin secured Roosevelt's acceptance of Soviet expansion in the Far East, in return for agreeing to enter the Pacific war within two or three months after the defeat of Germany.

The terms of the Pact required a notification of expiry 12 months ahead of time, so on 5 April 1945 the Soviets ostensibly obliged, informing the Japanese that they did not wish to renew the treaty.

[30] Germany surrendered just after midnight Moscow time on 9 May 1945, meaning that if the Soviets were to honour the agreement at Yalta, they would need to enter the war with Japan by 9 August.

Since Yalta, they had repeatedly tried to convince the Soviets to extend the Neutrality Pact, as well as attempting to enlist them to mediate peace negotiations with the Western Allies.

[30] One of the goals of Admiral Baron Suzuki's cabinet upon taking office in April was to try to secure any peace terms whatsoever short of unconditional surrender.

[31] In late June, they once again approached the Soviets, inviting them to mediate with the Western Allies in support of Japan, providing them with specific proposals.

On 26 July the conference produced the Potsdam Declaration whereby Churchill, Harry S. Truman and Chiang Kai-shek demanded Japan's unconditional surrender.

[16] They had estimated that an attack was not likely before the spring of 1946, but the Stavka had in fact been planning for a mid-August offensive, successfully concealing the buildup of a force of 90 divisions.

[2] These forces had as their objectives firstly to secure Mukden (present day Shenyang), then to meet troops of the 1st Far Eastern Front at the Changchun area in south central Manchuria,[1] and in doing so finish the pincer movement.

[1] The front also included the 88th Separate Rifle Brigade, composed of Chinese and Korean guerrillas of the Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army who had retreated into the USSR in the beginning of the 1940s.

The unit, led by Zhou Baozhong, was set to participate in the invasion for use in sabotage and reconnaissance missions, but was considered too valuable to be sent into the battlefield.

They were thus withheld from participating in combat and instead used for leadership and administrative positions for district offices and police stations in the liberated areas during the subsequent occupation.

[33] The Korean battalion of the brigade (including future leader of the DPRK, Kim Il Sung) were also sent to assist in the following occupation of Northern Korea as part of the 1st Far Eastern Front.

[35] However, the Kwantung Army was far below its authorized strength; most of its heavy equipment and all of its best military units had transferred to the Pacific Theater over the previous three years to contend with the advance of American forces.

By 1945 the Kwantung Army contained a large number of raw recruits and conscripts, with generally obsolete, light, or otherwise limited equipment.

The operation was carried out as a classic double pincer movement over an area the size of the entire Western European theatre of World War II.

The Kwantung Army commanders were engaged in a planning exercise at the time of the invasion, and were away from their forces for the first eighteen hours of conflict.

However, the Kwantung Army had a formidable reputation as fierce and relentless fighters, and even though understrength and unprepared, put up strong resistance at the town of Hailar which tied down some of the Soviet forces.

After a week of fighting, during which time Soviet forces had penetrated deep into Manchukuo, Japan's Emperor Hirohito recorded the Gyokuon-hōsō which was broadcast on radio to the Japanese nation on 15 August 1945.

It made no direct reference to a surrender of Japan, instead stating that the government had been instructed to accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration fully.

The land advance was stopped a good distance short of the Yalu River, the start of the Korean Peninsula, when even aerial supply became unavailable.

[57] According to Soviet historian Vyacheslav Zimonin, many Japanese settlers committed mass suicide as the Red Army approached.

[59][68] Konstantin Asmolov of the Center for Korean Research of the Russian Academy of Sciences dismisses Western accounts of Soviet violence against civilians in the Far East as exaggeration and rumor and contends that accusations of mass crimes by the Red Army inappropriately extrapolate isolated incidents regarding the nearly 2,000,000 Soviet troops in the Far East into mass crimes.

Another group of Japanese women that were with Ikeda Hiroko that on 15 August tried to flee to Harbin but returned to their settlements were raped by Soviet soldiers.