Manetho

Manetho (/ˈmænɪθoʊ/; Koinē Greek: Μανέθων Manéthōn, gen.: Μανέθωνος) is believed to have been an Egyptian priest from Sebennytos (Coptic: Ϫⲉⲙⲛⲟⲩϯ[2]) who lived in the Ptolemaic Kingdom in the early third century BC, during the Hellenistic period.

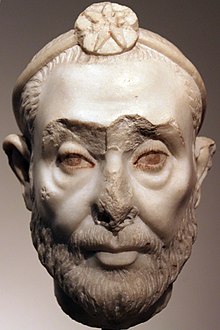

In the Greek language, the earliest fragments (the inscription of uncertain date on the base of a marble bust from the temple of Serapis at Carthage[4] and the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus of the 1st century AD) wrote his name as Μανέθων Manethōn, so the Latinised rendering of his name here is given as Manetho.

[citation needed] Although no sources for the dates of his life and death remain, Manetho is associated with the reign of Ptolemy I Soter (323–283 BC) by Plutarch (c. 46–120 AD), while George Syncellus links Manetho directly with Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285–246 BC).

Although the historicity of Manetho of Sebennytus was taken for granted by Josephus and later authors, the question as to whether he existed remains problematic.

Although the topics he supposedly wrote about dealt with Egyptian matters, he is said to have written exclusively in the Greek language for a Greek-speaking audience.

Other literary works attributed to him include Against Herodotus, The Sacred Book, On Antiquity and Religion, On Festivals, On the Preparation of Kyphi, and the Digest of Physics.

The gap is even larger for the other works attributed to Manetho such as The Sacred Book that is mentioned for the very first time by Eusebius in the fourth century AD.

Serapis was a Greco-Macedonian version of the Egyptian cult, probably started after Alexander the Great's establishment of Alexandria in Egypt.

Two English translations of the fragments of Manetho's Aegyptiaca have been published: by William Gillan Waddell in 1940,[8] and by Gerald P. Verbrugghe and John Moore Wickersham in 2001.

During this period, disputes raged concerning the oldest civilizations, and so Manetho's account was probably excerpted during this time for use in this argument with significant alterations.

We do not know when this might have occurred, but scholars [citation needed] specify a terminus ante quem at the first century AD, when Josephus began writing.

The earliest surviving attestation to Manetho is that of Contra Apionem ("Against Apion") by Flavius Josephus, nearly four centuries after Aegyptiaca was composed.

Other significant fragments include Malalas's Chronographia and the Excerpta Latina Barbari, a bad translation of a Greek chronology.

Josephus records him admitting to using "nameless oral tradition" (1.105) and "myths and legends" (1.229) for his account, and there is no reason to doubt this, as admissions of this type were common among historians of that era.

He must have been familiar with Herodotus, and in some cases, he even attempted to synchronize Egyptian history with Greek (for example, equating King Memnon with Amenophis, and Armesis with Danaos).

This suggests he was also familiar with the Greek Epic Cycle (for which the Ethiopian Memnon is slain by Achilles during the Trojan War) and the history of Argos (in Aeschylus's Suppliants).

At the behest of Ptolemy Philadelphus (266–228 BC), Manetho copied down a list of eight successive Persian kings, beginning with Cambyses, the son of Cyrus the Great.

This important anecdote is supplied by Herodotus who wrote the Magian ruled Persia for 7 months after the death of Cambyses.

Seti and Ramesses did not wish to make offerings to Akhenaten, Tutankhamen, or Hatshepsut, and that is why they are omitted, not because their existence was unknown or deliberately ignored in a broader historical sense.

For this reason, the Pharaonic king-lists were generally wrong for Manetho's purposes, and we should commend Manetho for not basing his account on them (2000:105).These large stelae stand in contrast to the Turin Royal Canon (such as Saqqara, contemporaneous with Ramesses II), written in hieratic script.

Verbrugghe and Wickersham suggest that a comprehensive list such as this would be necessary for a government office "to date contracts, leases, debts, titles, and other instruments (2000:106)" and so could not have been selective in the way the king-lists in temples were.

The Middle and Upper Egyptian kings did not have any effect upon this specific region of the delta; hence their exclusion from Manetho's king-list.

However, because of the simplicity with which Manetho transcribed long names (see above), they were preferred until original king-lists began to be uncovered in Egyptian sites, translated, and corroborated.

The Second Intermediate Period was of particular interest to Josephus, where he equated the Hyksos or "shepherd-kings" as the ancient Israelites who eventually made their way out of Egypt (Apion 1.82–92).

Most of the ancient witnesses group Manetho together with Berossos, and treat the pair as similar in intent, and it is not a coincidence that those who preserved the bulk of their writing are largely the same (Josephus, Africanus, Eusebius, and Syncellus).

Syncellus rejected both Manetho's and Berossos' incredible time-spans, as well as the efforts of other commentators to harmonise their numbers with the Bible.

If such were the case, Aegyptiaca was a failure, since Herodotus' Histories continued to provide the standard account in the Hellenistic world.

Syncellus similarly recognised its importance when recording Eusebius and Africanus, and even provided a separate witness from the Book of Sothis.

The French explorer and Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion reportedly held a copy of Manetho's lists in one hand as he attempted to decipher the hieroglyphs he encountered.

Manetho's Aegyptiaca has been cited as a source for early antisemitic ideas because of his account of Exodus, in which he portrays the Jewish people as forming from a group of lepers and shepherds who were expelled from Egypt and later conquered it, was repeated by later ancient authors such as Posidonius of Apamea, Lysimachus, Chaeremon, Apion, and Tacitus.