Synthetic diamond

In the 1940s, systematic research of diamond creation began in the United States, Sweden and the Soviet Union, which culminated in the first reproducible synthesis in 1953.

Electronic applications of synthetic diamond are being developed, including high-power switches at power stations, high-frequency field-effect transistors and light-emitting diodes.

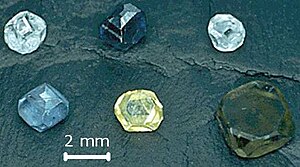

[4] Both CVD and HPHT diamonds can be cut into gems, and various colors can be produced: clear white, yellow, brown, blue, green and orange.

In the early stages of diamond synthesis, the founding figure of modern chemistry, Antoine Lavoisier, played a significant role.

A prominent scientist and engineer known for his invention of the steam turbine, he spent about 40 years (1882–1922) and a considerable part of his fortune trying to reproduce the experiments of Moissan and Hannay, but also adapted processes of his own.

[24] Parsons was known for his painstakingly accurate approach and methodical record keeping; all his resulting samples were preserved for further analysis by an independent party.

[26] However, in 1928, he authorized Dr. C. H. Desch to publish an article[27] in which he stated his belief that no synthetic diamonds (including those of Moissan and others) had been produced up to that date.

[22] The first known (but initially not reported) diamond synthesis was achieved on February 16, 1953, in Stockholm by ASEA (Allmänna Svenska Elektriska Aktiebolaget), Sweden's major electrical equipment manufacturing company.

His breakthrough came when he used a press with a hardened steel toroidal "belt" strained to its elastic limit wrapped around the sample, producing pressures above 10 GPa (1,500,000 psi) and temperatures above 2,000 °C (3,630 °F).

[40] In the 1950s, research started in the Soviet Union and the US on the growth of diamond by pyrolysis of hydrocarbon gases at the relatively low temperature of 800 °C (1,470 °F).

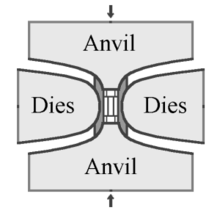

[54] The original GE invention by Tracy Hall uses the belt press wherein the upper and lower anvils supply the pressure load to a cylindrical inner cell.

The gases are ionized into chemically active radicals in the growth chamber using microwave power, a hot filament, an arc discharge, a welding torch, a laser, an electron beam, or other means.

Being immersed in water, the chamber cools rapidly after the explosion, suppressing conversion of newly produced diamond into more stable graphite.

[64] The product is always rich in graphite and other non-diamond carbon forms, and requires prolonged boiling in hot nitric acid (about 1 day at 250 °C (482 °F)) to dissolve them.

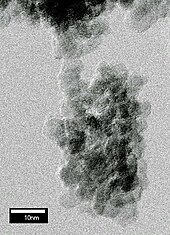

[65] Micron-sized diamond crystals can be synthesized from a suspension of graphite in organic liquid at atmospheric pressure and room temperature using ultrasonic cavitation.

[53][66] In 2024, scientists announced a method that utilizes injecting methane and hydrogen gases onto a liquid metal alloy of gallium, iron, nickel and silicon (77.25/11.00/11.00/0.25 ratio) at approximately 1,025 °C to crystallize diamond at 1 atmosphere of pressure.

Polycrystalline diamond (PCD) consists of numerous small grains, which are easily seen by the naked eye through strong light absorption and scattering; it is unsuitable for gems and is used for industrial applications such as mining and cutting tools.

Growth processes of synthetic diamond, using solvent-catalysts, generally lead to formation of a number of impurity-related complex centers, involving transition metal atoms (such as nickel, cobalt or iron), which affect the electronic properties of the material.

[79] Unlike most electrical insulators, pure diamond is an excellent conductor of heat because of the strong covalent bonding within the crystal.

Common industrial applications of this ability include diamond-tipped drill bits and saws, and the use of diamond powder as an abrasive.

Those synthetic polycrystalline diamond windows are shaped as disks of large diameters (about 10 cm for gyrotrons) and small thicknesses (to reduce absorption) and can only be produced with the CVD technique.

[90] Recent advances in the HPHT and CVD synthesis techniques have improved the purity and crystallographic structure perfection of single-crystalline diamond enough to replace silicon as a diffraction grating and window material in high-power radiation sources, such as synchrotrons.

Since these elements contain one more or one fewer valence electron than carbon, they turn synthetic diamond into p-type or n-type semiconductor.

While no diamond transistors have yet been successfully integrated into commercial electronics, they are promising for use in exceptionally high-power situations and hostile non-oxidizing environments.

[106] In addition, diamonds can be used to detect redox reactions that cannot ordinarily be studied and in some cases degrade redox-reactive organic contaminants in water supplies.

[120] As of 2017, synthetic diamonds sold as jewelry were typically selling for 15–20% less than natural equivalents; the relative price was expected to decline further as production economics improved.

The drop was attributed largely to improvement in speed of laboratory growing of diamonds from weeks (and billions of years for natural stones) to hours.

The DiamondView tester from De Beers uses UV fluorescence to detect trace impurities of nitrogen, nickel, or other metals in HPHT or CVD diamonds.

Several laboratories, including GIA, IGI and GSI, inscribe every lab-grown diamond they certify with a laser inscription invisible to the naked eye that can be seen at ten times magnification.

Consumer demand for synthetic diamonds has been increasing, albeit from a small base, as customers look for ethically sound and cheaper stones.