Byzantine dress

A different border or trimming round the edges was very common, and many single stripes down the body or around the upper arm are seen, often denoting class or rank.

The scaramangion was a riding-coat of Persian origin, opening down the front and normally coming to the mid-thigh, although these are recorded as being worn by Emperors, when they seem to become much longer.

[2] Some manual workers, probably slaves, are shown continuing to wear, at least in summer, the basic Roman slip costume which was effectively two rectangles sewn together at the shoulders and below the arm.

A great variety of footwear is found, with sandals, slippers and boots to the mid-calf all common in manuscript illustrations and excavated finds, where many are decorated in various ways.

It is assumed that Byzantine women outside court circles went well wrapped up in public, and were relatively restricted in their movements outside the house; they are rarely depicted in art.

As in Graeco-Roman times, purple was reserved for the royal family; other colours in various contexts conveyed information as to class and clerical or government rank.

A donor figure in the same church, the Grand Logothete Theodore Metochites, who ran the legal system and finances of the Empire, wears an even larger hat, which he keeps on whilst kneeling before Christ (see Gallery).

This was perhaps related to the very elegant hat with a very high-domed peak, and a sharply turned-up brim coming far forward in an acute triangle to a sharp point (left), that was drawn by Italian artists when the Emperor John VIII Palaiologos went to Florence and the Council of Ferrara in 1438 in the last days of the Empire.

The distinctive garments of the Emperors (often there were two at a time) and Empresses were the crown and the heavily jewelled Imperial loros or pallium, that developed from the trabea triumphalis, a ceremonial coloured version of the Roman toga worn by Consuls (during the reign of Justinian I Consulship became part of the imperial status), and worn by the Emperor and Empress as a quasi-ecclesiastical garment.

Apart from jewels and embroidery, small enamelled plaques were sewn into the clothes; the dress of Manuel I Comnenus was described as being like a meadow covered with flowers.

[23] The royal daily robe was a simpler and more idealized regalia of the various Hellenistic kings, depicted in various frescoes and miniatures, which featured the emperor in a simple "chiton" robe, a "chlamys" of various sizes, a royal diadem and the imperial boots Tzangion of which elaborated examples are evidenced in imperial works such as the Paris psalter or the David plates, idealizing the concept of philanthropy and beneficence as the main roles of the perfect Hellenistic and Byzantine monarch.

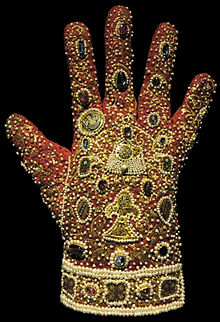

The Imperial Regalia of the Holy Roman Emperors, kept in the Schatzkammer (Vienna), contains a full set of outer garments made in the 12th century in essentially Byzantine style at the Byzantine-founded workshops in Palermo.

Court life "passed in a sort of ballet", with precise ceremonies prescribed for every occasion, to show that "Imperial power could be exercised in harmony and order", and "the Empire could thus reflect the motion of the Universe as it was made by the Creator", according to the Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus, who wrote a Book of Ceremonies describing in enormous detail the annual round of the Court.

At this period a court official could be required to wear five different outfits over a single festival day, his costumes being provided as part of his pay package.

[24] Various tactica, treatises on administrative structure, court protocol and precedence, give details of the costumes worn by different office-holders.

[25] As in the Versailles of Louis XIV, elaborate dress and court ritual probably were at least partly an attempt to smother and distract from political tensions.

This is certainly the area in which Byzantine and classic clothing is nearest to living on, as many forms of habit and vestments still in use (especially in the Eastern, but also in the Western churches) are closely related to their predecessors.

The bishop in the Ravenna mosaic wears a chasuble very close to what is regarded as the "modern" Western form of the 20th century, the garment having become much larger, and then contracted, in the meantime.

Modern Orthodox clerical hats are also survivals from the much larger and brightly coloured official headgear of the Byzantine civil service.

Men's hair was generally short and neat until the late Empire, and often is shown elegantly curled, probably artificially (picture at top).

The 9th century Khludov Psalter has Iconophile illuminations which vilify the last Iconoclast Patriarch, John the Grammarian, caricaturing him with untidy hair sticking straight out in all directions.

Although there were other important centres, the Imperial workshops led fashion and technical developments and their products were frequently used as diplomatic gifts to other rulers, as well as being distributed to favoured Byzantines.

This naturally stopped during the periods of Iconoclasm and with the exception of church vestments [3] for the most part figural scenes did not reappear afterwards, being replaced by patterns and animal designs.

Some examples show very large designs being used for clothing by the great - two enormous embroidered lions killing camels occupy the whole of the Coronation cloak of Roger II in Vienna, produced in Palermo about 1134 in the workshops the Byzantines had established there.

[4] A sermon by Saint Asterius of Amasia, from the end of the 5th century, gives details of imagery on the clothes of the rich (which he strongly condemns):[26]When, therefore, they dress themselves and appear in public, they look like pictured walls in the eyes of those that meet them.

On these garments are lions and leopards; bears and bulls and dogs; woods and rocks and hunters; and all attempts to imitate nature by painting....

But such rich men and women as are more pious, have gathered up the gospel history and turned it over to the weavers.... You may see the wedding of Galilee, and the water-pots; the paralytic carrying his bed on his shoulders; the blind man being healed with the clay; the woman with the bloody issue, taking hold of the border of the garment; the sinful woman falling at the feet of Jesus; Lazarus returning to life from the grave....Both Christian and pagan examples, mostly embroidered panels sewn into plainer cloth, have been preserved in the exceptional conditions of graves in Egypt, although mostly iconic portrait-style images rather than the narrative scenes Asterius describes in his diocese of Amasia in northern Anatolia.

Raw Silk yarn was initially imported from China, and the timing and place of the first weaving of it in the Near Eastern world is a matter of controversy, with Egypt, Persia, Syria and Constantinople all being proposed, for dates in the 4th and 5th centuries.

According to legend agents of Justinian I bribed two Buddhist monks from Khotan in about 552 to discover the secret of cultivating silk, although much continued to be imported from China.

Resist dyeing was common from the late Roman period for those outside the Court, and woodblock printing dates to at least the 6th century, and possibly earlier - again this would function as a cheaper alternative to the woven and embroidered materials of the rich.